Want a voice? It should be a simple Yes or No

Almost every day for the past fortnight, The Australian has been airing well-argued opinion on whether the electorate requires more detail on the proposed Indigenous voice to parliament before we are asked to vote Yes or No in a referendum.

The flurry of debate, a necessary and welcome feature of democratic decision-making, was triggered by an interview with Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney in which she indicated the government’s intention to simply ask the population if it was in favour of the voice.

Reflecting on the failure of the most recent referendum in 1999, which asked Australians whether the nation should become a republic, she said: “The (1999) debate was around the model, not whether or not we should be a republic. I want to avoid that in this referendum. It’s really important that the question be about whether there should be a voice, not about what sort of voice it will be.”

I am in full agreement, and each subsequent opinion article or interview I’ve read in these pages – both for and against – has only reinforced my support of the government’s plan to keep it simple.

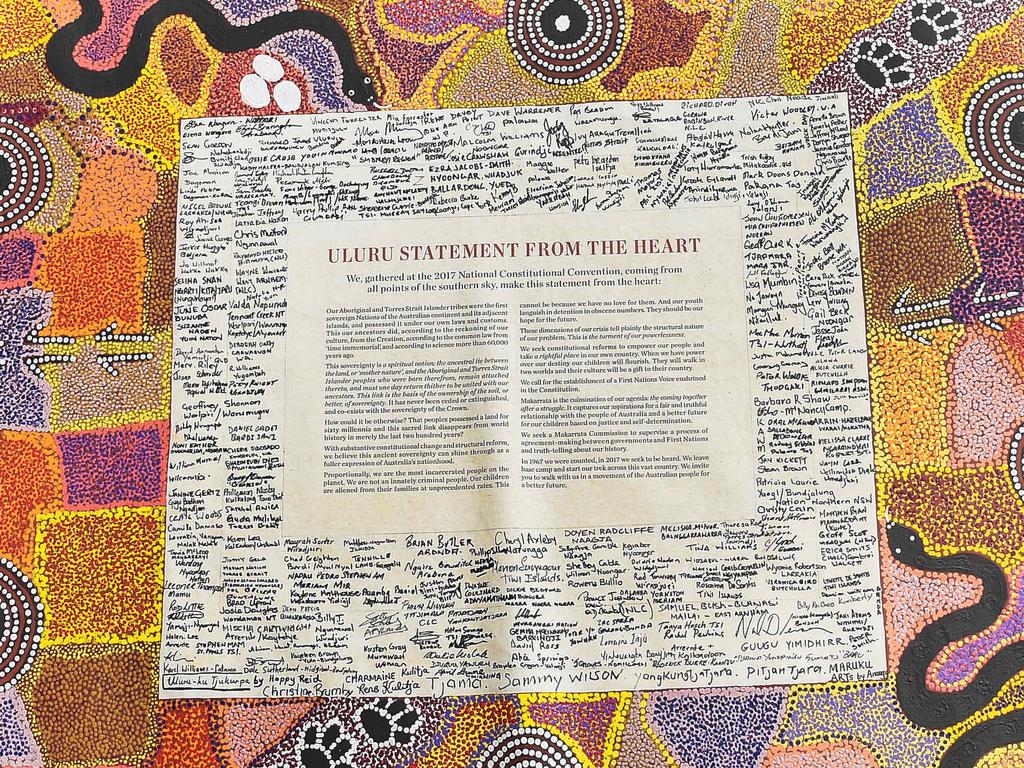

Let’s start with the piece by Megan Davis from last week’s Weekend Australian, in which she describes the historically significant consultation process with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that culminated in the Uluru Statement from the Heart. There are many valuable insights in the article but, focusing on whether we need more detail on the voice before proceeding to a referendum, Davis explains why the argument is a furphy.

During the past five years, the concept of an advisory body that gives Indigenous Australians a say on laws and government policies that affect their lives has been developed and tested across three highly visible (and costly) national processes:

• The regional dialogues and First Nations Constitutional Convention that delivered the Uluru statement.

• The joint select committee inquiry co-chaired by Labor’s Patrick Dodson and the Liberals’ Julian Leeser.

• The Indigenous voice co-design process overseen by former minister Ken Wyatt.

The Australian people, Davis writes, will not be asked to vote on a specific model of the voice because that detail should be left to federal parliament. The authors and advocates of the Uluru statement called for the voice to be enshrined in the Constitution in full knowledge that whatever model is established following a successful referendum would require adjustments by the parliament from time to time, as circumstances change.

Fred Chaney and Bill Gray have provided another thoughtful essay, explaining that while the government needed to demonstrate that the voice referendum would not be its sole focus in addressing “life and death” issues Indigenous communities faced, “it is important for the wider public to understand that it is not necessary to have a detailed or agreed model of a voice finalised or legislated before going to a referendum”.

Marcia Langton and Tom Calma, who co-chaired the panel overseen by Wyatt, see risks in going to a referendum without a fully formed model of how the voice would work. Langton is of the view that Indigenous Australians would prefer legislation for the voice to be tabled in parliament before the constitutional amendment is put to a vote.

No doubt Langton and Calma have been influenced by the concerns of people including newly elected parliamentarians Kerrynne Liddle and Jacinta Price, both of whom have told The Australian that they are concerned the focus on the voice will distract the government from more urgent challenges on the ground.

But the reality, neatly encapsulated by commentator Troy Bramston, is that most politicians and commentators calling for the government to outline the advisory body in detail ahead of a referendum, including senators Liddle and Price, have always been opposed to it. Which is why the Prime Minister and Burney are determined to avoid the mistakes of the pro-republic campaigners in 1999.

The same point can be made of Henry Ergas who, writing in Friday’s The Australian, put forward an argument for the necessity of greater detail to avoid the High Court having to resolve “unending disputes”. Several of Australia’s most eminent constitutional lawyers have already affirmed that a constitutional amendment can be framed to allow for the establishment of a voice whose operation would be non-justiciable – as intended by its proponents from the start.

It’s true that in my submission to the joint select committee in March last year, I advised that an exposure draft for the voice should be developed in the final phase of the co-design process, though only passed subsequent to a successful referendum.

Noel Pearson made a similar suggestion at the time, requoted in last Tuesday’s editorial: “Let us complete the legislative design of the voice, and produce an exposure draft of the bill so that all parliamentarians and the members of the Australian public can see exactly what the voice entails.”

But let’s be clear: Pearson and I were operating in a completely different political context when we advocated for legislation to be advanced. Conservatives in government were championing the notion that the voice should be established in legislation, rather than in the Constitution, and my rationale was to try to assist voice proponents in government to keep the option on the table.

With a new government and Prime Minister, brought to office with a clear mandate to take the question of an Indigenous voice to the people, the development of a more detailed model would lead to only one eventuality – a devastating No vote. Those who argue otherwise are, consciously or unconsciously, motivated by a desire to sabotage the process.

Mark Leibler is senior partner at Arnold Bloch Leibler. He co-chaired the Expert Panel and the Referendum Council on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.