The Palace letters: Sir John Kerr’s role in the Whitlam dismissal

The Whitlam dismissal in 1975 was a conspiracy by the Queen’s representative in Australia, not the Queen.

After the most dramatic day in his life, Sir John Kerr retired to his study on November 11, 1975 to write to the Queen, Australia’s head of state, to explain his dismissal of the Whitlam government, an action he took in her name. The emotional and constitutional showdown with Gough Whitlam at 1pm that day remained, he said later, “engraved upon my mind”.

By Kerr’s standards this letter was brief. But writing to the Queen was central to his constitutional duty. Throughout the crisis Kerr informed Buckingham Palace of the events — but Kerr operated on one overarching principle: if vice-regal intervention was required, it would be his decision alone and done in his way.

As a proud man who had become governor-general after having once dreamt of becoming prime minister, Kerr would now leave his own mark on history. “I did not tell the Queen in advance that I intended to exercise these powers on 11 November,” Kerr said later. “I did not ask her approval.” Seeking such approval would have been constitutionally flawed, politically dangerous and beneath Kerr’s pomposity.

Kerr knew the Queen had no legal role to play in the crisis. The powers of the sovereign are exercised in Australia by the governor-general. Indeed, this was the basis on which Kerr took the job. He did not become governor-general to outsource his influence to the Palace. His obsequious cultivation of the Palace had one constant motive — to buttress his own autonomy. The dismissal, in each of its cumulative decision-making steps, was an Australian project.

In his letter written after the dismissal, Kerr now informed the Queen through her private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, of something truly remarkable — an elaborate, secret and extraordinary plan he had implemented, none of whose components he had previously disclosed to the Palace. These were that he had decided on a November 11 dismissal in a Government House ambush; that Whitlam had come to request a half-Senate election that Kerr would deny him since there was no guarantee of supply; that he had consulted chief justice Sir Garfield Barwick the previous day, thereby tying the High Court to the dismissal; that Barwick had advised Kerr his intention was consistent with “your constitutional authority and duty”; that he would deny Whitlam any genuine opportunity to go to an election as prime minister; that his plan had involved commissioning Malcolm Fraser as caretaker and minority prime minister to provide advice to the governor-general; and that, acting on Fraser’s advice after supply had been secured, he had dissolved the parliament for an election.

Before November 11, Kerr had told the Palace none of the above — absolutely nothing. The Queen was hostage to Kerr. None of the incendiary steps that he took that turned November 11 into the biggest constitutional and political controversy in Australia’s history was cleared with the Palace. The Queen was not told he had decided to dismiss Whitlam nor the extraordinary manner of the dismissal — cutting Whitlam down in a constitutional strike at Yarralumla. History tells us this was not the way the Palace behaved.

The governor-general wrote lengthy letters to the Palace, but what he didn’t say was far more important than what he did say. The Palace was informed about his thinking and his options. It was told nothing about his elaborate plans that were being put in place from November 6 onwards. Keeping the Palace in ignorance was a deliberate strategy.

In his letter Kerr said: “I should say that I decided to take the step I took without informing the Palace in advance because under the Constitution the responsibility is mine and I was of the opinion that it was better for Her Majesty not to know in advance, though it is, of course, my duty to tell her immediately.” He provided the briefest account of the exchange with Whitlam at the point of dismissal, saying that, on being informed, Whitlam said: “I shall have to get in touch with the Palace immediately.” Kerr told him that would be useless as he was at that time no longer prime minister.

The key point was Kerr’s determination to have the issue resolved then and there in his study. He was determined not to let Whitlam get away from Yarralumla without an election. Whitlam was on Kerr’s territory. He was alone — without staff, without support. The Queen was asleep when Kerr terminated the prime minister.

According to Whitlam, Kerr passed him the dismissal letter and Whitlam asked: “Have you discussed this with the Palace?” Kerr replied: “I don’t have to and it’s too late for you. I have terminated your commission.” He told Whitlam that “the chief justice agrees with this course of action”. Whitlam shot back: “I advised you that you should not consult him on this matter.” According to Whitlam, Kerr shrugged his shoulders and said: “We shall all have to live with this” and Whitlam replied: “You certainly will.”

It is noteworthy Kerr told Whitlam the chief justice agreed with the dismissal. But he made no comment about the Palace. If the Palace had agreed in advance — as some commentators assert — then surely Kerr would have said so. He would have loved to have upstaged Whitlam by telling him the Palace was on his side. But Kerr said nothing of any “royal green light” from the Palace, for the obvious reason that there was no such prior approval.

The Palace was first informed of the dismissal late at night when David Smith, Kerr’s official secretary, rang during the afternoon of November 11, Australian time. His call was taken by William Heseltine, assistant private secretary to the sovereign, and an Australian. Heseltine said: “I was asleep in my virtuous bed in an apartment in St James’s Palace when the telephone rang. I said, ‘Hello David, what on earth are you ringing for at this time of night?’ And he said, ‘Well, the governor-general has dismissed the prime minister.’ The double-take of all time. I can’t remember what I said to him but the reaction was stunned surprise.”

Whitlam also rang the Palace and spoke to Charteris. In his letter to Kerr written six days later, Charteris described the phone conversation: “Mr Whitlam prefaced his remarks by saying that he was speaking as a ‘private citizen’; he rehearsed what had happened, the withdrawal of his Commission, the passing of Supply and the votes of no confidence in Mr Fraser and of confidence in the Member for Werriwa, which had been passed by the House of Representatives, and said that now Supply had been passed he should be recommissioned as Prime Minister so that he could choose his own time to call an election.” The Charteris letter offers only one interpretation: Whitlam wanted Charteris to speak to Kerr on his recommissioning as prime minister. Whitlam omitted this point from his own account when he said: “After the drama of the day I telephoned a good friend in London, Sir Martin Charteris, soldier, diplomat, sculptor and Private Secretary to The Queen. It is a fact that The Queen’s representative in Australia had kept The Queen in the same total ignorance of his actions as he had the Prime Minister of Australia.” Whitlam did not believe the Palace had any role in his dismissal.

The Queen was informed of the dismissal at a meeting with Charteris and Heseltine at the Palace in the early morning. Heseltine said: “I can’t remember whether she was in her dressing gown. I think she had got dressed already for breakfast … I think she was indeed surprised, as surprised as we had been. She certainly gave no indication to me that there had been any thought that something like this would happen.” Asked about the Queen’s view of the dismissal, Heseltine said: “Ha, ha, I think she is an old and wily bird about her own views … I’m reasonably confident myself that she thought it could have been handled better.”

Drawing upon her experience in studying the Palace, Sydney University professor of constitutional law Anne Twomey said: “For all her reign, the Queen has protected her self-interest in not becoming involved in political or constitutional controversies. Whenever a constitutional crisis has arisen including a ‘race to the Palace’, the Queen has employed the tactic of ‘masterly inactivity’ in the hope that the crisis would be resolved domestically so that she would not have to become involved. Normally that tactic is successful.”

A careful reading of the Palace letters shows they rested on two shared assumptions — that the Queen had no constitutional role in the crisis and sought no role, and that the responsibility for any involvement or intervention by the Crown rested entirely with the governor-general. These are the understood rules of Australia’s constitutional monarchy.

As the crisis approached, Charteris was encouraging and supportive of Kerr. On September 24 he wrote: “As I have had occasion to remind you on previous occasions, the Governor-General of Australia does not seem to lie on a bed of roses and it is clear that you may be faced with some difficult constitutional decisions during the next month or so.” On October 2, with Kerr preoccupied with a potential crisis, Charteris wrote: “In all these difficult matters I am sure you are right to keep your options open and not to decide now what you will do in any given circumstances. When an actual crisis comes the circumstances are so often subtly yet decisively different from what was envisaged.”

Once supply had been blocked, Charteris reinforced these sentiments. The Crown wanted the issue resolved without a constitutional confrontation and expressed its confidence in Kerr. Obviously, it could say nothing less. Charteris wrote: “We must of course still hope that the crisis will somehow become de-fused and I am sure you are doing all that you can, properly, to see that this happens. I fear, however, that you are dealing with two resolute and obstinate men.”

As the potential crisis neared, with a growing prospect of some form of intervention by the governor-general, Charteris was emphatic: “I think it is good that people should know that The Queen is being informed but, of course, this does not mean that she has any wish to intervene, even if she had the constitutional power to do so. The crisis, as you say, has to be worked out in Australia.” It was the last letter from Charteris before the dismissal.

This was the essential position of the Queen and the Palace, repeated endlessly — the issue must be resolved in Australia. This reveals not the strength of the Palace but its weakness. Charteris was not master of events in Australia. The Queen, restricted by the Constitution, by geography and by outlook, was little short of a passive but interested observer. It is hardly an exaggeration to say the Queen was hostage to Kerr since he would act in the Queen’s name.

By having the confidence of the Palace, Kerr maximised his own discretion, confident that the Palace would support what he decided. This is apparent from the start. The month before the budget was blocked, Kerr wrote: “If the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition get into a battle in which the Senate has defeated the budget, the Prime Minister refuses to recommend a dissolution, my role will need some careful thought.”

A few days later, still three weeks before the blocking of the budget, Kerr in a long letter told Charteris: “You will note that in what I have written I have expressed no view of what I may do in various contingencies. I think it better to keep my mind and my options open so that if the worst happens I can decide at the last moment what to do. I am however thinking hard.”

On October 20, Kerr told Charteris the Liberal leaders expected him to intervene. But he said: “I do not propose, at this stage, to try to mediate.” On October 27, he wrote that if supply was still rejected and the money was about to run out “the question will ultimately arise as to what I should do”. He quoted from Sir Paul Hasluck’s 1972 lecture on the role of the governor-general that in a crisis the governor-general “can check the elected representatives”.

As November 11 approached, Kerr’s correspondence with the Palace dried up. There was only one more letter to Charteris — on November 6 — before the dismissal. The tone of this letter was different. Kerr’s mind was sharper and his conclusions were tougher. In the penultimate paragraph he told Charteris: “The crisis is now a very serious one and if both parties and their leaders remain adamant, an important decision one way or the other may have to be made by me this month.”

After the dismissal, on November 12, the speaker of the House of Representatives, Gordon Scholes, wrote to the Queen: “I would ask that you act in order to restore Mr Whitlam to office as Prime Minister in accordance with the expressed resolution of the House of Representatives.” This letter was excusable but extremely unwise. It left Labor in the position of asking the Queen to intervene in Australia, secure the dismissal of Fraser and the reinstatement of Whitlam. The Queen had no constitutional power to do this. She would never have contemplated such action. It would have been contrary to the principles on which she operated and would have threatened Australia’s constitutional monarchy.

At his dramatic media conference on the afternoon of November 11 Whitlam revealed his deepest instinct: “Let’s be frank about it — the Queen would never have done it … There’s no act which says it can’t happen, but it hasn’t happened for 200 years in the Westminster system.”

After the letters’ July 2020 release, a Palace spokesman said: “While the royal household believes in the longstanding convention that all conversations between prime ministers, governors-generals and the Queen are private, the release of the letters by the National Archives of Australia confirms that neither Her Majesty nor the royal household had any part to play in Kerr’s decision to dismiss Whitlam.”

Paul Keating was with Whitlam the last time he saw Kerr before the dismissal. Asked about the 1975 crisis and the Palace letters, Keating said the Queen had “never contrived, on this occasion or others, over the long course of her reign, to undermine governments”.

Keating rejects the conspiracy that the Queen was involved in the Whitlam dismissal. He said: “Kerr usurped the kingly powers reserved to a monarch, unused for centuries, and made the Palace hostage to his plan.”

It is to his credit that Kerr consistently argued the Palace letters should be released. He was unhappy with the Palace seeking to keep the letters from public view. Releasing the correspondence allows a conclusive judgment to be made on competing historical versions about the role of the Queen.

The letters confirm there was a conspiracy to remove Whitlam — but the revisionists have got it wrong. The conspiracy was located at Government House, not Buckingham Palace.

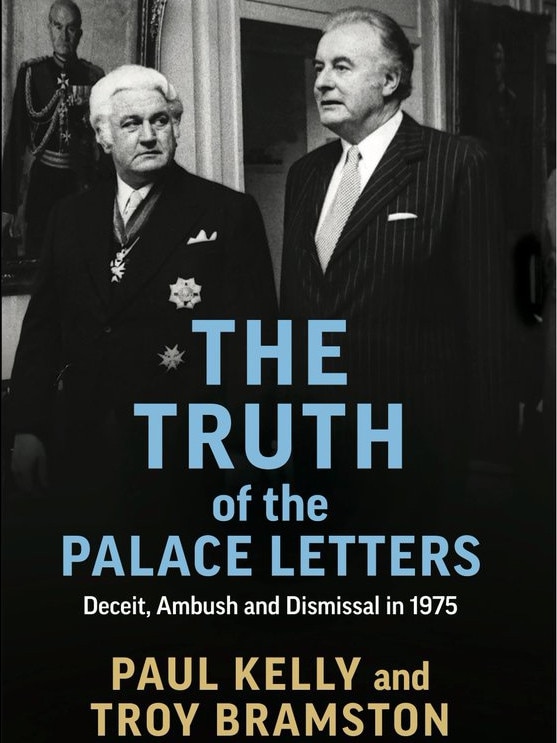

The Truth of the Palace Letters: Deceit, Ambush and Dismissal in 1975, by Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston, is published by Melbourne University Press on November 3.

Register for Discussing The Truth Of The Palace Letters, a special subscriber event.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout