The Australian Electoral Commission struck 153,586 deceased voters off the electoral roll last year.

With the average age of death being 81, the sad truth for the Coalition is that most travellers who journey to that undiscovered country from which no voter returns are probably conservative.

So, while there is no single explanation for the loss of more than one million first-preference Coalition votes in the past six years, one reason is that 5 per cent of Scott Morrison’s supporters in 2019 have passed on.

Many Labor voters have also marked their final ballot paper, but we must assume they have been replaced in roughly equal numbers by new voters, since Labor is no more or less popular now than it was on the night Bill Shorten conceded defeat.

Political commentators declared Shorten’s 34.7 per cent of the primary vote to be a disaster. The same result in 2025 is hailed a triumph.

The unmistakeable conclusion is that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese did not win his landslide because Australians flocked to Labor. It was a gift from the Liberal Party, which forfeited the right to govern because it failed to inspire voters.

The starting point for the Liberals’ inquiry into this month’s disaster is not whether the party should move notionally left or right. If the party is forced to choose between meeting the moral expectations of teal voters or talking common sense to the masses, it can kiss goodbye to its chances of forming government.

Worse would be the Goldilocks option, neither hot nor cold. If Sussan Ley needs to know how that strategy works out, she should pick up the phone and call Morrison or Peter Dutton. A risk-averse campaign in 2028 will be the riskiest approach of all.

The inquest must begin with a search party to find the lost tribe of Coalition voters who have lived to tell the tale.

The bad news for the Liberals is that the party has not just lost ground in wealthier inner metropolitan seats. It is in trouble almost everywhere.

Voters who have turned their backs on the Coalition arrived at polling booths in Ford Rangers as well as Teslas.

They include nice people who voted yes to the voice to parliament and those who didn’t.

The Liberal Party and LNP also lost ground in the mortgage belt, a remarkable feat after 12 rate rises under Labor.

The descendants of Robert Menzies’ nation of homeowners turned their backs on the party he created.

Primary votes fell by 19 per cent in outer metropolitan seats, 8 per cent in provincial seats, and 12 per cent in rural seats.

The bottom line is that one in six of the 6.5 million voters who put Coalition candidates first in 2019 has walked away.

The Coalition’s voter deficit is even worse than that since the number of enrolled voters has risen by 10 per cent.

To win over new voters, it will have to improve its appeal to younger generations, women, and immigrants. Every incoming Coalition leader has been acutely aware of this challenge since the Howard era, yet none have managed to rise.

Over to you, Sussan Ley.

The Opposition Leader must also win back the Coalition’s lost base, many of whom are older and see the world very differently from the mashed avocado-munching upstarts they frequently deride.

Their economic circumstances are also very different, which will add to the political and fiscal challenges greeting the next shadow treasurer.

The teal movement, the political wing of the weather-dependent energy sector, is mistakenly accused of being the main reason for the Liberal Party’s decline. While it deserves its share of the credit for keeping the Coalition out of office, its impact on the decline in the Liberals’ primary vote is marginal.

Across the 10 former Liberal seats that have either fallen to teal independents or have been narrowly retained, the party’s primary vote fell by 91,000 between 2019 and 2025. Not all of those votes were lost to the teals.

Even if we add votes lost by the Liberals in teal try-hard seats such as Wannon and Dickson, the maximum total of the Coalition’s primary vote that has moved to teals is probably 200,000 at most, about half the number lost by natural attrition.

The Coalition’s primary vote has suffered far more from the resurgence of One Nation and other notionally conservative minor parties and independents. The primary vote for Pauline Hanson’s party in the lower house has more than doubled since 2019 to 984,000 votes.

The party has made significant inroads in metropolitan seats where its primary votes increased by 285,000.

Overall, the minor centre-right vote increased by more than half a million votes.

If we assume that three out of five of them are refugees from the Coalition, that could account for as much as a third of the Coalition’s lost tribe.

Here’s a back-of-the-envelope guesstimate of where the lost tribe has been wandering: more than three out of 10 have thrown in their lot with Hanson or other centre-right dissidents, fewer than two out of 10 have fallen for the teals or other woke brands, two out of 10 have fallen for the Trojan horse parties of the left such as the Animal Justice Party or Legalise Cannabis, or haven’t cast a regular vote.

Informal voters have noticeably increased in some key outer suburban seats the Coalition must hold or win, including Banks, Lindsay, Werriwa and Calwell. Three out of 10 have died.

Ley’s seat centres on Albury, a place of pilgrimage for Liberal tragics who know their history.

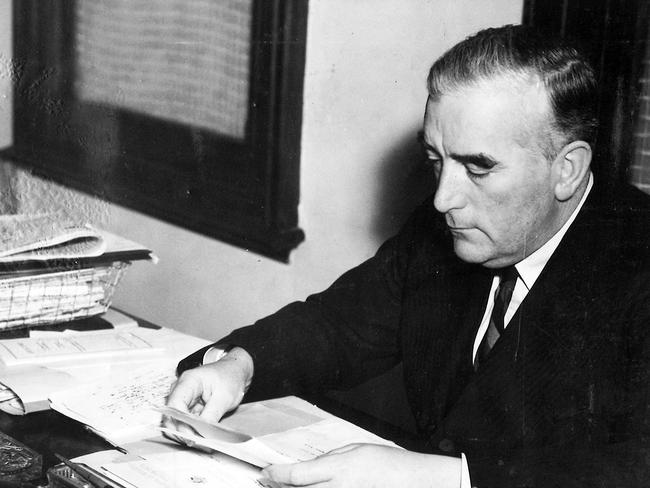

In December 1944, in a humble room above a department store, Menzies gathered the tribes from the Balkanised centre right for the first formal meeting of the newly formed Liberal Party.

Together with its reliable Coalition partner, the Liberal Party has formed government for 51 of the past 79 years.

Ley’s task is to put the ugly factionalism of the past two weeks behind her and project a vision for the future rooted in Liberal principles and shaped by the lessons of recent years.

There can be no more demanding job in politics right now, nor one more important.

Nick Cater is a senior fellow at the Menzies Research Centre.