High BMI? It may not matter – a future blood test could deem you ‘healthy fat’

Scientists are developing a blood test to measure the risk of metabolic disease such as diabetes, heart problems or strokes, and it may be more reliable than the existing body mass index.

It’s the conundrum at the heart of using the body mass index (BMI) as a measure of health – some people who sport optimum measurements are metabolically unhealthy, while others in the overweight range are in perfect metabolic condition.

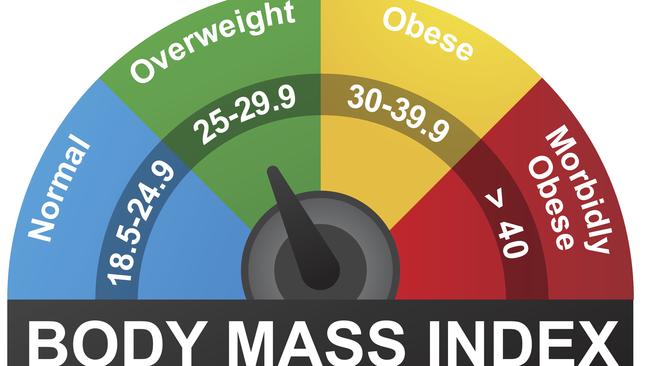

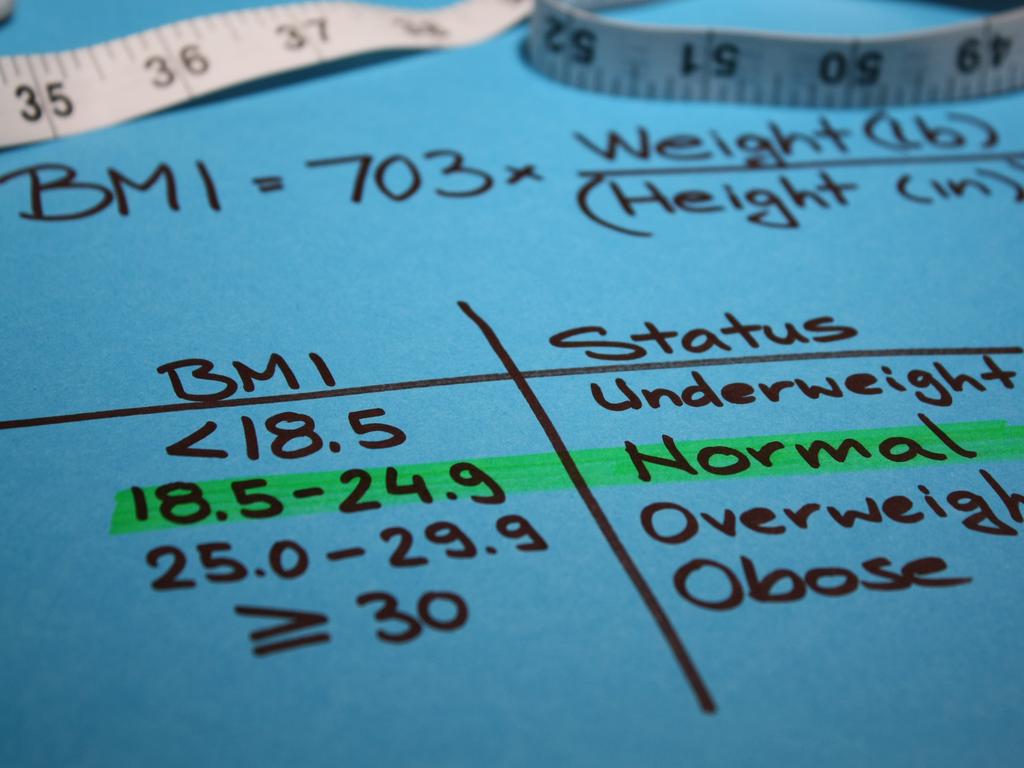

This paradox is demonstrated no more clearly than in the muscly athlete of superior fitness and extremely low body fat who measures up with a BMI of 30, which is the border between overweight and obese. A BMI is a person’s weight divided by height squared.

The vagaries of the BMI and increasing understanding of its limitations has also given rise to a notion of “healthy obesity” which has been embraced and promoted by the body positivity movement.

While this concept may be scientifically true for a minority of people, it’s a dangerous concept given the very extensive associations between obesity and chronic disease.

So how can you know, if you’re a string bean, whether you have been lulled into a false security and are in fact “skinny fat”, or if you’re overweight, whether you’re actually “fat healthy” and in excellent metabolic health?

Scientists from the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute are hoping that it won’t be long before you can find out the answer via a pathology test that would be readily available to everyone.

They’ve developed a method of measuring what is being dubbed “metabolic BMI” (mBMI) based on measurements of hundreds of lipids whose role in the development of obesity and Type 2 diabetes are becoming increasingly well understood.

Currently, standard health tests measure only LDL (“bad’’) and HDL (“good”) cholesterol and triglycerides. But a much more extensive lipid panel can put quite a different complexion on raw cholesterol readings and identify hidden risks of cardiometabolic diseases in people whose BMI and cholesterol number appear perfect.

“We know obesity is a risk factor for insulin resistance, diabetes, heart disease and liver disease but not everyone who is obese develops those different disease outcomes,” says Peter Meikle, Head of the Metabolomics laboratory at the Baker Institute.

“And so we have this concept that’s been around for a while of healthy obesity. I’m not advocating that because I think eventually, even though your metabolism may be normal when you first become obese, eventually you are probably going to develop an unhealthy metabolism.

“But at the same time you have lean people who think they’re healthy because their BMI is 22 or 23, but their metabolism is dysregulated, so they are at risk of the development of metabolic diseases. The point is you just can’t see this from looking at someone’s physical appearance or just measuring BMI.”

Professor Meikle and Dr Habtamu B Beyene are two of the authors of a new paper that reported the results of a mBMI model that tested 575 lipid species alongside age and sex data, finding that the results explained over 60 per cent of the differences in individuals’ BMI, thus demonstrating that dysregulation of lipid metabolism is tightly associated with obesity.

Some of the most important classes of lipids included as part of the test are plasmalogens, which are associated with oxidative stress and inflammation, and ceramides, which are involved in cell signalling and can also lead to an inflammatory state in the body. Inflammatory processes in the body are significantly associated with obesity.

The Nature paper found that despite having comparable BMIs, people with metabolic BMIs substantially higher than their actual BMI presented with a “deleterious metabolic profile” compared with participants with an mBMI substantially less than their actual BMI.

The team also found that the odds of being diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes was more than fourfold higher in those with the worst results for mBMI compared to those with the best results.

The paper notes this finding was consistent with previous studies that have found people with overestimated BMIs based on their metabolism had lower triglycerides (which is good) and lower levels of bad cholesterol.

“Cholesterol is a very useful biomarker, we’ve used it for a long time and it does predict heart disease risk very well but it’s still a relatively blunt measure, and it doesn’t reflect all of the complexity of our metabolism,” Professor Meikle said.

“Technology has now moved on and it’s possible to measure these many hundreds of different lipid species and that gives us a more refined picture.”

Baker Institute scientists are working with the company Trajan Scientific and Medical to develop a point-of-care test that would mean people would be able to simply obtain a reading of their metabolic BMI. Primarily the aim would be to identify “skinny fat” people who may be at heightened risk of metabolic disease but have little idea that was the case.

“If people have the ability to measure their metabolic BMI themselves by simply taking a fingerprint bloodspot and sending it through the post to be tested, it allows people to take more control of their own health and more responsibility for their own health,” Professor Meikle said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout