Uni leaders must stand up for Jewish students

In recent weeks, a good deal of what I’ve been reading and hearing is focused on the unfolding drama in our universities, a spectacle I observe through an assortment of personal and professional lenses.

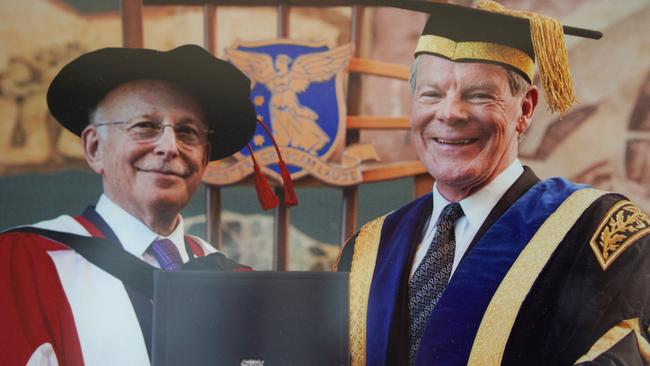

Let me begin with Melbourne University, the university where, almost half a century ago, I graduated with first-class honours. The university that, when awarding me its highest individual honour, the degree of Doctor of Laws honoris causa in 2014, specifically recognised my close connections with Israel, including my involvement with the Jewish Agency for Israel and the University of Tel Aviv. The university where, for the past seven years, I have served as a member of the governing body, the University of Melbourne Council.

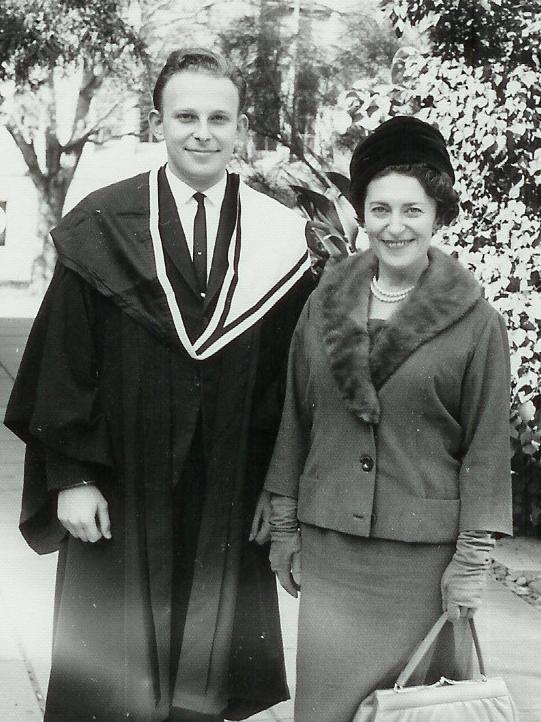

I’ll never forget the feeling I had, entering the law building for the first time in 1962. I immediately felt as at home as I did at the Jewish day school I had attended since the age of five.

I was born at the height of the Holocaust in 1943, and Melbourne University was my entry into the real world. As a somewhat rebellious school student, who didn’t like being told what to do, it was liberating to be encouraged to make decisions for myself, to think rationally about the way the world worked.

From Melbourne, I went on to do a masters degree at Yale – it was my first time out of Australia and everything about the Ivy League university intoxicated me. The atmosphere of deep inquiry and learning in which I thrived, the brilliant lecturers and dazzling intelligence of my fellow students.

These experiences informed who I became, who I am, and it breaks my heart to contemplate the disconnect between my experience of university life and that of Jewish students in Australia and the United States today.

During my undergraduate days, I was president of the Melbourne University Jewish Students Society, and at Yale I was fully engaged in Jewish and Zionist activities on campus. Like the overwhelming majority of Jews, Israel has been central to my Jewish identity since my childhood. I am a proud Zionist, not only because I support self-determination for the Jewish people in our ancestral homeland. I am also a Zionist because, along with 90 per cent of Jewish Australians, I believe Israel is central to our identity and survival as a people who have endured persecution and exile from host nations over millennia.

So, when Jewish students and staff at Monash University, an institution named after the illustrious general and first honorary president of the Zionist Federation of Australia, Sir John Monash, view a sign that says “Zionists not welcome”, they take it for what it really means – “Jews not welcome”.

When pro-Palestinian protesters in Brisbane and Canberra express their grievances against the Israeli government by mimicking Nazi gestures or expressing support for the murderous actions of Hamas, there is no doubt where they stand.

When they call for an intifada – the term defined in any dictionary as a violent uprising and a reference to the waves of suicide bombings and other attacks against Israelis in recent decades – it is, as the Prime Minister has confirmed, a call for violence.

The Prime Minister has also understood and publicly communicated that there is no ambiguity around the meaning of the most commonly used slogan by campus protesters. He has rightly identified the chant “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” – a call drawn straight from the Hamas charter for the annihilation of Israel and thereby inconsistent with a two-state solution – as a statement liable to incite violence.

The Prime Minister demonstrated moral clarity in calling out these slogans for what they are. And in response to powerful and principled commentary over the weekend by the chancellor of the University of Western Sydney, Jennifer Westacott, who publicly named and condemned the anti-Semitism being tolerated across our universities in the name of “free speech”, a number of other university leaders have followed suit.

And I ask myself how is it possible that, even after our Prime Minister has acknowledged there is a specific anti-Semitism crisis on campuses in this country, the chancellor of the university where I serve refuses to admit it, as others have.

From my experience, senior leaders at Melbourne University, who have been dealing with Jewish students at the coalface, have been both sensitive and empathetic, which makes chancellor Jane Hansen’s refusal to publicly recognise that there is an anti-Semitism crisis taking place on our campus all the more surprising and disheartening. Again, from my own direct experience speaking with students and staff, there is not a shadow of a doubt that we have a serious problem.

For Ms Hansen to suggest in her comments to The Australian that criticising or even questioning fellow chancellors on their handling of anti-Semitism amounts to “looking for division” is completely unacceptable.

I have communicated this to Ms Hansen personally and believe it is incumbent upon me as a member of the council to also say so publicly in the interests of the university, its reputation and high standing internationally. I urge others to do the same.

This is not an issue unique to any particular university. In the midst of this crisis, our most senior vice-chancellors saw fit last week to attempt to shift responsibility to the Attorney-General. Vice-chancellors Mark Scott and Peter Høj wrote to Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus on behalf of the Group of Eight seeking clarification around their legal position to respond to campus protesters.

Jewish students are crying out for support from their universities, and it is the responsibility of university leaders to ensure these places of learning are safe for all students. They can do so, as Jennifer Westacott and others have done, without seeking legal advice, but simply by speaking out and enforcing their existing policies.

Freedom of speech is critical, but where it amounts to bullying, intimidation or making the university an unsafe space for staff and students, serious disciplinary action is mandatory.

I call on all university leaders and government ministers to follow the Prime Minister’s lead and clearly and explicitly call out the hate speech and intimidation on campus, and enforce relevant university policies and codes of conduct. It goes to the heart of whether future generations of Australian students have the opportunity to learn and flourish as I did in a safe and affirming environment.

Right now, this is not an opportunity available to Jewish students and any other student who refuses to submit to the extreme rhetoric of these protesters.

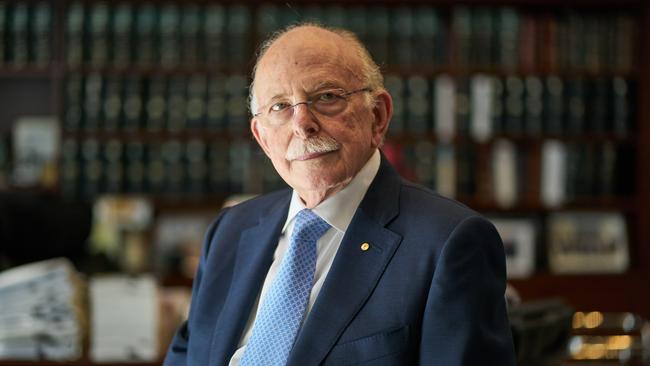

Mark Leibler is senior partner at Arnold Bloch Leibler. He writes in his personal capacity.

Over the past seven months, it’s fair to say my life has been consumed by the impact of the October 7 attacks by Hamas and the subsequent war in Gaza.