Cryogenics? No thanks, I’d get brain freeze

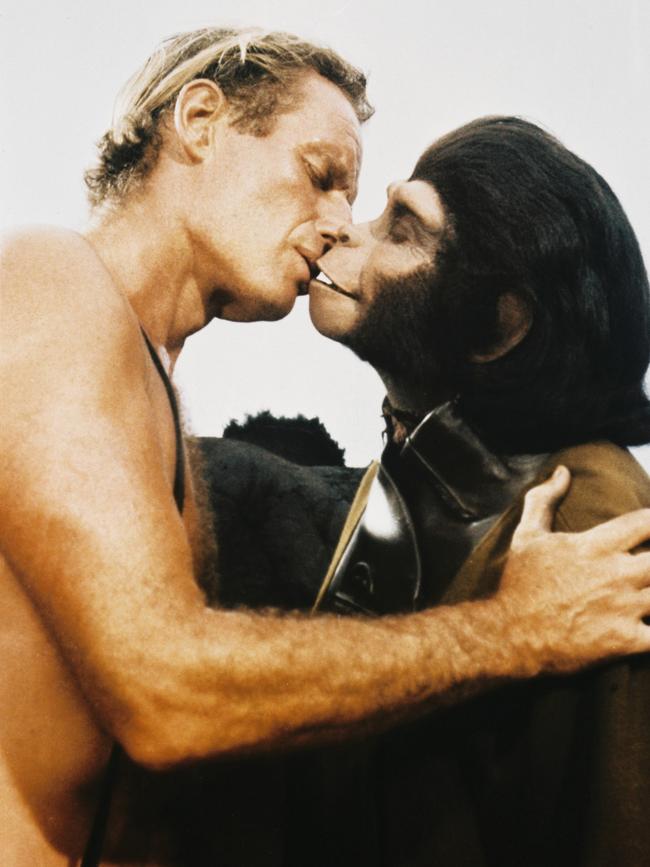

Who knows where you might end up if you opt for future freezing. Planet of The Apes anyone?

A great friend recently underwent a 14-hour operation for an extremely serious health issue, but before the scalpels went to work we shot the breeze about the notion of living forever.

More specifically, we pondered the notion of cryogenics, or freezing the body and storing it until science and technology worked out how to conquer death and reanimate our weary old bodies in the future.

I didn’t like the idea. I was particularly prone to ice cream brain freeze and didn’t think being totally snap frozen would suit me.

He was open to the entire notion. It’d be like time travel, he theorised. Who knows what sort of world we might wake up into? Maybe his impending epic surgery might be as easy as clipping a toenail in the future.

I told him it wouldn’t be a lot of fun if the apes had taken over and our new reinvigorated selves spent our whole time running through cornfields – a la Charlton Heston in the original Planet of the Apes – being chased by leather-jacketed, rifle-wielding silverbacks.

That’s nothing, my friend argued. Cranky old Charlton was mucking about in the year 3978. Take The Time Machine by H.G. Wells. That time traveller landed in the year 802,710.

It wasn’t much fun for him, from what I remember, I said. He arrived on a planet full of sack-wearing, fruit-eating halfwits. Then he went millions of years into the future and there was nothing there but vicious human-eating crabs and a black blob with strange tentacles. What if we reach the point where we’re supposed to be thawed out and the people of that time can’t even count?

Time travel is a gamble, my friend, he said.

It all sounded like a load of sci-fi twaddle, I reasoned. But recent developments in the world of human deep-freezing suggest there are enough people who think it’s a viable concern.

In 2021, in the midst of the global pandemic, The New York Times reported a spike in global interest in cryonics.

“Supporters of cryonics insist that death is a process of deterioration rather than simply the moment when the heart stops, and that rapid intervention can act as a ‘freeze-frame’ on life, allowing super-chilled preservation to serve as an ambulance to the future,” it wrote.

“They usually concede there is no guarantee that future science will ever be able to repair and reanimate the body but even a long shot, they argue, is better than the odds of revival – zero – if the body is turned to dust or ashes. If you are starting out dead, they say, you have nothing to lose.

“During the pandemic, a heightened awareness of mortality seems to have led to more interest in signing up for cryopreservation procedures.”

Last year an Australian outfit, Southern Cryonics – the only “cryopreservation” facility in the southern hemisphere – announced it had installed its first preserved patient in its headquarters in the small NSW town of Holbrook near Wagga Wagga, about 490km southwest of Sydney.

Holbrook was home to at least a portion of the HMAS Otway submarine. The town itself was named after Lieutenant (later Commander) Norman Holbrook, a World War I submarine captain who won the Victoria Cross for valour.

Now it had a cryogenics warehouse.

Patient 1 passed away in Sydney.

Southern Cryonics said: “The patient was securely wrapped in a special sleeping bag that stays intact in liquid nitrogen. Patient 1 was then cooled to dry ice temperature and transported to our Holbrook facility. At the facility, Patient 1 was gradually brought to liquid nitrogen temperatures in Southern Cryonics’ computer-controlled cooling chamber and then transferred to a Dewar (a specialised storage flask).”

It might all sound like a bit of a gamble, as my friend attested, but what if it paid off? If it did, then Patient 1 and all the Dewar-dwellers around the world would have the last laugh. And the naysayers? They’d all be dust anyway.

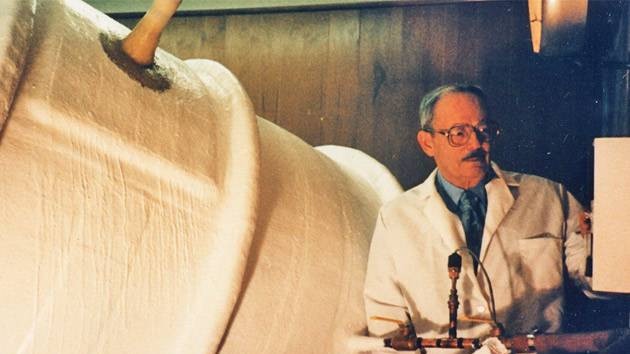

Forget about H.G. Wells and Cranky Charlton, modern cryogenics began with American war veteran and academic Robert Ettinger and his book The Prospect of Immortality, published in the early 1960s.

As he wrote in the opening chapter of that book: “Most of us now living have a chance for personal, physical immortality. The remarkable proposition … is easily understood by joining one established fact to one reasonable assumption.”

The fact was that it was possible to store a human body “indefinitely” at low temperatures. If civilisation endured, the book contended, medical science would “eventually” be able to repair damage to the human body including “freezing damage and senile debility”.

Thus an entire industry was born and continues to grow.

In the early 2000s, the New Yorker magazine published a feature story on US architect and cryogenics advocate Stephen Valentine, who hooked up with a group called the Life Extension Foundation and conceived of a building called the Timeship – a multipurpose structure potentially containing thousands of cryogenically preserved humans that would operate seamlessly and without interruptions from the outside world for a century.

“There are so many complications,” Valentine, reflecting on his Timeship, told the magazine. “The whole science level – how do you make this work? Have a column whose top is at room temperature and whose base is at absolute zero? The life-support systems, the security systems, the difficulty of making all of that part of a building that is inspirational. There are so many levels, really: spiritual, philosophical, ethical, love, life, and death.”

I wanted to know what happened to Valentine and his wondrous Timeship in the past quarter-century. Were hundreds, thousands, of hopeful Americans in his deep freeze waiting for a brighter future?

It was reported that Valentine had found the perfect location – no earthquakes, avalanches, volcanoes, hurricanes, sinkholes, lightning strikes, rogue glaciers, and showers of meteors etc. – in the little township of Comfort, Texas.

Was this icy community receiving comfort in Comfort?

I found a website for the Timeship which said “website under construction”.

And some information: “In June 2019, the Timeship project moved its operations from Comfort, Texas to New York City. An exhibit of Timeship will be forthcoming at a prominent museum, 2025-26.”

Hmm. I guess the world of cryogenics sometimes moves at a – ahem – glacial pace.

Still, my dear friend who underwent his mammoth operation – it was a complete success – remained interested.

We plan to have a drink to celebrate his future good health.

Me a Sans Bar Kings of Tartan Whiskey substitute, neat.

And he a full-blown Johnny Walker. With ice.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout