The truth about the Archibald Prize? It’s full of bad portraits ... with a few exceptions

The media have for years been addicted to the cliche that the Archibald Prize is ‘controversial’, but would never dare question the inclusion of any of the truly incompetent pictures – they are generally made by minorities who are today exempt from criticism.

It’s odd how popular portrait prizes are in Australia. The Romans loved portraits, especially uncompromisingly naturalistic ones, and the Renaissance was fascinated to recover the art of portraiture almost a millennium after the fall of the Roman empire.

The British and the English-speaking peoples have long had a particular fondness for the genre, and are responsible for most of the national portrait galleries around the world.

And yet there is little commercial demand for portraits, apart from the regular and official memorials of monarchs, statesmen, jurists, professors and headmasters, and a smaller number of private commissions. But hardly anyone buys or collects portraits on the secondary market, unless they are by the greatest artists, or of outstandingly interesting individuals.

The truth is that most portraits are fairly ordinary and of little appeal beyond the affection they evoke in family, friends and colleagues. Those that rise above the average do so through the qualities of insight that the artist brings to the encounter with the sitter, the understanding of the subject that develops through hours of observation and conversation, of watching features animated by feeling and understanding the outer appearance as shaped by inner life.

The Archibald Prize usually includes a few pictures that fall into this class but, as I have observed before, these are mainly included as a foil for the lurid, the ugly and the incompetent ones the Trustees include not because they are entirely unaware of their poor quality, but because the exhibition is not intended as a display of the finest portraits of the year; it is designed as a populist entertainment that will shock and surprise and even disgust the punters.

The media, meanwhile, have for years been addicted to the cliche that the Archibald Prize is “controversial”, but would never dare question the inclusion of any of the truly incompetent pictures in the exhibition, since they are generally made by minorities who are today exempt from criticism.

And neither the punters nor the press hacks pause to consider whether a given portrait embodies any intimate insight into its subject, let alone any deeper understanding of the human condition.

It is of course no surprise that there are plenty of bad pictures in the exhibition; and there are so many ways they can be bad.

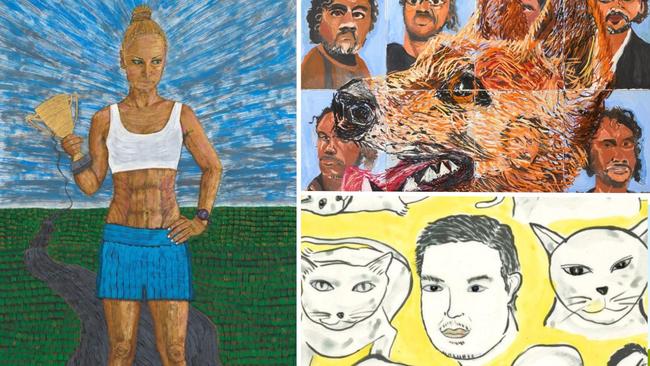

There are crude works and naive or faux-naif pictures by Aboriginal painters. Bodies float in space, full-length figures have their feet inexplicably cut off, and disembodied heads are wrapped in sheets or blankets.

We find the usual tacky hyperphotographic works, in some cases probably printed from photos and touched up; even more pictures are visibly copied from a snapshot with the predictable results, even if camouflaged in bright decorator colours, rendered in po-faced monochrome, or disguised by some kind of fake painterly surface texture.

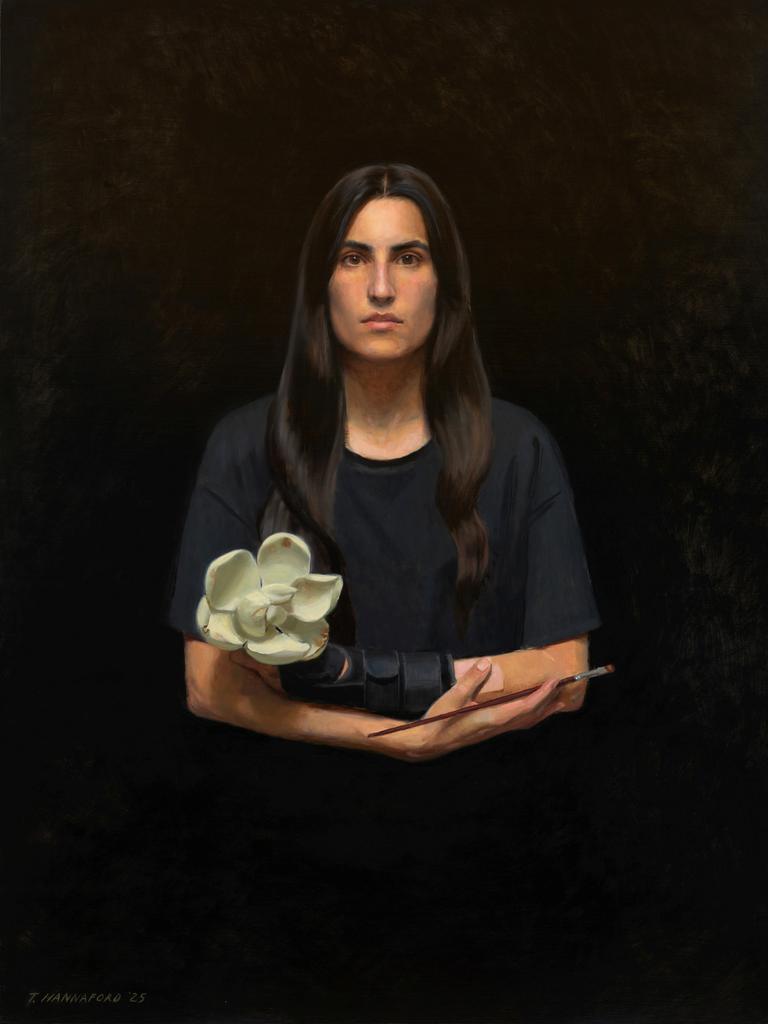

Among the pictures that deserve closer attention is a fine self-portrait by Tsering Hannaford, all the more impressive because it was executed with her left hand while her right was out of action; she is dressed in black, set against a black background, and stares directly at the viewer, probably alluding to Duerer’s great self-portrait of 1500.

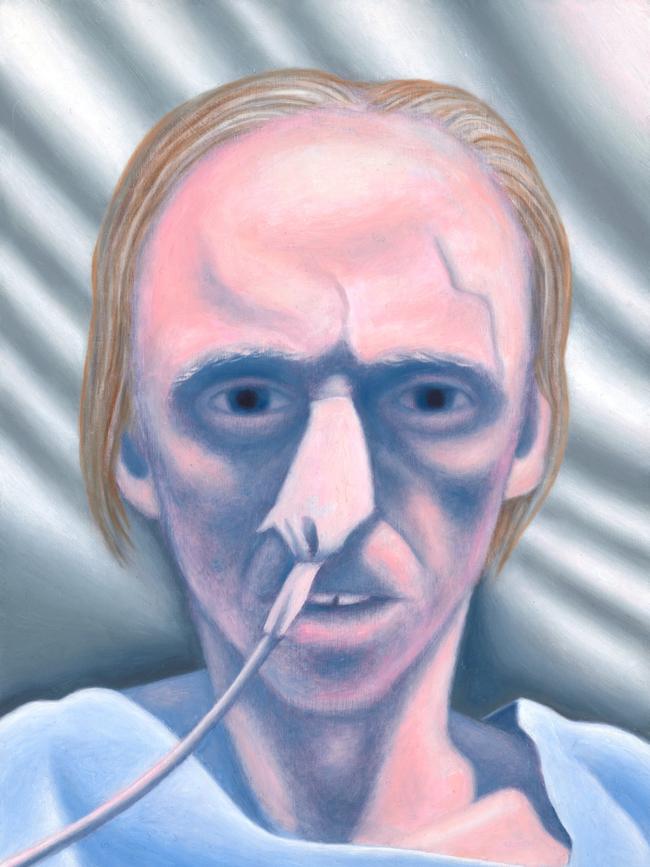

Another self-portrait by Chris O’Doherty (also known as Reg Mombassa) is a haunting image of the artist in hospital, with a breathing tube attached to his nose; the washed-out, pastel palette evokes depleted energy and suffering.

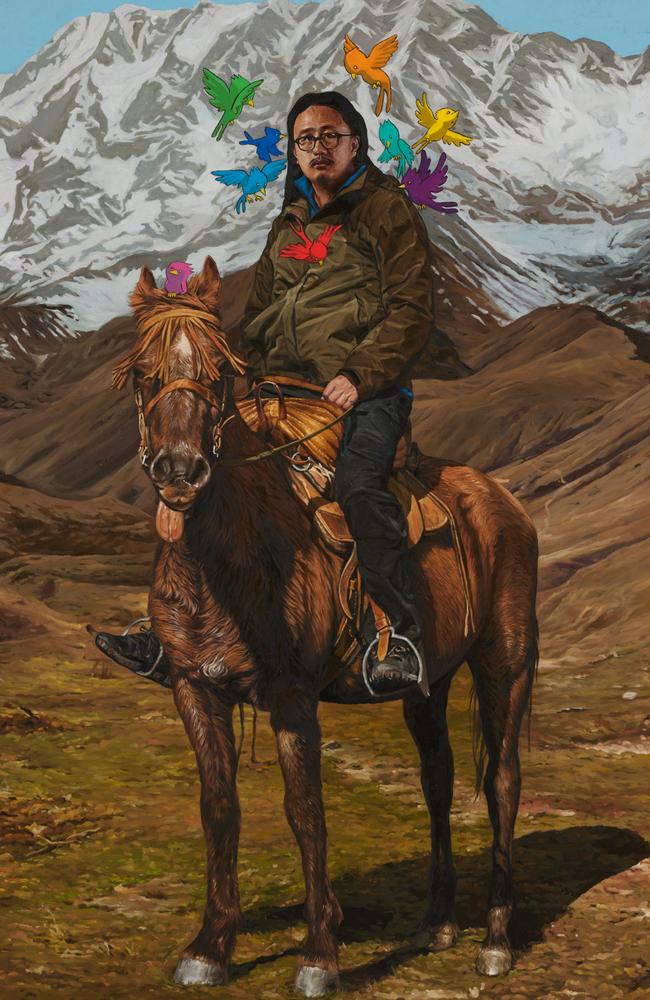

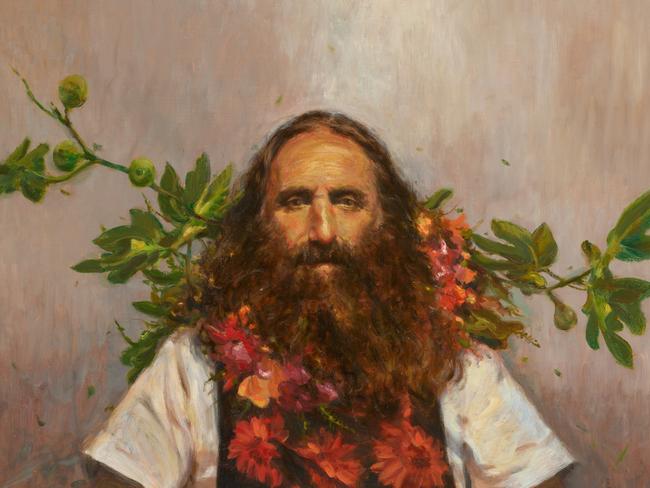

Evan Shipard’s portrait of Costa Georgiadis also echoes Duerer’s frontal pose, and is painted with both a visible pleasure in colour and a warm feeling for its subject.

Timothy Ferguson picks out a friend’s profile in striking chiaroscuro that, as he says, recalls baroque painters of the seventeenth century.

Callum Worsfold’s tiny self-portrait is attractively and freshly painted from life although the industrial mask he is wearing conceals much of the face.

David Fairbairn is represented by one of his spare monochrome pictures that are like homages to the style of Giacometti. Loribelle Spirovski’s finger painting of William Barton is quick and spontaneous.

At the opposite extreme, Marcus Wills has a large and arresting, though characteristically dark work that appears at first sight to be alluding to the myth of the flaying of Marsyas, but turns out to be a much more obscure story, obliquely linked to the father-and-son subjects of the picture.

The painting that stands out as the best in this year’s selection, however, is Peter Wegner’s portrait of barrister Sue Chrysanthou. The picture is modest in size and is free of all the gimmicks and the kitsch that weigh down so many others. Here nothing is superfluous, nor is anything omitted. Wegner’s portrait is still and yet strikingly, almost surprisingly alive. It is a demonstration of how the art of painting can be used effectively and above all economically to render a living and honest account of another human being.

Archibald Prize 2025 exhibition: May 10 – August 17, 2025, followed by the exhibition tour until 13 September 2026.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout