Labor at ‘tipping point’ as Right bids to drive agenda

It should not be a surprise that Labor’s Right faction is reasserting itself on policy and strategy.

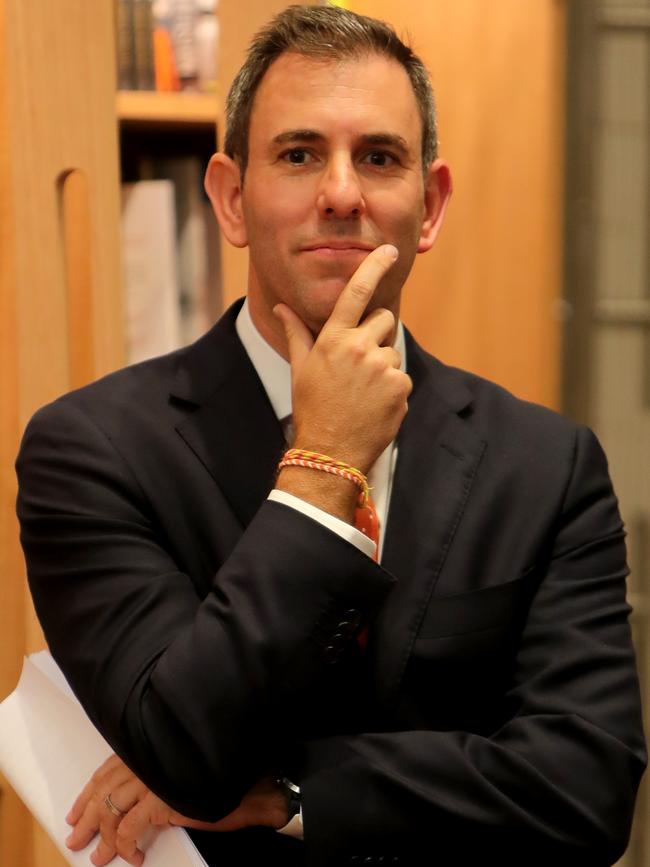

A new book of essays by prominent faction members edited by Misha Zelinsky and Nick Dyrenfurth, The Write Stuff (Connor Court), can be interpreted only as a vote of no confidence in the Opposition Leader. If they thought Labor was well-led and poised for victory, there would be no need for the book.

It makes a convincing case for Labor renewal. The editors set the tone with a searing chapter that spotlights Labor’s fundamental defects. Labor has forgotten how to win elections; it has won a majority of seats at only one election (2007) since 1993. The party is attracting the votes of only one in three Australians. It is not within cooee of returning to government. The editors argue that Labor is at a “historic tipping point” where its survival is at risk.

The party must change to fulfil its mission: seizing power. Tempering idealism with pragmatism is the creed of the Right faction — also known as Unity. They want the Right, which has weakened in recent years, to again be at the forefront of ideas and strategies that can build bridges between constituencies.

“Labor finds itself caught between its more conservative working and middle-class base in Australia’s suburbs and regions and its inner-city progressive activists, and we appear unable to bridge that growing chasm, and unable to build winning national coalitions,” they write.

This is hardly an endorsement of Albanese. Indeed, Zelinsky and Dyrenfurth document that their faction has produced or promoted all of the party’s prime ministers who have won elections in the postwar period. Albanese, of course, has been a Left faction man his entire adult life. Get the message?

Zelinsky, assistant national secretary of the Australian Workers Union, contributes one of the shrewder chapters. He identifies the “cultural divide” that has seen working-class voters, often on high salaries, lost to centre-right parties. He says blue-collar workers feel that “inner-city types” mock their preference for a Bali holiday over Europe, the footy over the theatre, church over yoga and a pub over a wine bar.

A foreword by Stephen Loosley, a former NSW Labor secretary and senator, argues that “fresh ideas and original solutions” to policy challenges are needed “perhaps more than at any time in our recent history”. He reminds us that Gough Whitlam had to reform the party before he could reform the country. And he emphasises that centrist policies are essential to winning votes in suburbs and regions.

Another veteran of Labor politics, Michael Easson, a former NSW Labor Council secretary, urges the party to make room in a broad constituency for voters who are economic and social conservatives, and to be more respectful of people of faith. Sam Crosby, Labor’s candidate for Reid last year, also writes about the importance of faith and reveals his “profound sense of unease” at the attacks on Scott Morrison’s religious beliefs by Labor supporters.

Several of the party’s brightest MPs have contributed chapters: Chris Bowen, Jim Chalmers, Anthony Chisholm, Ed Husic, Richard Marles, Clare O’Neil, Amanda Rishworth and Michelle Rowland. Bill Shorten and Wayne Swan add heft to the book. Even Kristina Keneally — known as a RINO in the faction (Right In Name Only) — contributes a chapter.

The Right’s two main leadership hopefuls, Bowen and Chalmers, offer perceptive contributions. Bowen, recognising mistakes at the election last year, argues that the party must focus on a few key policies and articulate them better rather than “boil the ocean” with a large and complex agenda.

Similarly, Chalmers argues for “ambitious” new policies focused on “the future” and warns that COVID-19 does not mean a return to “big-state socialism”.

Labor has been adrift since the election last year. There has been no fundamental recognition of the party’s poor electoral performance, organisational weaknesses, policy failures or strategic blunders, let alone how to address them. The campaign review last year by Jay Weatherill and Craig Emerson failed to wrestle with these larger challenges, unlike previous party reviews.

Zelinsky and Dyrenfurth note that Labor cancelled its national conference this year. There is no reason it could not have been held COVID-safe online. The result is “there is a vacuum at the heart of the ALP” because there has been no “genuine battle of ideas or vigorous policy debate”.

This is Albanese’s responsibility. Leaders have to lead; that is the job description. When Albanese struggled last week to identify how he would handle the Australia-China relationship differently to the government, and lashed journalists for having the temerity to ask such a question, he said the government needed a strategy. Asked what Labor’s strategy would be, he replied: “Our strategy is to get into government.”

There was, yet again, a collective groan among Labor MPs. The truth is there is no strategy for winning the next election. If there is, Albanese is keeping it secret. It is why the largest group in the Labor caucus is leading the development of policy, organisational renewal and political strategy. Many also are looking for a leader.

As the year draws to a close, the mood within Labor is exceedingly despondent. It is not that most MPs, opposition spokespeople, union leaders, party officials and staff members realise that Anthony Albanese’s leadership is uninspiring and unimaginative. That has long been understood. The next level of despair is recognising that it won’t get any better.