Truth about what makes an award-winning portrait as art prizes celebrate local talent

Two of Australia’s most important portrait prizes are now open, and the winners perfectly illustrate how portraiture should be done.

Portraiture has a long history. The earliest naturalistic portraits were made by the Egyptians, even if in most cases the official effigies of the Pharaohs and aristocracy remained highly idealised and artificially youthful. It flourished in Hellenistic Greece and was eagerly adopted by the Romans: senatorial busts from the republican period anticipate Oliver Cromwell’s famous demand for a “warts and all” account of the subject. Highly sophisticated portraiture continued throughout the imperial period, and then collapsed with the fall of Rome.

For almost a millennium there were no true portraits, or nothing remotely comparable to those we still possess of Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius or even Caracalla. Then the artists of the renaissance rediscovered the portrait, inaugurating the rich history of the genre over the past six centuries. Portraits became ubiquitous in Europe and elsewhere (Gentile Bellini was invited to Constantinople to paint Sultan Mehmet II in 1480), but it became the favourite genre of all in Britain, and to this day holds a special place in all the nations of British foundation including Australia – all of which, unlike many other places, have national portrait galleries.

The Archibald Prize in Sydney, established more than a century ago, is the most famous art prize in the country, even though it – as well as the Wynne and Sulman prizes shown at the same time – has become debauched by a mixture of populism, sensationalism and identity politics in the course of the past few decades. The “Salon des refuses” exhibition that follows each year at the S.H. Ervin Gallery often has a better selection because it picks up a lot of the good paintings that had to be pushed aside to make way for pictures by a checklist of minority groups.

In all of this, the Art Gallery of NSW has lost sight of the founding principle of the Archibald: that a good portrait should be a picture, painted by an outstanding artist, of a significant and distinguished man or woman, preferably one who had made an important contribution to the social, political or cultural life of their nation.

This happened for a number of reasons: there are of course people who think it elitist to prefer good paintings of interesting people; why exclude incompetent pictures of nobodies? And then of course those nobodies could be imagined to be important if they represented a faceless minority, a current political cause, or a fashionable neurosis.

But ultimately, in the case of the Archibald, the exhibition degenerated into a circus in which punters expected shock and surprise, not quality.

Any deeper consideration of what the art of portraiture entails has been long forgotten, which is why so many of the pictures we see alternate between amorphous daubs and superficial likenesses copied from or even painted over photographs. Only in a minority of cases do we discover portraits that represent a true encounter with the subject, whether rendered in a classic, modernist or expressionist style.

As every real painter knows, photographs can be useful resources, but they cannot be the sole reference for a portrait, simply because they register single and static moments of a living and moving process. When artists spend hours drawing or painting the sitter, they discover things that the photograph cannot tell them: they see the features in motion, they perceive how those movements express an inner psychological reality, and indeed they understand that characteristic and repeated movements have actually shaped the face over time.

A photograph, if intelligently taken – like Robert Mapplethorpe’s portrait of Norman Mailer that I mentioned here a couple of weeks ago – can imply some of these things. But even this will not be an adequate source for a painter, because while the photograph is understood to represent a moment in time, a painted portrait is a slowly crafted synthesis of temporal unfolding. This is one of the reasons that photographic portraits are always melancholy: they represent an instant that is gone, vanished into the abyss of mortality in the split second it is taken. In the painted portrait, temporality is acknowledged, duration is assimilated and transience is stabilised.

But the portrait is not simply the record of a personality expressing itself through the facial features, as we might casually assume. If taken too literally, this would imply a misleading dualism, as though the genuine inner self were hidden behind an outer physical shell that was not the true person. In reality, the individual is a composite of mind and body, and the face, as animated and shaped by our thoughts and actions over time, is indeed our identity as an individual. As in the Indian Samkhya philosophy, the self is corporeal or a mental-corporeal composite. What lies behind that, however, and which is not corporeal in the same way, is consciousness; and that is the intangible spark of truly inner life which only the greatest portraits succeed in conveying.

Two of Australia’s most important portrait prizes are currently open on opposite shores of our continent, and as it happens I have to declare an interest in each of them. As one of three judges in this year’s Lester Prize at the WA Museum in Perth, I knew that this would be the case; but then my wife Michelle Hiscock won the Portia Geach Memorial Award at the S.H. Ervin Gallery as well. The exhibitions opened on successive nights in mid-September and run until November.

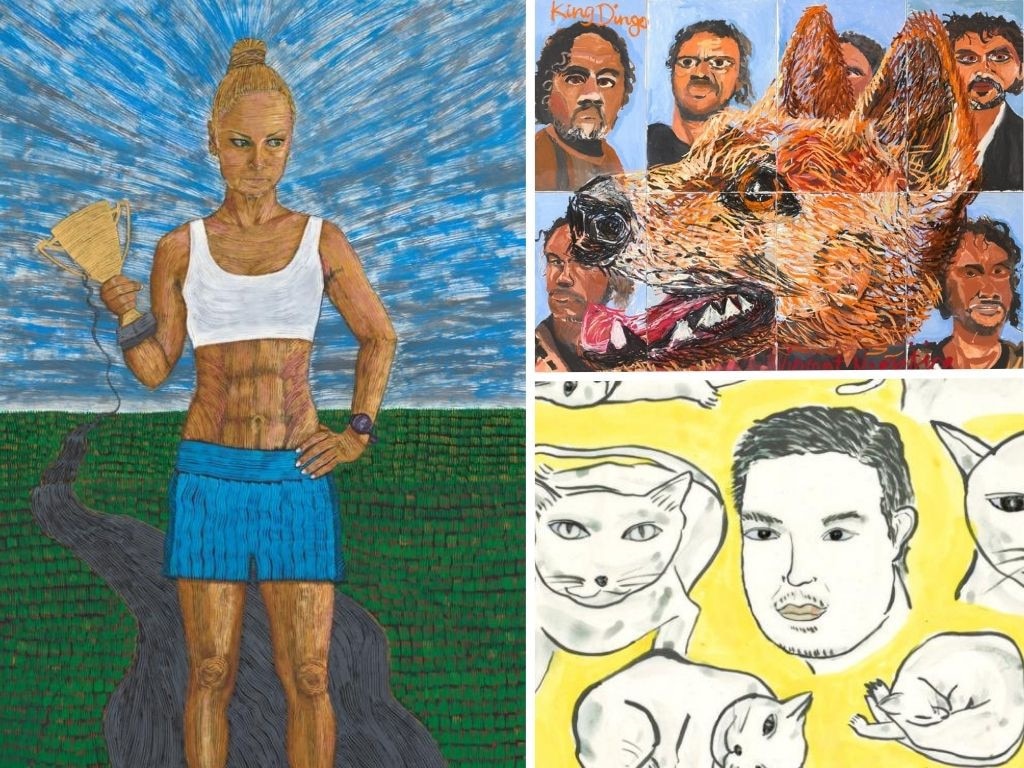

There are a number of good portraits in the Lester Prize, all of which are distinguished by a genuine painterly engagement with the sitter rather than over-reliance on photographs, and an avoidance of gimmicks. The winning painting is a strikingly direct and almost raw self-portrait by Jenny Rodgerson in which, as we said in the judges’ statement, she “confronts her own image in the mirror without posing or flattering herself”. Her nakedness emphasises the search for truthfulness and adds a note of vulnerability. The highly commended award went to Sophie Hann for a portrait of Tsering Hannaford, perched on a stool in a relaxed but lively attitude; the figure is appropriately rendered freely and without unnecessary detail, so that the focus remains on the face, which conveys the intimacy of a mutual understanding between artist and sitter.

Among other commendable paintings, Isabelle Chouinard paints herself in a mirror in her studio, the foreground occupied by the kind of still-life objects for which she is known; the picture is a good portrait, but also an interesting painting from the compositional and conceptual points of view. Another that deserves to be mentioned is Mark Dober’s self-portrait, also painted from life, with a poignant sense of immediacy. At the opposite extreme were a couple of pictures that were at once sensationalist and superficial in their obvious reliance on photography and their attempts to claim credit for moral or identitarian posturing.

The winner of the emerging artist category was Sue Eva, with what looked at first sight like a finely painted still-life of a silver teapot, but also acts as a series of convex surfaces mirroring the artist’s self-portrait in several guises and orientations. The separate Mindaroo Spirit prize, funded by the Mindaroo Foundation, with distinct criteria relating to family and community, went to Sylvia Wilson for a portrait that evoked the power of an Aboriginal matriarch in holding her community together, especially in the breakdown of traditional patriarchal structures.

The Portia Geach finalists also exhibit the usual range of quality. Again there are several commendable paintings, all of course conveying a sense of the substantial connection with their sitters which can only be achieved by spending time with them; usually these are small, and they include two more self-portraits by Isabelle Chouinard and Jenny Rodgerson, a painting of Peter Wegner by Petra Reece and Natasha Ber’s Janet Dawson, among others. On the other hand there are some that rely on tiresome gimmicks and others that are simply not very good.

As usual, some of the worst pictures are excessively reliant on photographs. Among the many things wrong with this process is the inability of the artists to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant or distracting detail. In a couple of cases, the features of the sitter are rendered with less clarity than items of furniture that are uncomfortably adjacent to them. The features themselves – eye, mouth, nose – are frequently misshapen because they are copied from a single flat picture of what is in reality a solid and three-dimensional human head.

Such a limited set of data cannot give a proper sense of what the human face really looks like, let alone understand it as a living and moving system. At best, a photo may be lucky to capture a telling moment or a characteristic expression but again, as already noted, photographs are good at momentary states, while painting condenses time into an image of the subject’s enduring nature. In some of the worst cases, a snap animated by a fleeting grimace has been passively copied or transferred to the canvas, indiscriminately reproducing all the visual data captured by the camera, regardless of whether it serves any purpose in the economy of the painting.

The art is in knowing what to select; what to include and what to leave out. Imagine a novelist opening his tale in a railway station, for example. Is he going to take a photo of the concourse at Central and then painstakingly describe everything he can see in that photo? On the contrary, he is going to select just two or three telling details – perhaps the sense of space, the smell, the announcements of imminent departures – to set the scene and prepare us for the events that are to follow. In the same way, portrait painters should remember that visiting someone and taking a photo of them is not the same thing as a sitting; and that reproducing all the doors, furniture and bookcases that happened to be in that shot is only going to make things much worse.

It is obviously not appropriate for me to say too much about Michelle Hiscock’s winning portrait of Simon Buttonshaw, except that it is successful in part because it avoids such pitfalls. It is based on hours of real sittings with a subject whom the artist has known for many years. It exhibits aesthetic discrimination in focusing closely on what matters and omitting anything irrelevant or distracting.

It is carefully composed within the picture plane, and that composition refers to the historical model of Zurbaran. This model, in turn, is telling and expressive both in echoing the hoods of contemporary surfing culture – with which Buttonshaw was closely associated – and more profoundly in evoking the ineffable solemnity, for one as gravely ill as he is, of contemplating mortality. This is a portrait that speaks movingly, beyond mere likeness or even character, of a deeper and impersonal state of inwardness, awareness and presence.

Portia Geach Memorial Award: S.H. Ervin Gallery to November 2

Lester Prize for Portraiture: Museum of Western Australia to November 16

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout