Why ‘independent’ RBA must avoid Canberra capture

At her post-meeting press conference, RBA governor Michele Bullock insisted the board “remains resolute” in its desire to return inflation to its 2-3 per cent target. Not, mind you, by the end of this year, but halfway through 2025.

The message to markets was clear. We are happy to tolerate 16 quarters of above-target inflation in the hope that unemployment does not rise too much. (And another year on top of that to get inflation to 2.5 per cent).

In light of Wednesday’s disastrous CPI result, which showed inflation rising to 4 per cent in the year to May from 3.6 per cent in the previous month, the credibility of this strategy has been dealt a serious, and perhaps fatal, blow.

The RBA board’s lack of resolve on inflation reminds me of the bad old days of monetary policy. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, central banks in Australia and overseas put full employment before price stability in the misguided Keynesian belief these objectives could be traded off.

They saw themselves as an arm of executive government and not separate from it. Arthur Burns, chairman of the US Federal Reserve from 1970 to 1978, was the poster child of this approach. His policy was to maintain an unemployment rate of 4 per cent, come what may. Jim Chalmers would have cheered him on.

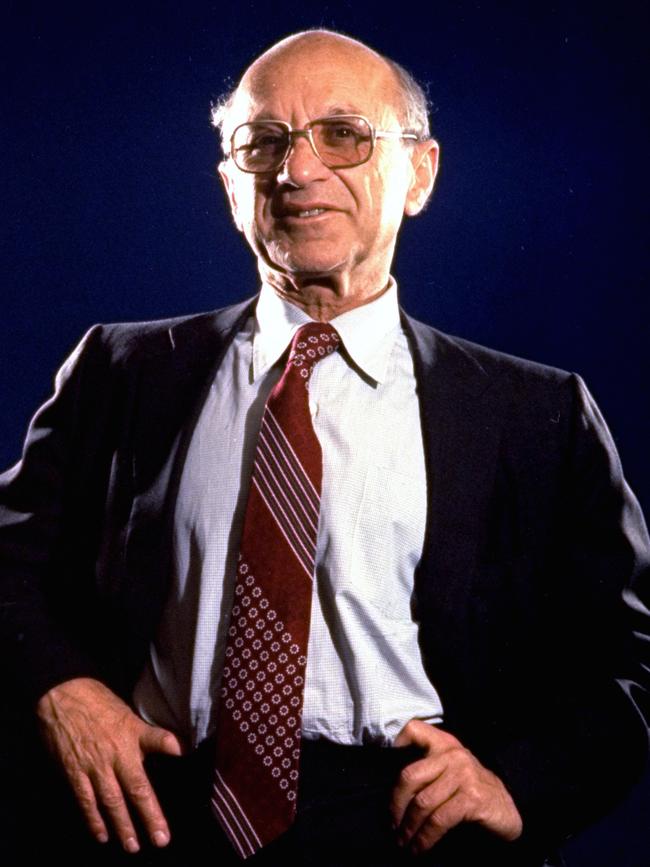

Milton Friedman debunked the Keynesian myths. He argued that, beyond the very short term, there was no trade-off between inflation and unemployment. He highlighted the role of expectations in fuelling inflation, which, once entrenched, could actually worsen unemployment and lead to stagflation.

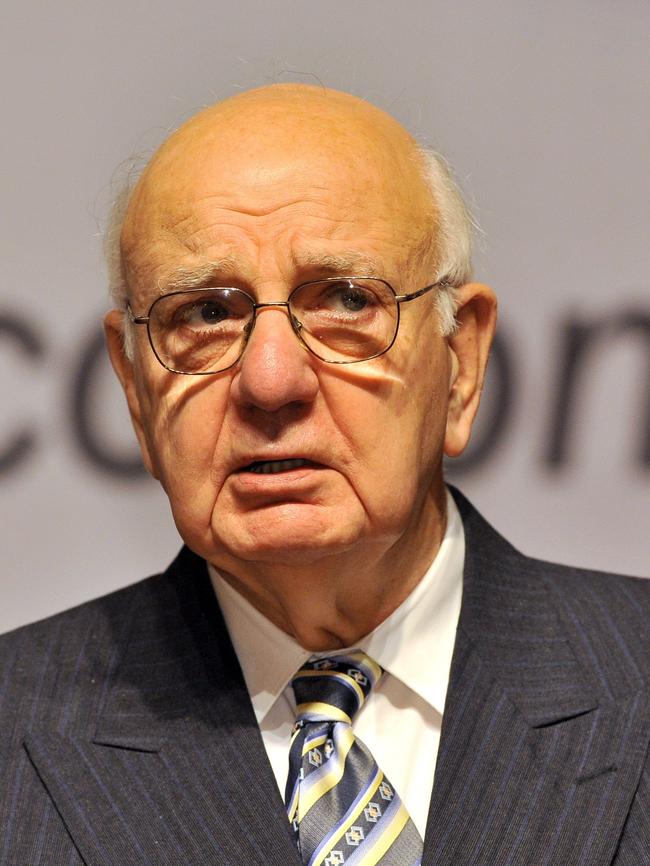

As we know, he was proved right. Inflation indeed became entrenched in the US and elsewhere, and it was left to Fed chairman Paul Volcker, who was the antithesis of Burns, to wring it out of the economy, raising the official rate to 20 per cent in 1981. Similar harsh medicine was necessary in Australia, at great economic and social cost.

Why invoke this history? Isn’t the modern RBA independent of government? Hasn’t it learnt from its mistakes in the past? Contrary to what we hear every day, within the public sector there is no such thing as independence from government. And certainly not for the RBA.

It is a creature of government, established by legislation; its riding instructions are set out in the statement on the conduct of monetary policy the board issues jointly with the treasurer; the government appoints the board’s members. Indeed, the Treasury secretary, the treasurer’s chief economic adviser, sits on the RBA board as a full voting member: an arrangement you will not see in any credible OECD country or defended by any monetary policy governance expert.

When people talk about independence, they mean that the RBA board makes its decisions at arm’s length from the government. These are not, as they were in earlier eras, directed by the treasurer. The fact the government cannot unilaterally sack the governor before their seven-year term is up is another layer of protection. But this doesn’t mean governments do not seek to influence governors and monetary policy decisions. How can they not, when an ill-timed interest rate increase can derail their re-election prospects?

During its time in office, the Albanese government has: excoriated former RBA governor Phil Lowe for raising rates in 2022; accepted radical recommendations from the RBA review that, as former RBA governor Ian Macfarlane has pointed out, will drastically weaken the authority of the governor and the bank, and; in the statement on the conduct of monetary policy, given full employment far more prominence than inflation.

Jim Chalmers’ emotive and irresponsible language has not helped, characterising policies that might restrict excess demand as “smashing” and “hammering” the economy.

While none of these factors, taken in isolation, is likely to affect monetary policy decision-making, there is no doubt, considered together, they are exerting unwelcome pressure on the RBA and Bullock. In her public comments on the irresponsible federal budget, Bullock has tied herself in knots to avoid offending the Albanese government.

But the RBA is not entirely blameless. Bullock’s repeated references to negotiating a “narrow path” to bring down inflation suggest, wrongly, that the economic terrain is clearly defined and can be negotiated with skill and care. This has never been true, least of all in today’s economy.

Since the pandemic, we have been hit by a series of complex demand and supply shocks that central bank forecasters have not only failed to anticipate, but did not fully recognise as they occurred. Indeed, current Australian developments are puzzling economists: our surprisingly resilient household sector and labour market despite 13 cash rate increases since 2022, but on the other hand output growth and productivity slowing to a crawl, the latter risking wage-driven inflation even as nominal wage growth moderates.

Rather than wishing for the best, the RBA board would be better served to think about the two worst-case scenarios it faces. One, taking the cash rate too high, which could cause short-term unemployment to spike more than the government wants to see. Or two, leaving the cash rate too low and allowing inflation, and inflationary expectations, to become entrenched.

The first scenario might trigger a short recession, which a future lowering of rates (and increased fiscal support) could end. But the second one would damage the RBA’s inflation-fighting credibility, risking much higher interest rates and a deeper and longer recession. While no-one wants to see higher unemployment, these risks are not symmetric.

In her heart Bullock knows what needs to be done. The RBA board’s August meeting looms as her moment of truth. For the sake of the country, let’s hope she tunes out the pressure from the government in the lead-up to the election. I’m sure she does not want to be remembered as Australia’s Arthur Burns.

David Pearl is a former Treasury assistant secretary.

There is a fine line between prudent caution and dangerous irresolution. While the Reserve Bank of Australia board did not cross it at its meeting last week, it was getting perilously close.