Why women mistake a heart attack for anything else

Women often deny the heart attack signs and decide they’ve got indigestion or some other minor disorder instead of seeking treatment.

Every minute counts when you’re having a heart attack.

Getting to hospital, getting a rapid diagnosis and getting treatment is all about speed.

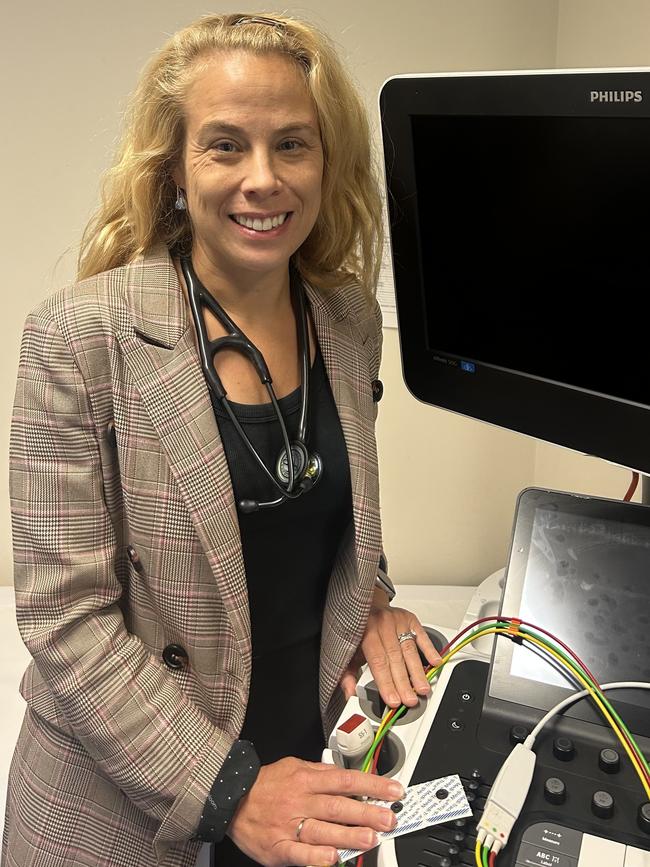

Which is why data that shows women on average take an hour longer than men to arrive at hospital after experiencing symptoms is a worry for people such as cardiologist Dr Clare Arnott.

Just as concerning is that it takes an extra 20 minutes on average for women to get to the “cath lab”– the coronary catheterisation lab – where doctors open up and clear clogged or narrowed arteries and perform other emergency treatments.

Arnott, a cardiologist and Pagent Director of Heart Lung Clincal Research at St Vincent’s Hospital, a staff specialist at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, and head of the cardiovascular program at the George Institute for Global Health, doesn’t offer a simple explanation of this gender gap.

It’s not as simple as “physician bias” with women being fobbed off as stressed or suffering reflux rather than suffering a heart event.

But Arnott is clear about the need for better messaging to women and clinicians about the high risks women face from what has traditionally been seen as a “men’s condition”.

“If you look at the number of men who will have a heart attack, versus the number of women, more men will have an attack in absolute numbers,” she says. “It’s not the case for all cardiovascular diseases (which includes strokes and blood vessel diseases) but it is for heart attacks. But if we take a step back, what’s really relevant is that cardiovascular disease is still the leading cause of death for both sexes.”

Arnott says women are often “walking around with high blood pressure and diabetes and obesity and elevated cholesterol” but are unaware of their heart risks.

“We’re very good at getting our Pap smears and we’re very good at getting our breast screens, but it’s not at the forefront of women’s minds to be thinking about their heart health,” she says. “There’s a bias in the community, from all of us as well, it’s not just a physician bias. Women tend to think CVD is not relevant to them.”

A recent survey of 90,000 Australian patients found women were 12 per cent less likely than men to have a heart check with their GP.

But Arnott says: “We have to be fair to GPs – they have such busy jobs and often have very little time to deal with the many health issues in their patients. But I hope, with education of all clinicians, we can put cardiovascular health at the front of mind for all clinicians when they see a woman as well as a man.”

Traditionally, doctors have believed the symptoms of heart attacks vary between the genders, with women presenting with anxiety; shortness of breath; upset stomach; shoulder, back or arm pain, and; unusual tiredness and weakness, along with the key pointer of chest pain. But Arnott says recent data does not completely support this idea of “atypical presentation”.

“What recent data supports is that women are just as likely as men to present with chest pain, but women are more likely to report additional symptoms,” she says. “So they might say, ‘I had chest pain’, but they’ll say ‘I’m also short of breath, or I feel a bit nauseous’, or they might add additional information. And I think that sometimes leads to clinician bias. If you’ve already got a bias in your mind, and a woman says, ‘I’ve got chest pain, but I’m also nauseous and I also had a bit of reflux’, then that bias kicks in, and someone says, ‘oh, this is probably just reflux’.”

But why do women report multiple symptoms?

“We don’t know,” Arnott says. “I don’t know if it’s because we have additional symptoms, or if it’s just about the way that women communicate, or that there’s female bias and we’re less likely to think it’s our heart.”

One problem is that cardiovascular conditions were in the past “massively underdiagnosed in women”, she says. “Historically, we’ve just really pushed a message that those at risk of heart disease are the middle-aged men.”

The role of caregiver may also be a factor in the relatively late arrival of women at hospital after an attack.

“I’ve had women say to me that they made the kids’ lunches and packed their husband off to work before they decided they better get to hospital,” Arnott says.

Medical protocols mandate that anyone presenting at emergency with chest pain must be given an electrocardiogram, ASAP. There is no Australian data but international data suggests it takes longer for women to have an ECG and that they are more likely to get a diagnosis other than a cardiac diagnosis – even when they’re having a cardiac event.

“That was a UK study which found that women presenting with a heart attack were more likely to have an initial incorrect diagnosis, and that it correlated directly with adverse outcomes and ultimately with mortality rates,” Arnott says.

She says cardiologists talk about “time is myocardium”; that is, any delay in treatment can translate to the loss of vital myorcadium, heart tissue. “The time taken to open that artery and restore blood flow is so important,” she says.

“What I say is, as a woman, never ignore chest, neck, arm pain or tightness. If you have chest, arm, jaw pain, irrespective of your additional symptoms, your number one thought should be, ‘am I having a heart attack?’.”

Arnott has a very personal cautionary tale to offer – via her stepmother, Lynne Arnott, an assistant librarian who lives about 55km out of Orange in western NSW.

Lynne, 61, took almost a week to seek medical help after she began to suffer what she thought was reflux, but turned out to be a seriously blocked artery. On a Thursday night last July, after sharing a roast dinner with her husband, Lynne started feeling chest pains, diagnosed it as indigestion and took an antacid tablet.

“It didn’t go away,” says Lynne. “So I took a couple more, and it just didn’t change. I kind of slept sitting up. If I was walking or standing or doing anything else, it wasn’t a problem. After three days of that, I started looking it up online and thought, okay, I’ve got to call a doctor. On Wednesday, it was still going on, and I still hadn’t called the doctor.”

Nor did she seek advice from her heart-expert stepdaughter, “because it never, ever crossed my mind that it was a heart attack”.

That morning, walking to the car for the trip into work at Orange, “I got the pain that I would previously get only while laying down”. Now Lynne knew she needed to see a doctor.

“Then I started getting pressure in my left arm, and it started radiating down to my wrist,” she recalls. “We were probably about half way to Orange, and my husband goes, ‘that’s it’. He pulled over, he sent Clare a text. She immediately called and said, go straight to emergency, don’t go anywhere else.”

In hospital, Lynne’s indigestion turned out to be a 90 per cent blockage of her LAD (left anterior descending) artery, which needed urgent stenting.

Lynne is on blood thinners for 12 months and will then take aspirin. She did an eight-week course of cardio-rehab doing education and physical fitness at the Orange Hospital and now makes sure she spends 15 minutes, six days a week, on an exercise bike.

“I’m not an expert, “ she says. “But I tell all my friends, ‘listen to your body if there’s an issue, let the experts tell you it’s not a heart attack’.”

Clare Arnott says women must also be aware of the additional risks that can be caused by pregnancy complications such as pre-eclampsia or gestational diabetes.

The lack of a uniform national screening program for cardiovascular conditions – for men or women – adds to the problem, and it’s one Arnott and colleagues at the UNSW and the University of Sydney have been working on since 2020.

The idea is to develop screening by “piggybacking” on mammogram tests.

“For a long time there has been data that suggests there are things in your mammogram that correlate with cardiovascular risk,” Arnott says. “We know the calcifications in the tiny arteries of the breast correlate with coronary plaque and cardiac events. But if you go and get a mammogram and there’s breast arterial calcification there, most of the time it won’t even be commented on. And if it is commented on, it will never be given any clinical relevance.”

The researchers have applied machine learning to routine mammograms to create an algorithm to detect cardiovascular “markers”, and are now doing qualitative work to test the possible uptake by breast mammography providers.

The Heart Foundation website says an Australian woman dies of heart disease almost every hour; that heart disease in women can occur at any age but the risk changes throughout life’s course; that women are less likely to attend cardiac rehabilitation, less likely to take their medicine regularly, and less likely to make heart-healthy lifestyle changes.

Arnott says the lack of medical research on women in general is also a problem. “From cells at the benchtop to patients at the bedside, women are vastly under-represented in medical research,” she says. “This means we lack understanding of pathophysiology as well as response to treatments in women.”

Dr Arnott’s key points

- Know your risk. Ask your GP to measure your blood pressure, cholesterol and sugars. Knowledge is power and we can treat these risk factors to reduce your risk of developing heart disease.

- Ask your GP what your cardiovascular risk is. Make sure you ask them if they have any female-specific risk factors. For example, previous pre-eclampsia or diabetes in pregnancy. These risks are often forgotten.

- Never ignore chest pain: always seek medical advice.

- Advocate for the women and men in your life: make sure they have a heart-health check too

- Visit the National Heart Foundation website. It has brilliant advice on living a healthy lifestyle, eating well and staying active. And it has specific advice on women’s heart disease.

Heart Foundation information

It’s important that people of all genders know the warning signs and symptoms of a heart attack, because early treatment is vital. The longer a blockage is left untreated, the more damage occurs.

The most common heart attack warning signs are:

- Chest discomfort or pain (angina). This can feel like uncomfortable pressure, aching, numbness, squeezing, fullness or pain in your chest. This discomfort can spread to your arms, neck, jaw or back. It can last for several minutes or come and go;

- Dizziness, light-headedness, feeling faint or feeling anxious;

- Nausea, indigestion, vomiting;

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing – with or without chest discomfort;

- Sweating or a cold sweat.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout