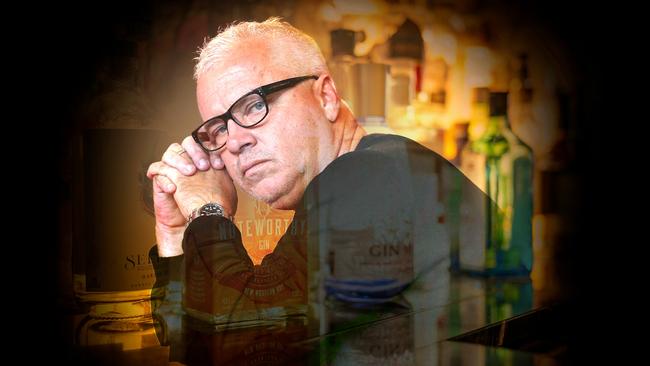

The year of magical non-drinking

One year on from an alcohol-fuelled haze last New Year’s Eve when Matt Condon vowed off ever drinking again, this is how it’s worked out.

“I feel bad for people who don’t drink. When they wake up in the morning, that’s as good as they’re going to feel all day.” Frank Sinatra

Each year at the end of summer my wonderful neighbour, here in the wilds of the NSW Northern Rivers, hosts a wine tasting night.

No, let’s give it the honour it deserves – a Wine Tasting Night.

The event is held on his back veranda with views of rolling paddocks and an ancient line of towering camphor laurels.

My neighbour’s Wine Tasting Night has, over the years, become famous, in an underground, nose-tapping, wink-winking, those-in-the-know sort of way. Put it like this. There is Christmas Day. There’s Easter. There are birthdays, anniversaries and respective festive days celebrating mothers and fathers.

Then, if you’re lucky enough to be invited, there’s my neighbour’s Wine Tasting Night.

Friends jet in from the other side of the country for this singular evening. Other invited pilgrims wander in from the length and breadth of Australia’s East Coast. They come in a sort of zombie state, dribbling at the recollection of the previous year’s ambrosia and doubly dribbling in anticipation of the new year’s offering.

It’s an interesting crowd, given my neighbour used to be a high-ranking NSW police officer who had had more life-threatening encounters with the Sydney underworld than you or I have had tumblers of warm Yellow Tail Chardonnay at the tail end of a long, boozy dinner party when anything alcoholic will do.

But on Wine Tasting Night, tales of derring-do and old crooks pale compared to my neighbour’s knowledge of wine, and the stories he attaches to innumerable vintages over the decades.

The evening goes like this.

My neighbour, the wine ringmaster, will bring out a particular bottle and everyone at the table is given a thimbleful in a tasting glass. They swill, sip, swallow, then come up with a rating from 10 to 1 (10 being the highest score), which is then recorded on a score sheet.

The judging spreads across eight or nine different types of wines of varying ages.

Then the evening’s Grand Winner is selected.

It is, in short, a celebration of alcohol. A genuflection to the history and craft and care behind one of life’s great pleasures.

There were more than 20 people supping at my neighbour’s splendid Wine Tasting Night 2024.

And how they enjoyed the 1984 Morris of Rutherglen Tawny Port (bottled when I was just 22 years old and enjoying humble tap beer, mainly XXXX, at hotels in inner-western Brisbane). The 1977 Dow’s Vintage Port from Portugal (when my strongest beverage was a Milo milk). And the 1956 Penfolds Vintage Tawny Port (several years before I was a twinkle in my parents’ eye.)

Everyone imbibed.

Except one.

Everyone laughed and quipped and judged and some even danced between wines.

Everybody but me.

Why? Because I had made a new year’s resolution just a couple of months earlier, one of dozens down the years that had been declared and just as quickly abandoned, and somehow had clung by my fingernails to the raft of this one and stayed true.

That resolution was to give up alcohol.

Like most New Year’s Eve resolutions, mine was made on New Year’s Eve, after several beers, some glasses of wine and a splash of champagne. Resolutions about giving up alcohol that are actually fuelled by alcohol have a habit of quickly cancelling themselves out.

Still, there I was, sitting in the glow of party lights on my neighbour’s back deck, surrounded by people who suddenly all seemed to be wearing red lipstick, men and women alike, courtesy of the ports and their elderly tannins, and whose laughter grew louder, their eyes wilder, their wit saucier.

The Grand Winner was announced and there was much concurring and discussion and warm merriment that only comes in the wake of tasting something in life you know you may never encounter again, and already your memory of it is forming.

I felt like a little boy in shorts, long socks and sandals (and with a demonstrable cowlick), forgotten by the grown-ups and left in the corner.

I stared into my glass of soda water, with its furry lemon rind, and asked myself – what have I done?

My family history didn’t contain, as far as I knew, any raging alcoholics despite our Irish lineage.

There was a great-uncle who may have been a heavy imbiber. There were stories leaked down the years that hinted at his wild, sometimes uncontrollable behaviour, his temper tantrums and legendary parties in the 1950s that went on for days.

So he was either a serious boozer or, as has been hinted, was a sandwich or two short of a full picnic.

Growing up there was little alcohol in our house. I remember as a child my mother drinking sparingly – a Bacardi and coke back in the 1960s and early 1970s – before she stopped altogether soon after that for reasons unknown. And Dad enjoyed the occasional Scotch whisky and little else. To this day he has a single ritual Scotch in time for the evening television news.

My childhood liquor cabinet was bare. In fact, we didn’t even have a cabinet.

Later, in a new house, and as was the custom in that era of brick Spanish-style suburban monstrosities, my parents had a pool room and at the end of it a small brown-brick bar. And on the wall behind the bar was a large, framed poster with the word CARLTON in bold across the top and featuring a bearded man, himself standing at a bar, and at the bottom was written: “I Allus have Wan at Eleven”.

I used to ponder at length those strange words, a sort of cryptic Aussie strine that apparently only emerged after several pints of lager. Years later I found the complete version of that little ditty: “I allus have wan at eleven/ it’s a habit wot’s gotta be done/ Cos if I don’t have one at eleven/I allus have eleven at one.”

From my mid-teens, Dad would allow me a bourbon or two on New Year’s Eve, and they would tip me into a sudden silliness that I can only compare to the temporary “zoomies” our pet dogs seem to regularly suffer from most days.

Even during my university years in Brisbane where I lived on campus in an all-male college that had a “reputation” for wild behaviour, I encountered alcohol in relative moderation maybe once a week. The “dances” with the all-female college next door were different.

There, my “zoomies” stretched into the early hours and came with my first experience of the adult “hangover”. And it may have been this, the brutality of the first true hangover, that made me gun-shy of alcohol.

I finally understood that drinking, this incredibly pleasurable pastime, came with a price. A sting in the tail. A consequence.

Nobody was experienced, or wise, enough at that stage to tell you that the power of alcohol was so great that it could, and eventually would, ride roughshod over the downsides of a trifling hangover. That alcohol had the ability to eat the tail of its own destructive qualities, and spin ceaselessly into infinity. Like the heads of young, inexperienced drinkers. Like my young head.

Nobody told you that.

And you certainly weren’t warned when you decided to join the noble ranks of journalism that just as the survival of a goldfish is contingent on it having a tank of water to live in, so a job in the media seemed hugely reliant on an accompanying vat of booze.

The cliches of journalism and drinking are boundless.

There were certainly older members of the newspaper staff, when I was a cadet, who immediately posed a question, a chicken and egg conundrum the answer to which continues to remain elusive.

Did journalists become heavy drinkers because of the job? Or did they gravitate to the job because it facilitated their drinking?

No matter. The vast majority of my colleagues were so high functioning after a drink that you wondered if they had some common metabolic make-up, a gene that permitted them to not only work after what we once called “a skinful”, but in fact to raise their acumen from its sober level.

This, to my impressionable mind, was something of a miracle.

Perhaps it was as simple as a matter of developing a level of tolerance above and beyond other professions. One Sydney newspaper colleague, in fact, possessed a constitution that was at first humorous, then terrifying.

The more we all drank, our inhibitions loosening, the talk a little blurred at the edges, the more sober he appeared. Litres of beer coursed through him and left him unscathed. “He’s from out bush,” we rationalised. Which he was; a solid, thoroughly decent young man who’d come in from a farm in western NSW to ply the journalistic trade in big, bad Sydney.

He was the type of soldier you’d want beside you going over the trenches.

But for the majority of us, our drinking was of the weekend binge variety. Yes, terrible lapses in judgment were made. Serious injury narrowly avoided. Catastrophes averted. And we lived to write another day.

We didn’t know then, however, the more dangerous shoals of a relationship with alcohol lay ahead.

Who would have thought that having survived the storms that alcohol-fuelled behaviour threw in our paths in the outside world of pubs and clubs, that the greater perils lay within?

As many of us followed the largely predictable paths of marriage and children, tethered to home, no longer whirling free agents limping home at dawn. As the great noir novelist Raymond Chandler wrote: “I’m an occasional drinker, the kind of guy who goes out for a beer and wakes up in Singapore with a full beard.”

At some point that state of mind, of being, disappeared, quietly and literally replaced by one of the heaviest words in the language – responsibility.

With the advent of responsibility, things once essential to life quietly disappeared: Friday night pool with the lads in the local pub; invitations to parties (not quaint birthday celebrations in civilised restaurants, but raucous party parties where a hundred people crammed into a studio apartment and the booze was chilled with ice in a bathtub and the music was so loud every conversation was someone screaming a question and you just nodding and saying “Yeah”, and where there was a distinct possibility you’d end up sleeping the night beneath a hedge in the back garden) and the offer of “a few quiet ones” in the local at midday on a Saturday that devolved into an odyssey, the wheels only falling off the wobbly cart the next day.

Partners and children meant your life, to a degree, turned inward.

All the pubs and clubs and bars and restaurants and dance halls and saloons and beer barns and cocktail nooks disappeared, reduced to a strange, coagulated version of themselves, now all located under one roof in your home. And that home was called Responsibility.

So began a gentle glass of wine at the end of the day that somehow helped lighten the relentless load of responsibility. That “took the edge off” the day. Then that became two glasses. Then three. Then a beer before the wine parade, just to mix things up.

You never worried about drink driving because you never went out. When you did, you were struck by the utterly peculiar situation you found yourself in. What is this? What are all those lights? Who are those creatures milling in the shadows? It’s called nighttime.

Until one New Year’s Day you woke up nursing yet another annual resolution.

I’m giving up the grog. Really. Truly.

And you began the crawl back through the years, then the decades, back through the ache of responsibility and the party years and the work routines and the university frolics and the tentative first sips of a Jack Daniels and coke on ice in the distant country of your teenage years, back, back to the day before this thing called alcohol ever touched your lips.

The first day of a grand resolution is the easiest because in those initial hours you’re so self-important about your decision that you’ve deceived yourself into thinking you’ve already done the heavy lifting.

What decision could be greater than vowing to abstain from alcohol?

You believe, in the flush of the resolution, that you’ve already lived the decision, were months, no years, into sobriety having traversed a difficult path now littered with fresh daisies, the sky blue, your ears ringing with the congratulations of everyone you ever knew.

Here I am, a person who has given up alcohol once and for all. Hooray for me.

By early afternoon of that first day you’re telling yourself you can already feel the health benefits. How good is this? By late afternoon you’re on the phone trying to convert family and friends to the life-altering benefits and transcendent glories of being sober.

Then at nightfall, a distant bell rings in the back of your head, and you know that bell is being rung by somebody called Ivan Pavlov.

Gone is the bravado about clean living and shunning the devil drink. Forgotten is the sound of your confident footsteps on the yellow brick road. The large ropes that were holding down your resolution are already beginning to chafe and fray.

For years the early evening meant feed the family, feed the dogs and feed yourself a glass of beer or a goblet of chilled chardonnay or chablis or anything that was white and inside a wine-shaped bottle in the fridge.

You’d heard somewhere that between 6pm and 7pm was the critical ridge to get across in the world of sobriety.

But in this new, clean world, it hits 6pm and you don’t know what to do with yourself. Your right hand reflexively raises itself, the elbow crooked, but you’re grasping thin air, not a glass stem.

You’ve entered Heartbreak Ridge. The shadows are long. Everything seems to be standing still. The dogs stare at you, puzzled.

Just 24 hours earlier you were playing YouTube Jukebox on the television, full of soup and nostalgia. YouTube Jukebox involved you trawling through old music clips. Wailing at the top of your lungs to REO Speedwagon and Cheap Trick and Blondie. Or misting over at the ballads of Shania Twain and A-Ha.

But on the inaugural night of the resolution there is nothing but the metronomic sound of the plastic Chinese-made Lucky Cat ornament on the sideboard and the guttural call of a green frog on the back deck.

Cats and frogs.

Where was the fun in that? This was my first thought as I crawled across the broken glass of Heartbreak Ridge as the clock approached 7pm on that inaugural night. Without the little six o’clock swill, life had suddenly been drained of colour.

Don’t just stand there. Read a book, my wife said. Go for a walk. Do the crossword. Watch some cricket on the television. Do something.

It stretched out, that night. Not exactly a night of long knives, but a vacuum of a night, a night of minor grieving, the vacuum soon filled with self-pity and internal debate. What’s a little glass of wine, anyway? How bad could it be? Who cares? Why am I punishing myself? Life’s to be lived, right? So what if giving up the booze adds a few years onto your life? Is the old and decrepit end really the one you want years added to anyway? Poor me.

I remembered the story of a journalist friend of mine who told me that his own father, when he was 30, decided to give up smoking. Then when he was 80, the old man took it up again.

“So Dad,” my friend said. “How does it feel?”

He said his father slowly closed his eyes with extreme pleasure after a puff and replied: “Bloody marvellous.”

Still, I breached the ridge on that first night. Slept. Woke.

The resolution went from just words to serious business.

Just yesterday I’d told virtually everyone I knew that I was on this new mission. Now I felt accountable. I’d dug an accountability hole for myself. I had lost all of my proselytising fervour. Now people would ask me how the resolution was going. How was I feeling? Any different?

By day two I knew I needed something to get me through. To assist me across the bridge from daily drinker to stone cold sobriety. This resolution revolution, I suddenly knew, was not going to be easy.

I needed a placebo.

And that’s when I wandered into the world of non-alcoholic drinks. In particular, zero-alcohol beer.

A close mate had briefly inhabited this world. He gave me some tips. What to consider. What to avoid.

“Forget zero-alcohol wine,” he warned me. “Fake wine has a long way to go. But beer. That’s a different story. It’s almost there.”

Almost where? An accurate replicant of the real thing, just without the zoomies and the fun? Again I was a stranger in a strange land. A pilgrim. With a wooden staff. Wandering the deserts of non-alcoholic beverages convinced that fakies would always be fakies. That there was too much fakery in the world. We were saturated with fakeness. Life was too short to be satisfied with knock-offs.

But I was a parched pilgrim, and I desperately needed that bridge. That holy grail that would trick me into thinking I was off the wagon when I was still bumpily riding atop it (or on the wagon and bumpily riding off it. Whichever one it was. I could never remember).

So I put my head down and hunted for that grail. I did my research. I taste-tested. I swished it around in my mouth and across my sceptical palate like some lederhosen-wearing brewing judge at an international beer competition in Baden-Baden.

Then unbelievably the thirsty pilgrim found it. I found the bridge. Or more accurately I found cartons of one specific fake beer that I just might be able to stack into a bridge. Rickety, yes, but a bridge nonetheless.

And with the sort of addictive drive that had got me hooked onto real beer and wine in the first place, I cornered the market of this particular brand of fake beer. I criss-crossed the region snaffling every case I could. I raided liquor barns. Pillaged bottle shops.

At 6pm, at the start of the Heartbreak Ridge hour, I sat and cracked a can and sipped and closed my eyes and for a second, just a second, with its delicious hoppy aftertaste, its froth, its fizz, I could have been back on a bar stool in the London Hotel in Balmain, Sydney, an old haunt, two decades before, blowing the top off of a cold one before I was kidnapped by Responsibility. Or on the back deck of my Brisbane rental as a young cadet journalist with my old mate Dave, chugging a brew beneath the arms of a giant poinciana tree.

Or in this exact spot on the lounge chair just days ago, singing madly to Just Keep Walking by INXS. “Broken bottles, bricks and dirt … fast car driving, sleek and modern … shove it brother, just keep walking.”

So I kept walking with my resolution.

A week became a month. One month, two. Then six. Then 12. One whole year without a drop of booze. Probably the first such year since I was 15.

I once would have said – I’ll drink to that. But I won’t. Because I can’t.

The most accurate way to describe my year of sobriety was that it was eerily similar to a game of Snakes and Ladders.

Some argue this simple game – out of ancient India – is a metaphor for life. Life’s journey, the progression up the ladder, is fraught with peril and vices (the snake).

As the months of non-alcohol accrued, I kept a careful eye out for the snakes. I avoided social events. I paid attention to any past drinking triggers, like big sporting events. It took many months to feel comfortable in a restaurant, surrounded by walls of illuminated booze, even the nearby music of wine being poured into a customer’s glass.

I was vigilant about the snakes – when you actually have to start looking for them you realise they are literally everywhere – because I knew if I made a single slip, if I even had one sip of alcohol, that I would slide back to the beginning of this journey, that I would return to Day One of my resolution, and that all of that incredibly hard work, that effort and will, would go out the window.

This is what has kept me off the grog, more than the health benefits or the money savings (they are substantial) or the fact that I’m much more present in the world. I simply couldn’t face throwing all that physical and mental effort out the window for the sake of a schooner. I had come too far.

Has it been worth it?

The quality of sleep is so rich and alluring that even the prospect of it has become a small nightly pleasure. Some niggling ailments have disappeared. The energy levels are right up there, like a recharged battery. Some weight has been shed.

Make no mistake. There are moments when I pass a bottle shop, or go to a pub with a mate and find myself inside that rich bouquet of booze and wet bar towels, or spot happy people on a picnic blanket toasting with champagne flutes, and see thousands of sporting fans on telly laughing and carousing while they clutch big plastic mugs of beer and I think – wouldn’t it be nice?

Sometimes, in the evening, at a time when I was once pleasantly buzzed and wondering how much wine was left in the bottle in the fridge, I’ll text a mate and write, apropos of nothing – 300 days without a drink, but who’s counting? Crying emoji.

I have no need any longer for the fake zero-alcohol beer bridge.

And booze feels like an old friend I lost touch with a long time ago.

Now, without wishing to sound too airy fairy, there are flashes of feeling and insight – on a morning walk by the sea, or at the beach with family, or admiring a city skyline with the orange dawn coming alive behind it, seeing everything so clearly and in such granular detail, your lungs filled with fresh air – that repeat the same things.

One is a sense of gratitude.

The other? Life can be, and is, wonderful.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout