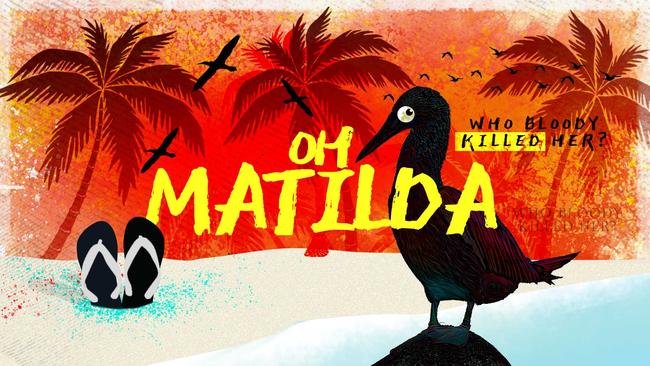

Oh Matilda: Who Bloody Killed Her? Chapter 1

An actress. An island. A gonzo murder mystery. The Australian’s progressive summer novel Oh Matilda: Who Bloody Killed Her? starts here.

This is ‘summer reading’ like nothing you’ve read before: a diverse field of writers, collaborating on a novel that will captivate you through summer.

Each author had just three days to write their chapter, with complete freedom over story and style; it’s fast, fun and very funny.

Tune in over the summer to see how the story unfolds.

Let’s start at the beginning.

-

John McCredden was to be honest a bit tired of people saying they were over lockdown.

He wasn’t over it.

Because it was an interesting time, you had to admit.

He could still walk out the front door, order a coffee from his favourite café; he could still take a stroll around the neighbourhood. He had to wear a mask, of course, but in so doing he had regained some anonymity, which hadn’t been all bad.

There were plenty of books he hadn’t yet read, plenty of podcasts to which he could listen.

Feeding himself of an evening hadn’t proven a problem, since McCredden had many years earlier developed the habit of stepping off the porch, into Aunt Matilda’s Brasserie across the road; now he simply stepped onto the porch and waved cheerily.

A young waiter would soon enough run his order over.

Spaghetti marinara and a half-bottle of red?

Twitter, and a bit of a binge of Tiger King?

McCredden would have been perfectly content to see out the pandemic in such a manner, but then his agent had called, and that’s all anyone needs to say, isn’t it?

His agent had called.

In time, he would remember the old joke: there’s an actor shipwrecked on a desert island, and the rescue boat turns up, and the captain says, look, we’re sorry to tell you, but in your absence, it’s been all bad news, your house burnt down, your wife has run off with your best friend, the pets are dead, your investments are up in smoke.

The actor is shocked.

“Christ,” he says, “Anything else?”

The captain says: “Yes. Your agent called.”

And then of course it’s all okay, because there’s such possibility in those words, isn’t there?

Your agent called.

In just that, there is at least the suggestion of a job.

Never mind that McCredden had by the time of the pandemic already turned seventy; nor that he was already rich — well, all right, but he was at least comfortable — he still wanted work, and why not? He was still hungry; still handsome, more importantly, he was still in demand. Add to that, he was a man proud of his body of work; a man who had paid his dues as a young boy treading the boards at a private school in Western Australia, a man who had set forth for the eastern states, where he’d spent some time as a young heart-throb — it hadn’t sat all that comfortably with him — before maturing into a well-regarded character actor in Hollywood films, one of which had earned him an Oscar nomination.

He could easily have retired, lauded.

But actors don’t retire, do they?

They persist.

They endure.

And so McCredden had listened while his agent explained the concept, and part of him had wanted to say, look, it’s not the worst idea I’ve ever heard.

Except that maybe it was.

Because truly, the idea stank.

But the project was being made for TV and that was all anyone wanted to do anymore, wasn’t it?

Make a series, for TV.

And didn’t McCredden, like everyone, want to be relevant? Didn’t he want to work where the money was, never mind the talented directors? And then his agent had dropped a name that had sealed the deal, the name of a woman McCredden had long regarded as perhaps the best of her generation’s Shakespearean actors, a woman both regal and beautiful, lissom and lovely; a woman with a silver mane, and a swanlike neck, who had only recently gone viral, emerging from the sea in a polka-dot bikini, at the age of 70.

This wasn’t a meeting-your-heroes thing.

McCredden had worked with her twice before.

The first time, thirty years earlier, she had turned up on set with not one, but two companions — an older man for intellectual stimulation, and a younger one for sex. The news had leaked; the tabloids had gone agog; she’d been absolutely unapologetic.

Why, she had airily wanted to know, was everyone suddenly so puritanical?

The second time, they had been in Alabama, and she had arrived alone, to play some kind of indomitable, western plains pioneer. He had found her sitting one night on the step outside her caravan, costume skirts tucked between her knees, and a glass of gin in her hand. They’d gotten drunk, and he’d tried it on, venturing a hand up her thigh.

She had laughed and slapped him away.

They had in the decades since then become email, and then emoji friends, exchanging savage character assassinations from wherever they happened to be in the world, usually under the headline People We Hate.

Now she was in?

Then he was in.

McCredden’s agent explained the terms: filming would take place on a white-sand island off the Australian coast. Two weeks of quarantine. Four weeks of filming. She would take twenty-five per cent of the decent fee; half the rest would go in taxes, but McCredden nonetheless agreed, and Docu-Signed, and soon enough found himself boarding a sea plane. The flight wasn’t long — just 40 minutes — and he’d been seated beside a young actress who took a selfie with him with the singing potato, and then the talking dinosaur filter on his head, causing him to roar with laughter.

Upon disembarkation, they were dropped at their digs, with McCredden deposited outside a wide-fronted, plantation style house, with frangipani trees in pots on the porch.

Dinner was brought to him on a tray.

He spent the evening tapping out tweets and emails, including one to his grandson – the boy lived in Tasmania, with his two Mums — telling him how the island had not just a pizza oven but a teppanyaki preparation zone.

The kid replied with the celebration emoji, and the two balloons.

Just after 10pm, McCredden untied the mosquito nets from the bed posts, and went off to sleep, only to wake around midnight to the unmistakeable sound of a party taking place across the way.

An illegal quarantine party.

McCredden already had one foot on the floor, ready to head over to read the riot act, when he heard a shout, and things soon enough went quiet, and he figured that somebody else had taken care of it.

He drifted back to sleep.

At dawn, he rose from bed, pulled on the cargo shorts and a faded polo shirt over his hairy belly, and went to stand on his wide veranda. A wagtail was bouncing under the purple jacaranda. The sky was a perfect blue.

McCredden was just thinking how this was paradise, when something else caught his eye.

Was it …?

Yes.

His group had on arrival been greeted by island staff with cool drinks in tacky brown cups, shaped like coconuts. One of those cups was now rolling across McCredden’s pristine lawn. Annoyed by the blemish, he went down the front steps, intending to fetch it, and that was when he saw her, curled up on her side in the grass, with one silver sandal resting in the koi pond.

Was she asleep? McCredden stepped closer, then stopped again. She wasn’t asleep. That was obvious. She was dead.

Caroline Overington is a two-time winner of the Walkley Award for Investigative Journalism; she has also won the Davitt Prize for crime writing and the Blake Dawson prize for business journalism. She is a Dylan tragic, a Swans ambassador; the mother of twins, and the owner of Bondi’s oldest blue dog.

Facebook: @carolineoverington

Twitter: @overingtonc

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout