Most politicians and commentators calling for the government to outline the advisory body in detail ahead of a referendum have always been opposed to it. They fundamentally misunderstand the Uluru Statement from the Heart. No voice to parliament will ever satisfy them. Trying to win them over risks a referendum they are unlikely to support.

The referendum should be about establishing a head of power in the Constitution that enables an Indigenous advisory body to be established. The Albanese government can, and should, outline a series of principles to guide the establishment of the voice but leave it to the parliament to determine how the advisory body should be instituted.

It may well be that in 10, 50 or 100 years the advisory body needs structural change. It may not be working as well as it could be. It may be that the Indigenous members of the advisory body suggest a different method of appointment or removal, want it to be larger or smaller or refocused in its work.

If a detailed model is enshrined in the Constitution, then it can be altered only by another referendum. This would be a cumbersome, expensive and risky process. A situation could arise where there is agreement among political leaders and Indigenous representatives that the advisory body should be changed but it fails at a referendum. Not establishing the final form of the advisory body before the referendum also deals with a key criticism put by those opposed to a voice: it would preserve and protect the sovereignty of the House of Representatives and the Senate. It means the Constitution would provide for a voice but the parliament would be able to determine its structure, composition and function.

Another danger in fixing the fine details before the referendum is it will attract critics who will argue it is still flawed. The referendum campaign would become a debate over the form of the voice rather than the principle of giving First Nations people a say in laws that affect them, such as those designed to address entrenched disadvantage by closing the gap on health, housing, education, employment, justice and safety.

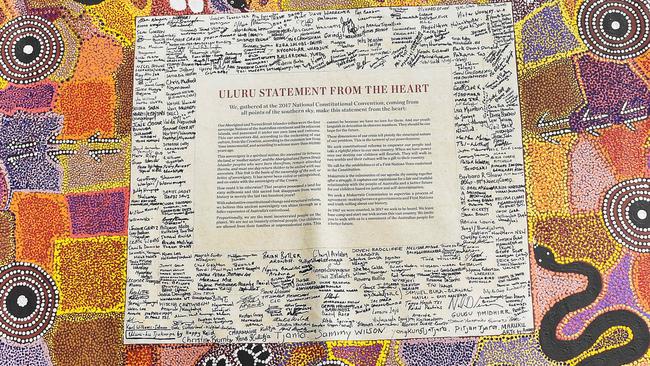

This is the spirit of the Uluru statement that in May 2017 invited Australians to walk together on a journey of reconciliation. It asked for the establishment of a representative Indigenous body that would advise the parliament on laws, policies and programs that affect Indigenous people and to enshrine this voice to parliament in the Constitution. It is not a revolutionary concept.

It is why the Uluru statement has majority public support according to opinion polls, and the backing of business organisations, trade unions, churches and faith groups, civic, sporting and charitable organisations and the legal community. It also has the support of every state and territory government, whether Labor, Liberal or Coalition.

Megan Davis, the Balnaves chair in constitutional law at the University of NSW and co-chair of the Uluru Dialogue, explained in The Weekend Australian (“A voice of recognition”, July 16-17) that the journey towards a referendum began over a decade ago with many processes of consultation and multiple reports published. The voice has been developed over “three key processes” since 2017.

“The idea that there is no meat on the bones of what a voice might look like is a furphy,” Davis wrote. “We can draw from the three processes a set of shared design principles for the formation and operation of the voice and a process that draws together best-practice engagement with our communities. This process should immediately follow a successful referendum so as to finalise the model according to a timetable set out in legislation.”

This is a compelling argument. “Legislation never precedes the power,” Davis adds. “No constitutionally mandated institution exists where the legislation has preceded the creation of the power. All institutions created by a power have been constitutionally mandated. Why is this the one exercise of a power whereby the institution will be created before the power?”

The other furphy, as Anthony Albanese said to me a few weeks ago, is that a consensus is needed before putting a referendum. This was the Scott Morrison position. “You don’t need a consensus but you need a broad agreement,” the Prime Minister said. “Firstly, among First Nations leaders and then, secondly, you would seek to get as broad a political agreement as possible for a referendum.” He will not grant the Coalition, which is unlikely to formally support the referendum, an effective veto.

The same critics who attacked Albanese’s referendum position have attacked the voice, echoing the past three Liberal prime ministers who wrongly labelled it as a “third chamber”. They claim the Indigenous advisory body would have an effective veto on the parliament when in truth it would have no legal or constitutional authority to override parliament.

The Uluru statement provides symbolic and practical reconciliation and recognition. It acknowledges and empowers Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with an advisory body that is formulated in legislation and subject to the parliament but enshrined in the Constitution. And it strengthens parliament’s mandate by providing a voice in the laws and policies that directly affect them.

Those who support recognition of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, their ancient history, culture and tradition with a First Nations voice to parliament in the Constitution must guard against those who not only wrongly dismissed it as a “third chamber” but who are demanding that a detailed model be agreed before a referendum is held.