The Dismissal: Palace letters settle this debate — Kerr acted alone

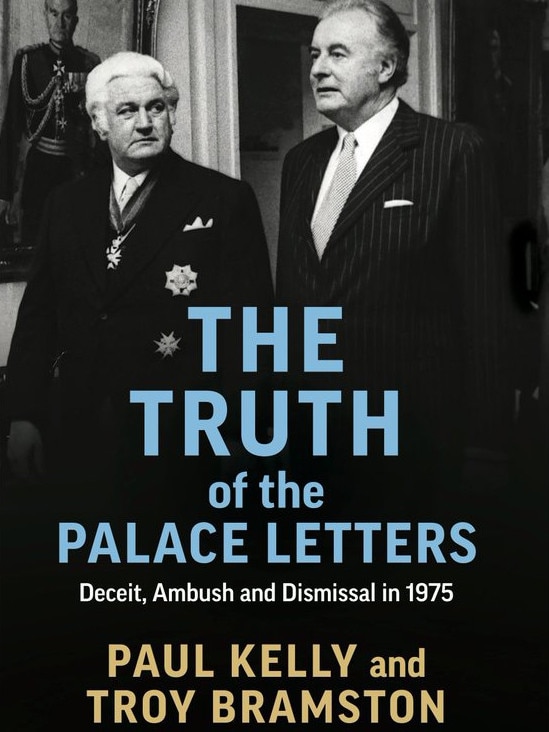

Their conflict is brought into sharp focus in the forewords they have penned for the two competing books on the history — Keating in the book Troy Bramston and I have co-authored, The Truth of the Palace Letters: Deceit, Ambush and Dismissal in 1975, and Turnbull for the Jenny Hocking book, The Palace Letters. The extraordinary backdrop is that Turnbull and Keating co-operated in the 1990s when Keating as prime minister orchestrated a major review leading to his commitment to pursue an Australian republic and his advice to the Queen when they met at Balmoral on September 18, 1993.

In his foreword and interview with the authors Keating recalled that historic meeting: “In the poignancy of this moment the Queen sat with her dignity and the long history of her family and I with the aspirations and live mandate of a people.”

The Queen took Keating’s advice. “We would expect no less of you and ask no more,” Keating told the Queen. And he made an important promise. He told the Queen the Australian people appreciated her long efforts and that “it was not my wish nor the government’s to involve her in any way in the current debate”.

Keating saw the republic as being about Australia’s future, not its past. But a long shadow has now fallen across the Keating invocation. There is a new revisionist view oscillating around a range of propositions — that the Queen authorised the Dismissal, that the palace gave the Dismissal the “green light”, that the palace encouraged the Dismissal or, finally and feebly, that the palace in the form of the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, should have intervened to protect Gough Whitlam.

Turnbull and Keating disagree on the fundamentals — whether the Queen was implicated in the Dismissal. Reviewing the context of the palace letters Keating said: “I think it is a mistake by the republican movement to suggest, in some way, we should move to become a republic because the Queen was trying to use an old power through the catspaw of the governor-general. I don’t believe the Queen ever thought this or was culpable about this or was culpable in 1975.’’

Turnbull disagrees. In his foreword Turnbull asserts: “Kerr made it very clear to Charteris that he was contemplating dismissing Whitlam and Charteris did nothing to discourage him.”

Indeed, he goes further. Turnbull lays the charge against the palace that the Charteris letters “can be read as encouraging” Whitlam’s dismissal.

While this falls short of a full indictment, it makes the Palace and Queen complicit — thereby endorsing the revisionist interpretation, a view never embraced by Whitlam himself. Whitlam was convinced the palace would never have entertained the idea of his dismissal, a point he made to me on many occasions.

The Queen has been on the throne for 68 years with no record of intervening in other nations where she is head of state to terminate or push out prime ministers she doesn’t like. Why would the palace seek the political liquidation of Whitlam in defiance of its monarchical obligations, contrary to the Queen’s character and for no known reason since both Charteris and Queen enjoyed cordial relations with Whitlam?

Turnbull offers no answer. It is entirely unsurprising that the Buckingham Palace letters offer no support for his view, which seems to rest on a misinterpretation and mispresentation of the palace letters, raising the question: why would Turnbull engage in this process?

Governor-general Sir John Kerr’s method through the crisis was to cultivate the palace, endlessly run through his options but constantly tell the palace he had not made up his mind one way or the other. He persisted in this to the end. Take Kerr’s last pre-dismissal letter to the palace, dated November 6. He knows the climax is approaching and we know — from Kerr’s own papers — that he was starting to plan a dismissal.

But Kerr keeps that secret from the palace. At the end of this letter Kerr concludes that “an important decision one way or the other may have to be made by me this month”. A decision “one way or the other”. This is Kerr in the final paragraph of the final letter to the palace before the Dismissal.

He doesn’t come clean. He is keeping the palace guessing, keeping them in the dark, keeping them unsure of how any resolution might be effected. This was Kerr’s method in dealing with the palace — cultivate them but don’t tell them.

Before the Dismissal Kerr never told the palace he had decided to dismiss Whitlam, never told them when or how, never told them he would deny Whitlam the chance to go to the election as prime minister or that he had advice from the chief justice supporting dismissal.

Did Charteris do nothing to discourage Kerr from a dismissal? The answer is obvious: Charteris didn’t know Kerr was embarking on a dismissal or any of its details. All Charteris knew from Kerr’s letters was that resort to the reserve powers was an option — and that included dismissal as an option. And, acting on this knowledge, Charteris penned his decisive letter of November 4 directly warning Kerr against a dismissal.

He begins by telling Kerr the reserve powers exist — a truism. Anyone who doubts this should read the 900-page book The Veiled Sceptre by Anne Twomey, an exhaustive study of the multiple applications of the reserve powers in Westminster systems. As Twomey said: “There is nothing shocking or surprising about the statement by Charteris that the reserve powers exist. It is not possible to say that such powers do not exist when they are still being used in numerous countries.”

Charteris then told Kerr the real “value” of the reserve powers was their non-use; that is, their role as a backup for a governor-general giving a prime minister a warning. Indeed, this is their main use.

Charteris followed up by saying the reserve powers should be used only in the “last resort”, said the threshold had not yet been passed to a “constitutional” crisis and finally said the reserve powers should be used only “at the very end when there is demonstrably no other course”, the point being there is always another course — the warning role of a sovereign and governor-general.

It’s unambiguous and the language is direct. If the English language has any meaning this constitutes a strong discouragement to Kerr over actual use of the dismissal power. What the palace understood by the reserve powers encompassed the warning mechanism as referenced by Walter Bagehot — not just the more lethal dismissal act itself.

And if Kerr had warned Whitlam, there would have been no dismissal of the prime minister. Sure, the warning might have triggered other events, but there’s one certainty: Whitlam wouldn’t have sat pat and gone meekly to a dismissal he saw coming. The proper role of the governor-general was to warn and this was the view of the palace.

If you want to grasp whether the Queen was complicit in 1975 and are stranded between the Keating and Turnbull versions, it’s no contest: put your judgment on Keating for common sense and documentary evidence.

Turnbull used to boast about his rationality as prime minister but that’s missing in action on the 1975 question, pivotal to our history.

The Truth of the Palace Letters: Deceit, Ambush and Dismissal in 1975, by Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston, is published by Melbourne University Press.

Wednesday lunchtime heralds the 45th anniversary of the dismissal of the Whitlam government with a strange fate having befallen this event — the fundamentals of the Dismissal are in dispute, with former prime ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Paul Keating offering conflicting accounts.