Silence on details is already dooming the voice to failure

The problem is not malice, trickery or incompetence. It is the absolute refusal of the Albanese government to provide details for the voice. The red lights are flashing clearly. Statistically, recent polls show support for the voice collapsing as the referendum slowly draws closer. This is typical of Australian referendums, but this early and for a referendum without detail it is catastrophic.

As a director of the pro-voice organisation Uphold and Recognise, I have been involved in numerous attempts to bring out wise, respected, moderate Australians in favour of the voice. Much less than a handful have agreed. The polite refusals are all the same. Eminent Australians will not back the voice until they know what it is.

Yet it seems a point of honour with the government that it would rather die than divulge, even if this takes the referendum with it.

This horror of detail is a terrible misreading of the failed republican referendum in 1999. Labor saw the republic mercilessly attacked on detail, so the voice referendum will be detail free. The government just cannot accept that any void of information will be filled with speculation, some of it genuinely confused, much imaginatively hostile. This assault began immediately the referendum was announced. Unfounded accusations of “third chambers” and “special rights” have followed the voice like stalking furies.

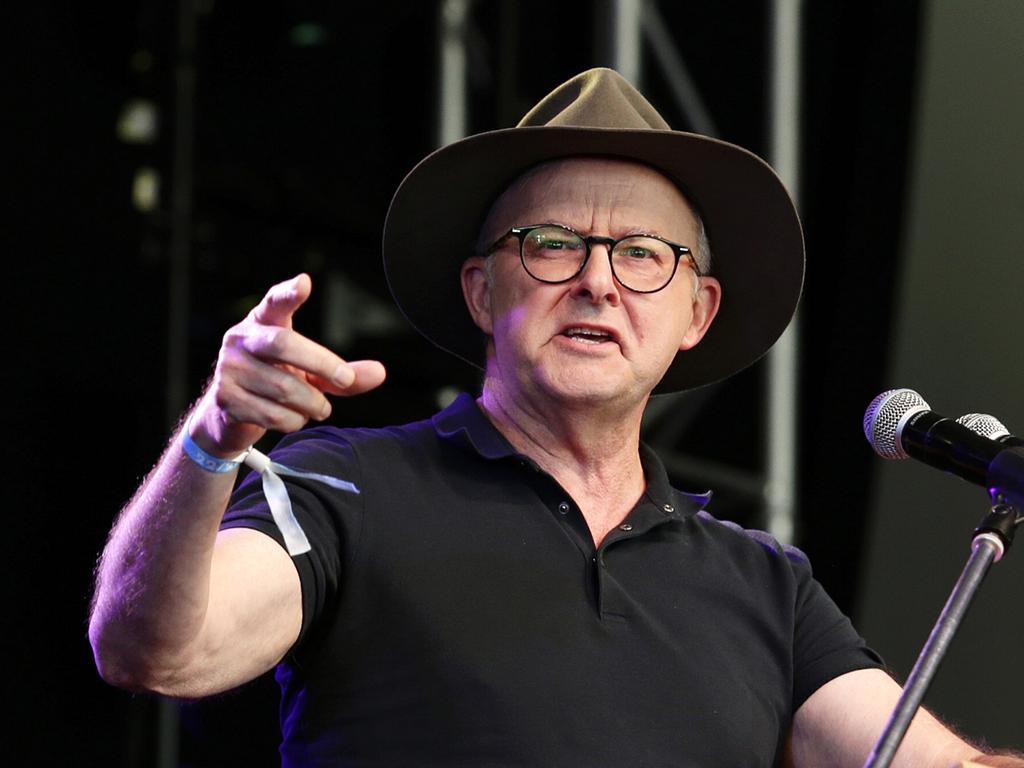

Yet Anthony Albanese remains steadfastly covert. He refers vaguely to the substantial report by Marcia Langton and Tom Calma, as well as “other reports”. But he has never promised to implement any of them. Last week there was excitement that he might have committed to something. He talked in an interview about a region-based voice of 20 Indigenous people. But it was just another noncommittal reference to Calma-Langton. So the government’s formal position is a constitutional lucky dip. You pay your money, stick your hand in the barrel and hope the prize is not a dud.

In these circumstances, it is grimly unsurprising the polls have turned on the voice. A few months ago, boosters were trumpeting figures of 75 or even 80 per cent approval, admittedly after fairly crude mathematical manipulation. Now support is down to about 50 per cent. The other half of the electorate is evenly divided between hard Nos and Undecideds.

Inevitably, a confusing and sometimes misleading campaign will result in most of the Undecideds voting against the voice. Just as depressing is the softness underlying approval of the voice. About a third of the Yes vote is a present inclination rather than a firm vote.

Yet another problem is that, as much as the Prime Minister says this referendum does not belong to him or Labor, it does. The polls show support for the voice overwhelmingly comes from Labor voters and other progressives. Support from conservatives is miserably thin. A bipartisan referendum this is not. But the knockout blow comes from electors demanding exactly the sort of detail Labor just will not give.

Only half those supporting the voice think they have enough information to vote. Undecided voters overwhelmingly demand more information. This is a train wreck willing itself to happen. But Labor’s refusal to elaborate is unflinching. Its only theoretical attempt to justify its ban on detail is an absolute proposition that with constitutional amendments you put the principle in the Constitution and leave the undisclosed guts for future legislation. This is not fair dealing with the public.

This is an unusual referendum. It creates a new, important institution. It does make drafting and practical sense to establish that institution in the Constitution, and leave structures, proceedings and details for parliamentary legislation. But that is no excuse for not informing the electorate of the broad shape of the institution before it is set in concrete. The lack of explanatory constitutional language makes it even more vital electors are fully briefed.

Sadly, schoolboy debating analogies abound. Who would buy a car without knowing its make or price? Who would buy a house without knowing its suburb and number of bedrooms?

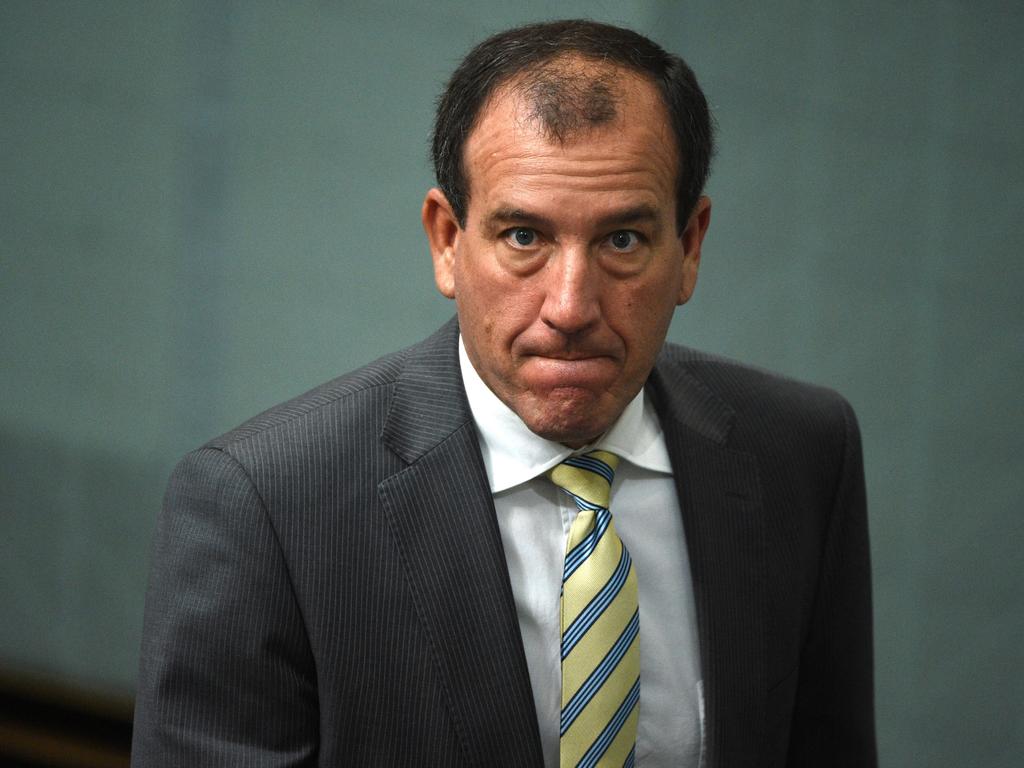

As the polls on the voice show, not many. This chronically subterranean approach to constitutional amendment needs to be critiqued within the invariable politics of referendums. To win, they must have bipartisan support. But no opposition can agree in advance to something they have never seen. Hence the frustration of Coalition voice supporters such as Julian Leeser, tasked with persuading his colleagues to the undisclosed.

The other assumption made by the government seems to be that, in the absence of public funding, there would not be a No case. The Yes case would be awash with donations from friendly corporations. This was utterly misconceived. No cases spontaneously generate around a referendum and easily attract media coverage. So far we have out there Tony Abbott, Jacinta Price, Pauline Hanson, Warren Mundine, the Nationals and (probably) Lidia Thorpe. Who are we waiting for, Bismarck?

When you read the 200-odd pages of the Calma-Langton report, and the preceding report of the parliamentary committee on constitutional recognition, tallying the questions that need at least preliminary answers from government is not difficult. What will be the name of the voice? Calma-Langton and Albanese sensibly go with “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples voice”. Some Indigenous radicals want the divisive “First Nations voice”. Which is it? How does someone get on to the voice? Will you be elected or appointed as a representative by local bodies? Calma-Langton wisely avoids the politics of election. So is this the idea? Which local bodies will feed into the national voice and keep it firmly grounded in Indigenous people and problems, and how? What government action will be scrutinised by the voice? The proposed draft says “matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”. But does this catch only specially connected matters or also general laws inevitably affecting Indigenous people?

Albanese apparently says general amendments to Medicare would not be caught. Is that right? Is it totally up to parliament when and whether it consults the voice, or are there some situations where parliament is obliged to consult? Calma-Langton says yes. What does the government think? Will the government stick with its draft amendment subjecting executive action to the consultation requirements of the voice? Rightly or wrongly, people will worry this could involve the judges. Is the worry worth the gain?

On the issue of the judges enforcing the voice, Calma-Langton wisely said they should not but did not offer a specific legal formula to prevent it. Some eminent lawyers do not think judicial intervention a realistic problem. But between genuine worry and conscious mischief, what (if anything) should or could be done about it? Again, Calma-Langton proposed that the voice would be kept away from loads of money and resources, so preventing the standard accusations of a new Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. Is this the idea? Every public body needs assurance. The ultimate assurance is sacking someone who acts inappropriately. Calma-Langton says only the voice should be able to sack one of its members. Is this a problem?

Finally, the sternest criticism is it will make no difference on the ground to real problems such as family violence, poor educational outcomes and appalling health. Have we considered putting legislative priorities over the voice requiring it to focus on these policy failures?

None of these questions is meant negatively. Each is a genuine query that reasonably can be asked by strong supporters of the voice to understand the proposal and to answer ill-willed criticism.

The difficulty is we have few answers to this questionnaire, other than ritual general references to Calma-Langton.

But there is nothing here that cannot be fixed. The government can resolve these questions and decisively inform an increasingly worried public. This is not about the proposed public education campaign. People cannot be educated once they have already made up their minds in a ringing silence. They need clear answers in advance, not podcasts. If these answers are not provided, we face our 37th failed referendum.

Greg Craven is a constitutional lawyer and a former vice-chancellor of the Australian Catholic University. He is a member of the federal government’s constitutional experts group. The views in this piece are his own.

The Indigenous voice has entered the slow, long death dive of Australian referendums. Unless it pulls out, it will crash and burn on polling day.