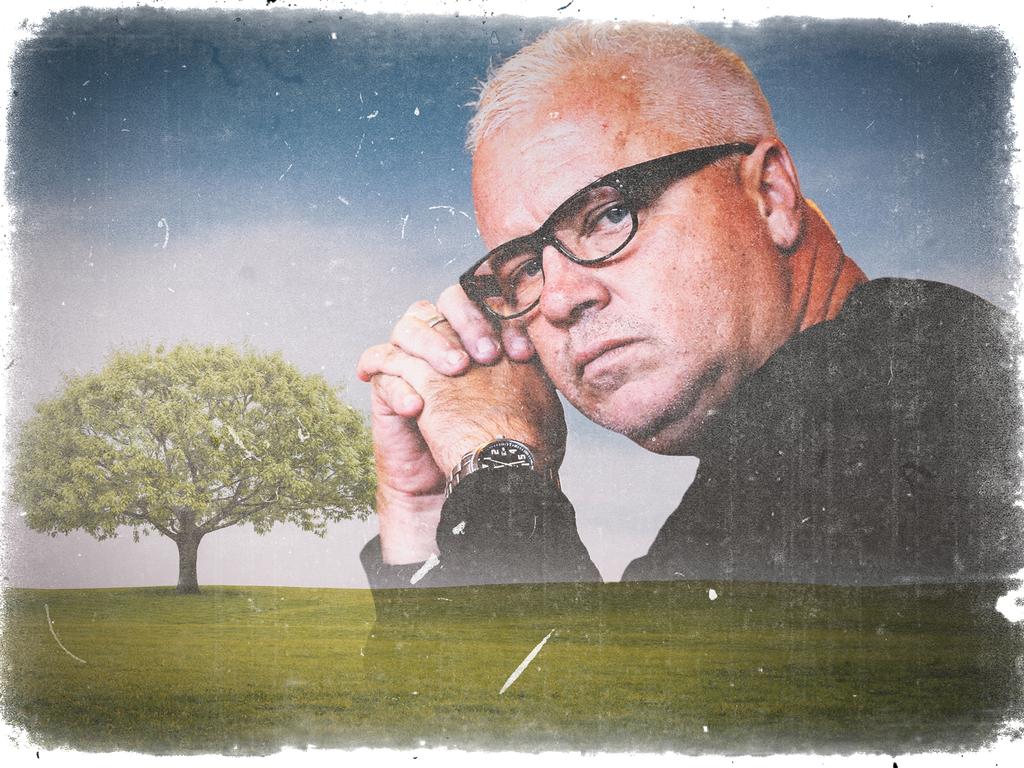

An unexpected drama in the family paddock taught me valuable lessons about grief and loss

A warning to horse lovers. This story may distress but it may also instruct in how to approach life in the way only animals can teach us.

This is a difficult story to tell but they say one of the best ways to deal with grief is to share your experiences, so here goes.

A warning, though, to horse lovers. This anecdote may distress. But it may also instruct in how to approach life in the way only animals can teach us.

We have two rescue horses. Both are in their late 20s or early 30s. They say the best way to convert horse years to human is to multiply by 3.5. So Jessie and Tassie, both males, are close to centenarians.

They’re impressive for old codgers.

Jessie, a thoroughbred, was a racehorse in his heyday. You can tell. When he gallops up the paddock for his evening feed he still rounds a corner like he’s entering the straight at Randwick. And I swear there’s a glint in his eye that I don’t think is age-related conjunctivitis.

Our other horse is Tassie, an Arab, who has all the classic characteristics of his breed – the high tail, the broad forehead, the concave facial profile and the petite muzzle. From day one Tassie has always acted like he’s only roughing it in Australia on a brief holiday from Ascot, Berkshire. He behaves like he has royal lineage and will soon be returning to an airconditioned stable and private chef back in Blighty.

Jessie and Tassie, as it turns out, are best mates, and they have quite a backstory.

During the devastating floods in far northern NSW in 2021, both horses were happily living out their lives with other owners on a large property when Tassie got swept into floodwaters.

According to their then owners who witnessed it, Jessie, the bigger horse, immediately leapt into the torrent and dragged Tassie to safety by his mane.

That would not only suggest, but scream, an inseparable bond between these two old timers.

When the owners sold their place two years ago, and the new owners didn’t want any livestock on the property, my wife took them in and they became family.

Jessie, we learned quickly, was the boss. He’d munch halfway through his evening tub of lucerne and, yes, his Old Timer seniors horse feed, then head over to Tassie’s bucket, chase him off, inspect the volume and either stick with it or return to his original bucket.

Can the grass always be greener for horses? It is for Jessie.

By and large, Jessie is level-headed, relaxed, affectionate. In his paddock, which is effectively his nursing home, Jessie is the elderly gent in the rocker on the veranda, peering over the top of his spectacles now and then, smiling and nodding at passers-by.

Tassie, however, is snappy and dramatic, a nipper who is never satisfied, a strutter, a horse you sense feels he deserves more illustrious company.

Then last week, in the aftermath of weeks of constant rain, the fields spongy underfoot and Tassie’s fence line path – carved by him over months with his relentless prancing back and forth – was a muddy bog.

At dusk on this seemingly uneventful day we brought them down their usual evening meal. Both horses were side-by-side, waiting at the fence as they had done for the past 700 evenings or so in our care. The next minute, literally in the blink of an eye, Tassie slipped in the mud and was down.

The slip was so quick we didn’t see it. Up one second, in a heap the next.

Come on, Tassie, we shouted, thinking he was being his usually histrionic self, up you come. Dinner time.

But he didn’t get up.

He tried several times, attempting with great effort to hoist himself upright with his front legs. But his back quarters wouldn’t co-operate. Tassie, don’t be silly, let’s go.

Still he remained down.

Jessie buried his nose in his feed bucket as always. Tassie, fully attentive, the nostrils alert to the food, the evening dinner ritual at the setting of the sun, the coat adjustments, the brushing, the carrot desserts, simply could not return to all fours.

After an initial vet visit with an uncertain diagnosis – snake bite, just old age, colic, mud scour? – the horse lay there all night beneath a wash of stars and blankets. My wife sat there in the chilly dark by his side, administering pain relief for whatever might be causing him pain, until dawn.

Let’s see how he is in the morning, the vet had said. Perhaps he’s just being a dramatic Arab. He might be in shock. He might get over it.

My wife reported that throughout the overnight vigil Jessie stayed close to his prostrate mate. Licked at a cut Tassie had suffered on a barbed wire fence during his fall. Nuzzled and nudged him. Whinnied. Then neighed.

On several occasions Jessie took off at full gallop towards their small stable across the paddock, turned and raced back. He was encouraging his friend to get up and at ’em. To rise and join him. They were always side-by-side. Inseparable.

The second vet visit first thing in the morning confirmed that old Tassie had broken his back in that slip in the mud, and his rear end was paralysed. Those old bones had finally given way.

Tassie was still alert. He took some water from a sponge. Devoured dollops of molasses on his tongue. Looked achingly for his morning carrot treats. But his body had failed him.

The vet put him down peacefully. Leave him here for a while so that Jessie can get used to what’s happened.

And so Jessie stood by the side of his dead mate on and off throughout the day. He rarely looked down at the body, just straight ahead as if in a daze. Sometimes you’d swear he was guarding his old buddy.

In the afternoon Jessie started neighing. Loudly and repetitively. His whole substantial torso shook with the effort. You could hear his cries across the fields.

Cows on the neighbouring property stopped and stared at him.

Before dusk we silently buried Tassie in a deep grave not far from where he fell.

For the next day, Jessie kept up his mournful cry.

He has settled now, but you’d swear that after that traumatic period he has lost a little of his lustre. That the glint in the eye has diminished. We’d see him just staring across the paddock. He looked lost. Because he was.

Our kids were courageous during the ordeal and learnt some valuable lessons about life and death. About loss. About grief. I knew that in the future, when they needed to draw strength in a comparably difficult human situation, they’d remember Tassie’s struggle for life, his death and Jessie’s extraordinary loyalty.

There was dignity in this unexpected drama we found ourselves in. And the gift of quiet instruction from the animals.

Why, in our mad worlds, do we only cry that life is precious and short when death is on our doorstep?

A couple of days after Tassie passed my daughter showed me a story she’d found on the internet. It was about a 15-year-old horse called Peyo. Peyo lives in Calais, France, and visits and comforts patients in a palliative care hospital. They call him Doctor Peyo.

Peyo’s trainer, the story went, had learned early on that Peyo was somehow attuned to human distress and illness and in his own way offered solace with his presence.

My teenage daughter smiled even with tears in her eyes and quietly nodded at me. I nodded back. We didn’t need to say anything.

They might have Peyo of Calais.

But for a precious while, we had Tassie of Mullumbimby.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout