How the standard drink was defined, and why some people ignore it

You think you’re imbibing wisely. But are the alcohol guidelines reliable?

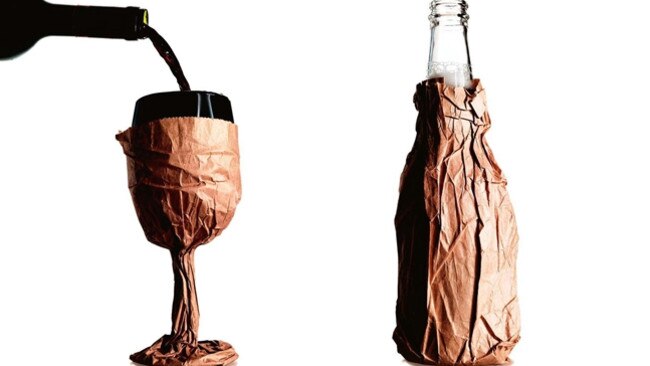

You’re at a social event: a party or in a bar. The booze is flowing but you’re being good. You think you’re au fait with the government advice on low-risk drinking: two units a day, no more than four at any one time. You’re not driving, so you can have four units and as you’re a wine drinker, that means you’ll have four glasses of vino, then stick to water. Congratulations.

Except … those four glasses of wine have been quite large, haven’t they? About 150ml, the norm for restaurants and bars here. And it’s shiraz you’ve been drinking — about 14 per cent alcohol. Sorry, but according to the Australian guidelines — which define a unit as 100ml of wine at 11.5-13.5 per cent alcohol — you’ve probably consumed about six units or even a bit more, which makes you a binge drinker. Officially, you may be of harm to yourself and others. If you’re drinking like this regularly, your risk of cancer has also increased quite markedly, perhaps even doubled.

But wait. Wildly different guidelines around the world mean that if you’re on holiday in Chile, daily consumption of nearly six units is still considered low risk. So well done, you’re within the limits. But in Grenada, more than one unit a day is ill-advised. Oh dear, I’d join AA and start researching cancer treatments now if I were you. Confused?

We’ve had alcohol guidelines for nearly 30 years, ever since the first advice was drawn up in London by the Royal College of Physicians in 1987. But how valuable are these baffling protocols? Doctors and experts agree that the unit system is difficult to understand and can’t be realistically applied to our lifestyle, when servings in restaurants and bars are usually larger than average, and when the effects of alcohol vary according to our size and metabolism.

Nor is there any international consensus on the science; the protocols vary widely across the world. A 2013 study by the University of Sussex, which looked at government advice on drinking in 57 countries, found almost no consensus about what constitutes harmful or excessive alcohol consumption on a daily and weekly basis. A 2016 study by Stanford University found only 37 of the world’s 75 more advanced countries had official protocols at all. So can you blame anyone for leaving the guidelines at home when they go out?

The Royal College of Physicians, an imposing building on the fringes of Regent’s Park, London, has for centuries been a centre for pioneering medical research. Its 1987 report wasn’t the first time the RCP had drawn public attention to the harm caused by alcohol abuse. In 1726 it made a submission to the House of Commons on what it described as a “great and growing evil”. But in the mid-1980s, doctors were becoming alarmed at the growing number of people they were seeing who had been damaged by alcohol. At the time, a study of medical outpatients showed that up to one-fifth were drinking 10 units of alcohol a day. The problem was regarded as so great that the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of General Practitioners had also prepared reports to express their concerns.

The Royal College of Physicians put together a working committee of epidemiologists, cardiologists, neurologists and endocrinologists. Their subsequent report, entitled A Great and Growing Evil: The Medical Consequences of Alcohol Abuse, found that a number of medical problems — including liver disease, stroke, heart disease, brain disease and infertility — were associated with excessive drinking. But what made it historic was the advice the committee drew up for low-risk drinking. In the first ever guidelines for alcohol consumption, the report advised that men could drink 21 units a week with little risk of harm, while women could drink 14 a week. Drinking up to 50 units a week (for men) and 35 units (women) was hazardous, while consuming more than this was positively harmful. The committee advised that one unit of alcohol was measured as half a pint of beer, a standard glass of wine (of eight to 10 per cent alcohol) or one measure of spirits (32 per cent alcohol).

The report was the most significant study into alcohol-related disorders to date and its advice has been the base on which drinking guidelines in the UK and Australasia have been measured since. But on what scientific evidence were the guidelines based?

“There was no science behind our advice. We pulled the guidelines out of the air,” Dr Richard Smith tells me over the phone from London. Smith, a former editor of the British Medical Journal, was a member of the RCP’s working committee in 1987 and a key adviser on the alcohol guidelines. But, as he tells me, the advice that became the blueprint for 30 years of guidelines could not come from any scientific base because there was no science available at the time.

“I remember it all rather vividly,” he says. “There were about a dozen of us on the committee and one day we were sitting around the table and someone said we have to come up with safe limits. The epidemiologist, David Barker, said, ‘That’s very hard, we don’t have reliable data, we can’t do this on scientific grounds’. But epidemiologists don’t see patients. Most of the rest of the committee did and we knew that patients would ask us, ‘How much should I drink?’ What do you do? Do you say to them, ‘I have no idea, come back in 20 years and we will have something?’ So we just went, ‘Well, three drinks a day sounds about right for men, and women should drink a bit less so let’s say two drinks for them; so that’s 21 units a week for men and 14 for women. And that’s how it happened.”

At the time the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of General Practitioners had also done a report on safe alcohol consumption. “We realised that it wouldn’t be good if we all came up with different guidelines so there was a behind-the-scenes fix to come up with the same levels,” Smith says. “It wasn’t a completely unreasonable thing to do. If you accept the argument that you have to keep to safe levels, you have to offer some guidance. We felt it was better to offer people some advice rather than no advice.”

I’m in a Sydney bar with a group of people aged from late 20s to late 40s. The designated drivers are sticking to two drinks (note drinks, not units) but no one else is taking much notice of how much they’re drinking. One 27-year-old in particular keeps holding her glass up for more wine with the often-heard refrain: “I’m not driving.” They’re all aware, more or less, of the alcohol guidelines; some think the daily limit is three, others get it right at two but no one is counting the units; to be honest, no one really cares. Most say they try not to drink Monday to Friday but the weekend is for fun. When I try to explain the complications of units versus size of drink, their eyes glaze over. “We’re here to have a good time, not to do arithmetic,” says the 27-year-old.

Regardless of the maths, the problems, both health and social, caused by alcohol continue to rise. At first glance the statistics don’t seem too bad: the overall consumption of alcohol in Australia is at its lowest in 50 years. But nearly a fifth of us still exceed the lifetime risk guidelines while a quarter of us binge drink at least once a month. Figures from the National Health and Medical Research Council show that 32 per cent of men in their 40s and late 20s were likely to drink at risky levels while 15.6 per cent of people have consumed 11 or more standard drinks on a single drinking occasion in the past 12 months. A 2014 study commissioned by Victoria Health found that up to 15 people died and more than 430 were admitted to hospital every day due to alcohol-related illnesses.

It doesn’t help that the information about alcohol and health is confusing and contradictory. How many reports have you read about red wine protecting against heart disease? Other studies indicate alcohol is a factor in heart disease while still others say red wine is only protective in women aged over 55.

Australia introduced guidelines in 1987, which suggested four units a day for men and two for women, but these seemed to be drawn up by a method similar to the first UK effort. They have been revised a number of times since. Professor David Hawks, one of the authors of the Australian protocols, wrote two years later of the enormous complexities involved in trying to advise on safe drinking levels but said, as Smith had, that some advice was better than none.

Professor Robin Room, of the University of Melbourne, who has studied international guidelines, told me: “I wasn’t involved in the 1987 guidelines but I would say they didn’t have any particular basis for where they would draw the line.” In a report on Australia’s updated guidelines in 2009, Room and a colleague found: “In this circumstance, committees seem to have drawn a deep collective breath and simply voted for specific cut-off levels.” Room tells me: “We’re saying it’s arbitrary, but not in the sense that they were scratching their heads and saying, ‘What do we think?’”

Some experts now believe there is no safe level of drinking: Sir Ian Gilmore, a liver specialist and former president of the Royal College of Physicians, and a key adviser for the UK’s most recent guidelines, believes it is misleading to tell people that there is any quantity of alcohol that would do no harm. “Alcohol is classified by the World Health Organisation as a class 1 carcinogen,” Gilmore has said. “You can’t say it is safe.”

The issue, then, isn’t whether alcohol is a major health risk. It is, and we’re only now beginning to understand how great a danger to our health it might be. The issue is whether we can trust our current guidelines to give us an accurate estimate of how much we should be drinking: are they evidence-based or still drawn just from intelligent guesswork?

In its introduction to the guidelines, the National Health and Medical Research Council admitted: “The advice in the guidelines cannot be ascribed levels of evidence ratings as occurs with other NHMRC guidelines … The guidelines identify limitations in our understanding and controversy in the evidence.” Asked what evidence they based their guidelines on, a spokesman replied by email: “Rigorous, transparent and internationally recognised approaches are used to ensure that all NHMRC guidelines are based on the best available evidence.” The spokesman also confirmed that the NHMRC is working with the Department of Health on a review of the guidelines.

But will the revised guidelines make any difference and is there any hope of international consensus on the research?

Robin Room points out that medical research has come a long way since 1987. But Richard Smith believes the science behind the advice remains weak: “We know that the minute you drink any alcohol you increase the risk of certain cancers. With smoking we can say ‘don’t smoke’ because it’s based on firm evidence, but we don’t have the firm evidence yet for alcohol limits. Randomised trials and cohort studies, where you ask people how much they drink then see what happens over a very long time, are weak because people tend to under-report their consumption. In the latest UK guidance, they suggest you should have a few days a week where you shouldn’t drink at all. It’s good advice and I try to live like that but I can’t see that it’s based on any form of science.”

Professor Michael Farrell, director of the National Drug & Alcohol Research Centre at the University of NSW, believes it is not so much the evidence on which guidelines are based that’s the problem but the fact that the guidelines themselves have no resonance with the population as a whole. “In Australia we have a long culture of heavy drinking, and the limits set by the guidelines don’t ring true to what our friends are doing. We know that less is better, but what is less?” Farrell says.

“There’s a problem of exactitude of risk; with smoking and lung cancer, we know that for a lifelong smoker the risk is 25 times that of a non-smoker but we don’t have such clarity of evidence with drinking. Some say one drink is safe, others say there’s no safe level. It’s one thing to do the figures around it, another

to decide who’s taking the risk and how to communicate what risk people are taking.”

Others go further, suggesting that alcohol guidelines themselves may be causing harm. Professor Sally Casswell, a social scientist at Massey University in New Zealand, who has studied international protocols including those of Australia, accuses governments of using guidelines to step back from responsibility, forcing that role on individuals while the

alcohol industry thrives. She also points out that the guidelines encourage people to drink up to the daily limit, rather than keeping below it. “Guidelines are very much aligned with alcohol industry messages; they are so broad as to be meaningless and may actually be dangerous as the subtext normalises alcohol use: Everyone drinks, just do it sensibly,” she says.

So, what is the answer? Some doctors believe more powerful action is needed. In a recent submission to a Senate inquiry on domestic violence, the Royal Australasian College of Physicians asked for the minimum purchasing age for takeaway alcohol to be raised (they did not specify to what age) and for blood alcohol levels to be reduced to zero for all drivers.

Most of those I spoke to are in favour of greater regulation of the industry, including

raising the price of alcohol, arguing that a steady increase in price would reduce the amount we drink, much as it did with smoking. However, they’re pessimistic about the government’s readiness to take on the alcohol industry. In a recent blog post after a debate with members of the alcohol industry and other scientists, Richard Smith wrote: “I left understanding more clearly how politically difficult it can be to do what seems sensible and obvious to doctors.”

But there is some optimism. Most experts believe that as the linkage data becomes clearer, people will be more likely to lower their consumption. “It’s a changing culture. We’ll probably be drinking less in a decade’s time because of health awareness,” says Farrell.

In the meantime, while the protocols may not be ideal, at least they do make us think about how much we’re drinking. As Farrell points out: “The alcohol industry doesn’t like the guidelines so that means they must be doing some good.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout