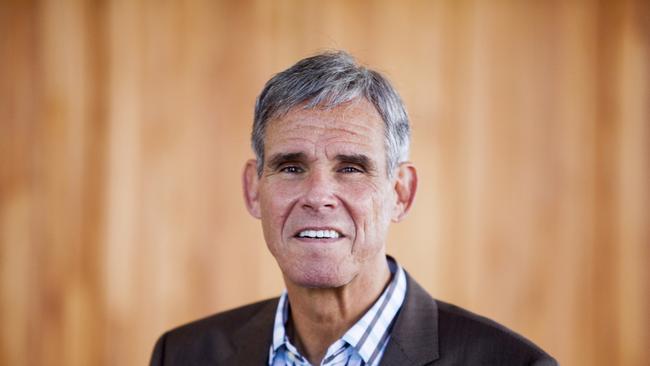

Front row seat to my future: looking at my dad is a mirror to my old age

Everyone says me and my dad are doppelgangers. If I age like him, that would be fine with me.

Mr dear 87-year-old father and I bear an unmistakeable physical resemblance that has grown stronger in recent years.

Which makes sense, given he’s my father, but it’s a phenomenon that has become more pronounced as I’ve aged. Gosh, people say, you look like your father. Or I’m referred to as his “spitting image”, which is usually accompanied by a sweep of the eyes from head to toe.

At some point in life we start noticing things we say or do as moments that carry a deep-seated shock of recognition; a phrase, an act, a physical tic that we recognised is precisely the sort of thing our mother or father might do.

We reject that. We wave it off with a shake of the head. For some, it’s a horrifying thought.

But as Dad and I have aged, an inescapable paradigm has come into play. As bleedin’ obvious as it sounds, the child who looks strongly like a parent, the likeness eerily sharpening as they age, has a front-row seat to their own future.

Bluntly, those children get to see how they get older. How they may look at 60, 70, 80 and beyond.

This is the “oh my goodness I’m turning into my mother/father” refrain to the factor of 100.

I visited my father in his retirement village recently and we sat facing each other in the in-house cafe. We had coffee and toasted sandwiches. In that moment I understood with grand force that I was looking at myself in a quarter-century’s time.

He shared amusing stories from his past, current health concerns, his continuing wrestle with modern technology, particularly his phone and his obsession with getting things “off” the internet. He finds that the World Wide Web is messy and should be tidier, like pristine business ledgers and things he couldn’t delete infuriated his sense of order. Buzzed like flies in the recesses of his brain.

Meanwhile, I was mesmerised by myself who was pushing 90 on the other side of the table, across the cups and saucers and cutlery. I admired some things and grimaced at others. I marvelled at the unpredictable nature of male eyebrows and ear hair.

Overall, I concluded that my Dad was in pretty good nick despite his declining mobility issues. I drilled him about his most recent visit to the doctor. What did he say about your diet? You’ve lost too much weight too quickly I said, suddenly becoming his medical adviser and life coach.

“He said I need to eat more protein,” my father said. “Eggs for breakfast.”

“EGGS!” I said a little too enthusiastically. “Exactly. Good idea. Absolutely. Eggs! Eggs in the morning. You MUST start having eggs every day! Have you got any in the fridge right now?”

The waitresses, concerned, were looking over. A tiff? Was this elder abuse? Egg abuse?

Weirdly, I was not just concerned in this instant about my father ageing well. I was barracking on my future self. Protein! Eggs!

“I don’t feel very hungry lately,” he said.

“Here!” I said, plonking a little goodies bag I’d brought for him. Cheese. Crackers. Shortbread. Chocolate. “Here! Cheese. Cheese is excellent for you. For the bones. Who doesn’t like cheese? You must eat. Have some now.”

Other residents of the retirement village started wandering in for an early lunch. Some were gloriously robust, straight-of-back, purposeful, their minds busy. A few looked like their internal organs might have been constructed out of barbed wire. Others were hunched over walkers, pushing on, willing their fragile selves towards a roast lamb Sunday dinner.

I wondered if this whole ageing thing wasn’t some perverse, predestined, universal roll of the dice. Good genes. Dud genes. Minds of steel or rusted tin. Eyes up or eyes down.

Weirdly, I was not just concerned in this instant about my father ageing well. I was barracking on my future self.

What I did know was that the matter of ageing is and always has been, an area of endless study, scientific striving and intense human scrutiny. It has been the subject of literature, art and song. It is the Wordle puzzle that has yet to be cracked in six lines.

And not for the want of trying.

A new book about the science of ageing – Super Agers: An Evidence-based Approach to Longevity by molecular scientist and cardiologist Dr Eric Topol – just might tip on its head everything we thought we knew about getting old.

“About two decades ago, a California research team observed a striking phenomenon: while a majority of older adults have at least two chronic diseases, some people reach their 80s without major illness,” The New York Times reported this month upon the book’s publication. “The researchers suspected the key to healthier ageing was genetic. But after sequencing the genomes of 1,400 of these ageing outliers – a cohort they called ‘Wellderly’ – they found almost no difference in their biological makeup and that of their peers. They were, however, more physically active, more social and typically better educated than the general public.”

The ongoing Wellderly Study, as it became known, published initial findings in the scientific journal “Cell” in 2016, suggesting “a possible link between long-term cognitive health and protection from chronic diseases, including cancer, heart disease and diabetes, which account for 90 percent of all deaths in the United States….”

Was “cognitive health” the key? Dr Topol reportedly said the fact that genes might not dictate how we age was “liberating”, and opened the possibility that human beings could “do better” to delay disease.

Given the most typical diseases associated with ageing – Alzheimer’s, diabetes, cancer – can develop over decades, Dr Topol argued that surely this gave everybody a “long runway” to work out how to fight the very things that could prematurely bring them down.

The cynic might say – here’s another book on trying to age well to add to an already voluminous pile.

But the key planks of Dr Topol’s argument are difficult to ignore.

Taking up “strength training,” he writes, or arguably any physical activity, can dramatically reduce disease risk.

So can a decent night’s sleep, particularly “deep sleep”. He suggests locking into a “consistent sleep schedule”.

Improving mental health was another major factor in ageing well. Get outdoors. Adopt an active social life. This was critical to lowering chronic disease risk.

Sitting opposite my doppelganger father in the retirement village cafe and perusing the other residents who wandered in and out in various states of wellness, I thought he was in pretty good shape at 87.

The brain was good. He had a nice flush to his cheeks. He told me about a themed evening he’d enjoyed recently in the village dining room. He was alert and the raconteur of old. If he was a used car, the only thing you’d look twice at were the tyres. He was not as quick on his feet as he once was but at that age, who is?

My goodness, yes, I was turning into my father. But on the current evidence, and with the long game in mind, that didn’t seem like such a bad thing after all.