When investigating your family tree, you might be surprised at the explosive stories you shake loose

What hidden health secrets lie waiting in your family tree – just like a stick of old explosives?

The man I was having morning tea with recently was someone I’ll call Jack.

Jack was in his 70s and was kindly and affable and interesting. I liked him a lot from the moment I met him. There was one other thing – his fine English facial skin was instantly recognisable.

It was the skin of my maternal grandmother. And my own mother. And a whole side of the family that had migrated to Australia from the UK and put down new roots in Brisbane, Queensland in the first quarter of the 20th century.

Jack, it turned out, was a distant cousin I never knew I had. I was conducting some family research and was stunned to learn that Jack, the son of a man who was brother to my great-grandmother (read that slowly – if you’re like me, family trees can warp the brainbox).

So here was Jack, as if conjured out of nowhere, a familial rabbit from a hat. Yet we shared blood. He was fit and well, and wrapped in that delicate, non-sun-ravaged skin that came out of Greater London, a significant pin on the map on one side of my family tree.

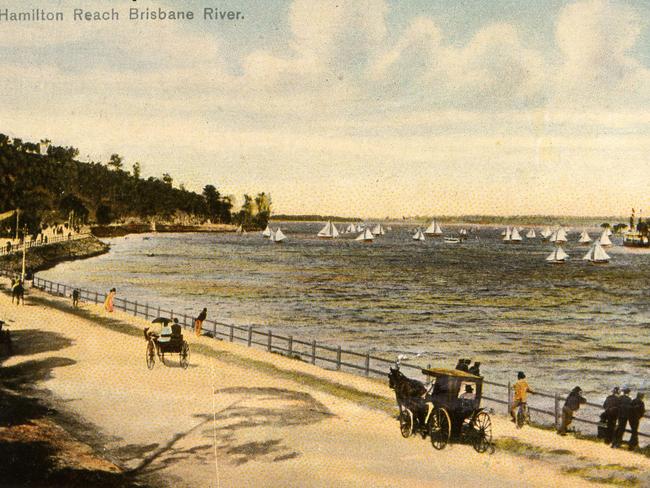

Shockingly, too, he had lived in and around the Brisbane suburbs where the family had originally settled after migrating, leaving a northern hemisphere winter for a blistering Queensland summer. You know what they say about falling apples.

How had I not known of Jack’s existence? I reasoned that this was not peculiar. I had found him, a leaf on the tree, only because I’d been carefully studying that singular branch of the family line.

I wanted information on my great-grandmother, Mabel, who had drowned in Norman Creek in Brisbane’s inner eastern suburbs. So said her official death certificate. Cause of death – drowning. But the story had been whispered through the decades that she had actually taken her own life. I wanted to know about the sort of life she lived that brought her to the edge of that creek in the 1950s.

So I needed to find living members of Mabel’s family. Thus, Jack.

Most people find it difficult to recall the names of their great-grandparents, let alone the various aunts, uncles and cousins, great or otherwise, who sit on their genealogical branch.

In the end we all get swept away in those eternal waves of generational amnesia. Unless we have behaved so repulsively that even the stench of our long-dead actions rises to the surface and demands attention.

But by and large we blunder forward, rarely looking in the rear-vision mirror at these legions of human beings who preceded us.

Our family story is not new, though it remains surprising.

Jack’s family lived in the next suburb to Mabel’s. Yet they never visited. They rarely communicated. They may have been living separately in different parts of the world.

Mabel, it appears, had taken up with a disreputable lot (my side of the family) and been quietly excommunicated from her brother and the life he had established in the adjoining suburb in Brisbane.

So much so that Jack never knew any details about my lot. He was told nothing. He was encouraged to steer clear of great-aunt Mabel and her clan just a few streets away.

Jack’s lovely wife, who enjoyed genealogy, had tracked me down and sent me an email some years ago. I reconnected in my hunt for details about Mabel’s mental health and her death. And that’s how we met for coffee and cake in a cafe in Brisbane, long after much of both sides of our family tree had withered away.

Jack knew no details of Mabel’s death in Norman Creek but, given his physical likeness to some of my relatives, I asked him if he was aware of any history of mental illness on his side of the family fence.

“Anxiety,” he said. “A strong streak of anxiety going way back. And my grandfather was diagnosed with breast cancer in his 90s.”

I was momentarily startled. Not at Jack’s revelation, but at my own ignorance. In dealing less than flippantly with the very genetics, the accumulation of building blocks that had somehow resulted in me, I was ignoring possibly critical information about the composition of my own present and future health.

Anxiety, Jack said.

I knew for a fact that Mabel’s son, my grandfather, had married into a family also riven with anxiety. The flow of it was so potent that it had left my maternal great-grandmother dead in a mental health institution outside Brisbane in the mid-1950s, just a few years before Mabel’s own demise in that suburban creek.

Those psychological issues had flowed through to my maternal grandmother. Who knows how far they reached back into our family line?

I came away from the meeting with Jack wondering why the issue of examining genetic lines for predictors of health and wellbeing, or establishing not just a family tree but a “medical pedigree”, was not, in my experience, more paramount and worthy of serious attention.

Perhaps that wilful ignorance was part of my genetic make-up.

I told a friend about my meeting with Jack and she said that maybe I needed to try to put together a “genogram”.

A what?

It’s obvious that innocuous traits that can be flung down a family line (Jack’s fine British skin, etc) So the opposite must apply. That there is also the possibility that darker matter can insinuate itself in the family tree.

A genogram can go beyond the surface of that tree and map behaviours and traits that may have been handed forward, like a baton, to unsuspecting generations.

According to Understanding Genetics, produced by the Genetic Alliance in the US in 2008: “Family history holds important information about an individual’s past and future life. Family history can be used as a diagnostic tool and help guide decisions about genetic testing for the patient and at-risk family members. If a family is affected by a disease, an accurate family history will be important to establish a pattern of transmission.

“A family history can also identify potential health problems such as heart disease, diabetes, or cancer that an individual may be at increased risk for in the future. Early identification of increased risk may allow the individual and health professional to take steps to reduce risk by implementing lifestyle changes, introducing medical interventions, and/or increasing disease surveillance.”

A study – Epigenetic signatures of intergenerational exposure to violence in three generations of Syrian refugees – published in Scientific Reports in February looked at the “biological impact of trauma” over several generations.

In this instance, researchers studied DNA from 48 Syrian families across three generations, focusing on mothers and grandmothers who had been impacted by Syria’s civil war.

The study looked at changes in the “epigenetic signatures” of these women, or chemical alterations in their DNA sequence due to stressful environmental factors.

According to Science Alert: “The changes observed by the researchers were consistent across victims of violence and their descendants, suggesting that it was the stress of conflict that had changed the chemical messaging associated with these genes.

“These kinds of lasting, multi-generational gene changes in response to stress have previously been observed in animals, but until now there’s been little research into how this might also work in people.”

While my family’s intergenerational blips pale in comparison to the Syrian experience, it did make me appreciate the importance of examining the past as a possible window to the future.

Then I assessed the amount of time and effort required to build a family genogram.

Firstly, a possible genetic trait in me reared itself immediately – lack of patience.

Secondly, I reasoned that if I did dedicate myself to this task, I wasn’t confident I’d have the years in me to complete it. It seemed ironic that you could be outlived by an attempt to create a data repository aimed at extending the lives of your family members, not the least you.

So, like almost everyone, I’ll drive forward. And not pay too much attention to that pesky rear-vision mirror.

Which makes me anxious, a condition I now know decorates my family tree like a sweaty stick of gelignite.

Sitting opposite him as I sipped coffee and munched on a large pretzel, it was clear this wasn’t the sort of thing that happened every day.