Watering down draft demeans spirit of the voice

The draft amendment is already modest, derived from drafting conceived with constitutional conservatives. The original 2014 drafting created three constitutional guarantees.

First, it required parliament to establish an Indigenous body to advise it and the executive on Indigenous affairs, and gave parliament power to determine all aspects of the body. Second, it required advice to be tabled in parliament. Third, it required the Houses to consider the advice when debating proposed laws with respect to Indigenous peoples.

Its conservative co-creators, including Julian Leeser, Greg Craven, Damien Freeman and Anne Twomey, were satisfied this drafting respected parliamentary supremacy and upheld the Constitution.

Various iterations evolved in intervening years. The tabling procedure was dropped. The requirement for parliamentarians to consider the advice was dropped. The draft wording released at Garma was more modest than the 2014 drafting.

Those claiming it has been radicalised, or that advice to the executive is new, are incorrect.

Inflated concerns about potential litigation regarding advice to the executive should be understood in context. This is hype about mere consideration of advice. There is no suggestion of potential litigation regarding advice to the parliament. All agree no laws could be invalidated and parliamentary supremacy is fully respected.

While I have suggested inserting “proposed laws” to further signpost non-justiciability, most experts say this is unnecessary because non-justiciability is already clear.

This new panic around constitutionally mandated advice to the executive is not about whether a court might require a bureaucrat to implement the voice’s advice. It concerns only whether a court might tell an executive decision maker to consider the voice’s advice regarding Indigenous communities. Not follow it. Just consider it.

A possible requirement to consider the voice’s advice has been overblown. There is nothing in the current drafting that requires policymakers to consider the advice. It is for parliament to articulate procedures for policymakers to receive and hopefully consider advice in a way that improves decision-making.

Parliament could confine or preclude obligations to consider advice under the current drafting. But why would it? The whole point of a constitutionally guaranteed voice is for partnership with Indigenous communities to become ordinary practice in Indigenous policymaking – an embedded part of political culture.

Former chief justice Robert French wrote in this newspaper that it was “improbable” that a court would compel an executive decision maker to “take into account” the voice’s representations.

On the very remote possibility of a successful court challenge, the only result is the court might tell them to consider the advice. Not follow it. Just consider it. This still upholds parliamentary supremacy and keeps government in charge.

The Attorney-General’s suggestion that the drafting be changed to make it even clearer that parliament can remove any expectation that advice should be merely considered by government, should be rejected. The government should not scramble to appease fearmongers making exaggerated claims.

The suggested change would not just make it even more abundantly clear that parliament has power to remove any obligation that policymakers even consider the voice’s advice (a power it has under current drafting) – it also invites future parliaments to use this power to curtail the voice’s influence. Over-emphasising parliament’s power to curtail the “legal effects” of the voice’s representations basically says: “Hey politicians, you can legislate to undermine the voice if you like, maybe you should?”

This demeans the spirit of the proposal. Inserting such a prompt would lead to bad faith dealings, providing an explicit and permanent reminder to politicians that they can – and perhaps should – legislate to curtail the basic respect and dignity accorded to the voice.

Indigenous leaders are right to reject panicked attempts to appease fearmongers – all over whether the voice’s advice should even be considered by policymakers.

Of course, it should be considered. That is the whole point.

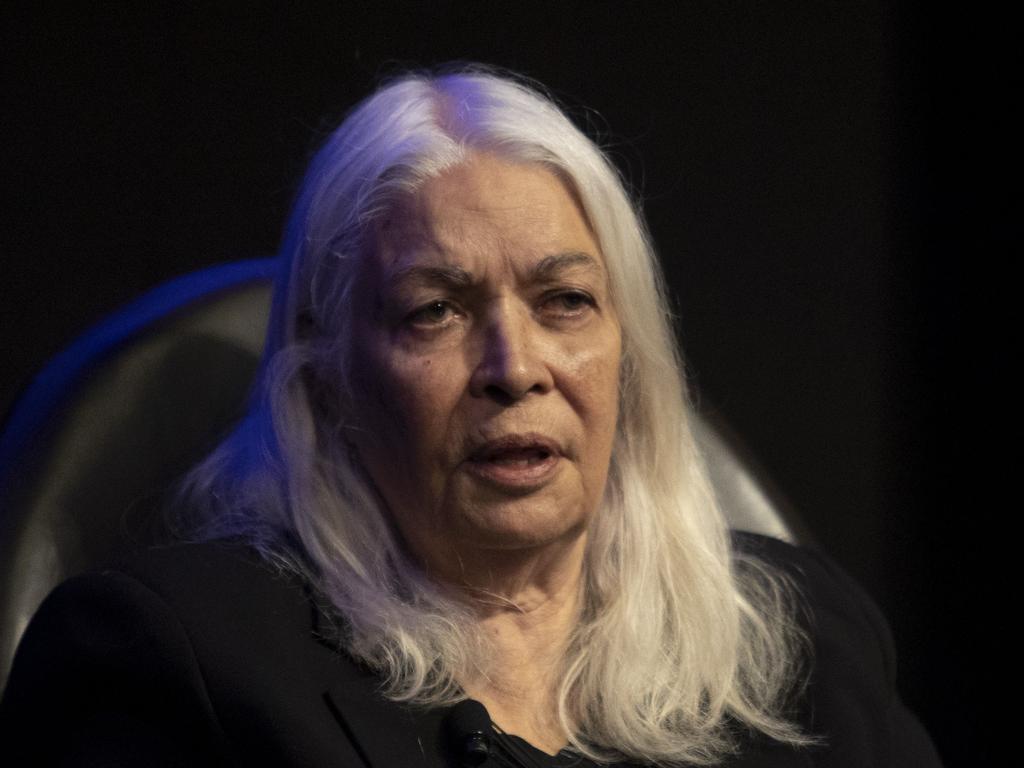

Shireen Morris is director of the Radical Centre Reform Lab at Macquarie University Law School

The government should not weaken the voice drafting to appease exaggerated concerns. The Attorney-General’s suggested change would short-change Indigenous people and invite future bad faith efforts to undermine the voice.