Judges make it a roll of the dice on voice

Both were written by longtime supporters of this constitutional innovation. And both share the characteristic of implicitly portraying opponents of this amendment as misinformed (or, worse, dealing in disinformation) or lacking the empathy and moral credentials of those who support it – people like them, in other words.

These are all variants of what is known as the ad hominem argument, where you play the man, not the ball, and ignore the substantive criticisms being made in favour of implicitly painting a Manichean world where supporters are good moral beings and their opponents bad or otherwise deficient.

So let me tell readers where the authors of these articles go off the rails and why I do not think those in favour have superior moral antennae than do we opponents of the voice.

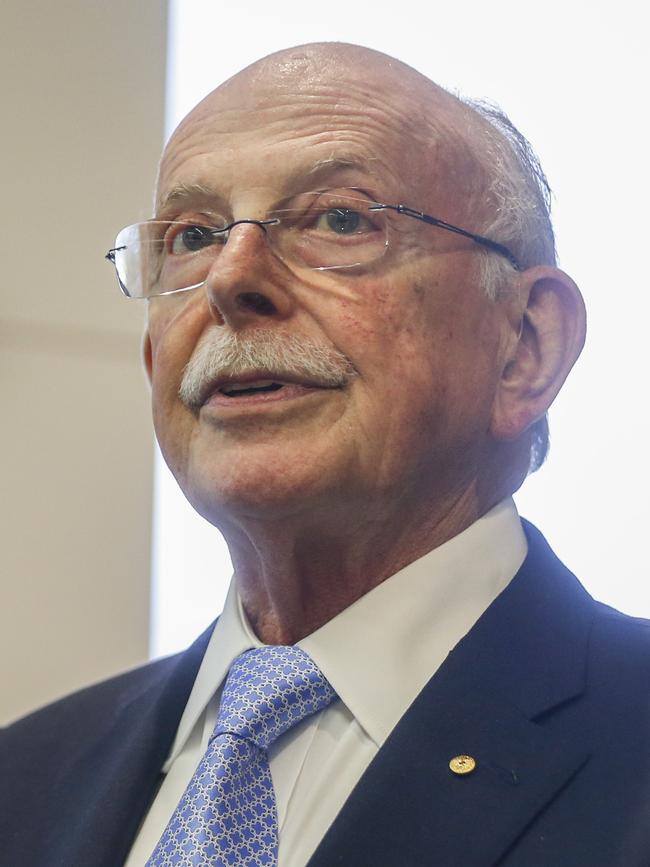

Start with the December 19 article by Mark Leibler. In it, he attacks the substantive criticisms made by Chris Merritt, Janet Albrechtsen and Ian Callinan (who Leibler omits to mention is a retired justice of the High Court of Australia). By clear implication, Leibler labels the views of all three as dealing in “misinformation” and “disinformation”.

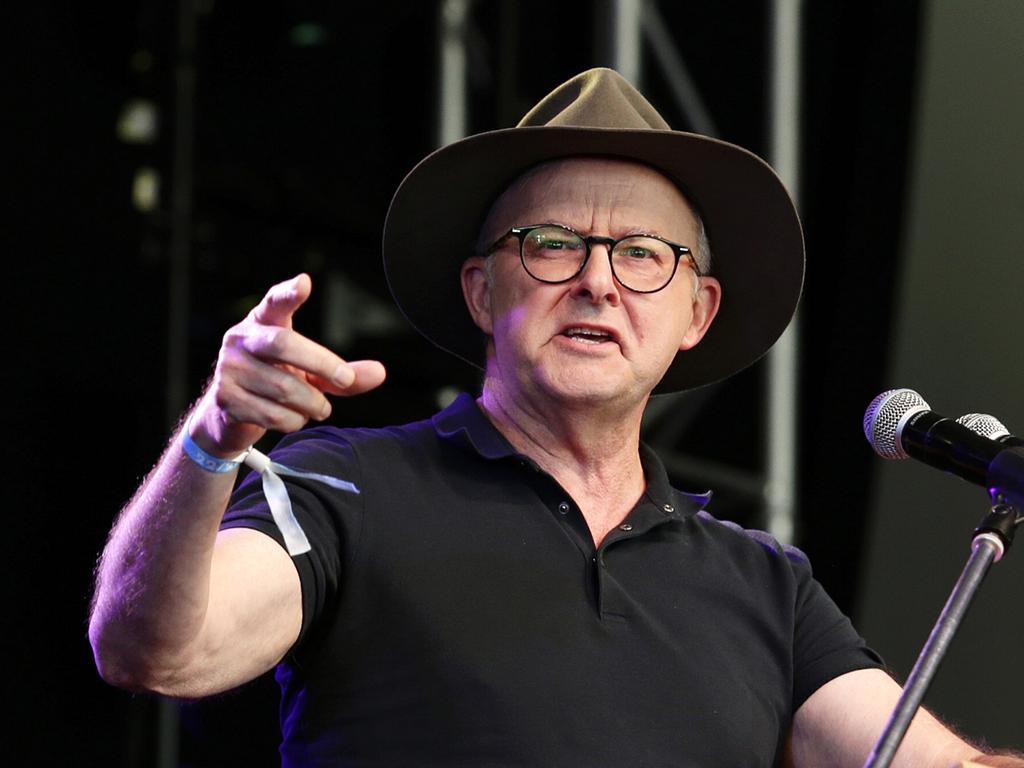

Merritt, The Australian’s former legal affairs editor, has “fundamentally misunderstood” what is being proposed, says Leibler. Indeed, Leibler attempts to rebut Merritt’s view that this voice will deliver anti-democratic outcomes by noting “the only thing Australians will be asked to approve or reject … is the establishment of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice”. Well, not quite, because we are being asked to approve a constitutionalised voice, not one created solely by legislation. And that “entrenched into our Constitution” reality is what opponents like me say will lead to all sorts of bad (unintended for some, intended for some others) consequences, including future judicial activism and anti-democratic outcomes.

Leibler paints columnist Albrechtsen with the same brush. I’ll lay my cards on the table here and say that as one of the very few constitutional law professors in this country who is politically conservative, I saw absolutely nothing in Albrechtsen’s article that dealt in misinforming or disinforming people.

Readers might or might not be happy to roll the dice on what future top judges would do should this amendment pass. But in my view, there is no doubt whatsoever that this will significantly add to the tools our unelected judges have for gainsaying and second-guessing the elected parliament. Indeed, another former High Court justice, Ken Hayne, a supporter of the amendment, has written in these pages making it clear that it is wrong to claim the voice would be non-justiciable.

That has been the figleaf proponents were hiding behind for quite a while. Leibler now offers a new defence: it is a legalistic form-over-substance one, namely that in strictly legal terms the last word will remain with parliament.

In other words, the Leibler claim is that although the Albanese amendment confers on the voice a right to make representations, this is not a constitutional right to be consulted. This is a highly debatable claim and given the sort of recent decisions we have seen out of our High Court it is in my view likely to prove false when cases are brought to our top judges. My bet is that within a few years these judges will lay down that a constitutionalised voice carries with it a duty on government to give advance notice to the voice of relevant legislative proposals along with sufficient time, information and resources to consider the proposal, and then a requirement to consult with it in good faith before adopting the proposal.

Or does Leibler believe our current crop of judges (or worse, given the state of our law schools, future ones) will say the commonwealth can keep the voice in the dark about relevant legislative proposals and once enacted these cannot be challenged, let alone invalidated? My take: it is massively unlikely our top courts will treat this voice body as merely symbolic, meaning Merritt and Albrechtsen’s substantive objections are correct. And it gets worse, because voters will be voting for actual outcomes on the ground, not theoretical constitutional possibilities.

Even if Leibler were correct and I and his three targets were wrong as to what the judges would do, in substance and in terms of on-the-ground realities I think it is almost certain this voice body would become, in practice, a third chamber.

I’ve said it before but I’ll say it here too. In Canada before the 1982 proposed constitutional amendments proponents of an entrenched bill of rights were struggling to get their proposal through. So they put in a s.33 provision that gave the last word to Canada’s parliament to override the unelected judges and then trumpeted this s.33 provision up and down as proof parliament would keep the last word.

Alas, and as some predicted, the minute the Constitution was changed, many of the same people who had pointed to s.33 as a protector of parliamentary sovereignty immediately began insisting it could never be used. It would be illegitimate to do so. In 40 years want to know how many times Canada’s elected parliament has invoked s.33 to claim the last word? Not once. Never.

Canada’s judges have become virtually the world’s most activist. And my bet is that something analogous would happen here in Australia. In practice parliament would never stand up to a constitutionalised voice. When Chris Kenny and others point out that that would be parliament’s fault, the rejoinder is neither here nor there for voters deciding whether to give the voice a tick or not. If you know, going in, that future parliaments will be pusillanimous – because left-of-centre parties want to defer to the voice and because right-of-centre parties lack anything remotely resembling a spine – then why would you, as a voter who is not an MP, sign off on that likely future reality?

Blame and fault are not on the ballot. Outcomes are.

That brings me to Leibler’s remarks about Callinan’s views. He notes that Callinan suspects there will be “a decade or more of constitutional and administrative law litigation” (I concur) and that Callinan believes the “courts might give the voice a larger role than the Constitution would give it” (there’s no “might” about it, for me). Then Leibler makes this astounding criticism: he says Callinan’s “thesis seemed to be that Australians should be afraid of what the courts would do – a remarkable proposition for any lawyer to advance”.

Why is that remarkable? Is every qualified lawyer expected to fall in line with what the preponderance of lawyers or legal academics or judges think? I’d love to hear Leibler have to cash out this line of argument in detail.

No room for iconoclasts or dissenting lawyers or judges? My guess is that 50 years ago, when the lawyerly caste was noticeably to the political right of the median voter, Leibler would not have argued that being against what the courts happen to lay down is somehow illegitimate.

Let’s be clear. No serious legal philosopher believes that the rule of law equates to rule by judges. But today, a half-century on, the lawyerly caste in general terms is massively to the political left of the median voter. In the US, political donations are public information and we know the incredible lack of viewpoint diversity on campuses and among lawyers.

It is patently the same here in Australia. Is that left-leaning reality what tempts Leibler to suggest (and again the suggestion astounds me) that no lawyer can ever criticise or fear or worry about what the top courts will do? I can’t help wondering if it just boils down to the courts here and now being likely to deliver outcomes more in keeping with the druthers of the pro-voice brigade.

Now I can turn more briefly to respond to the December 23 article by Professor George Williams. Williams is a long-time proponent of a federal bill of rights (we used to debate the issue around the country because I am not) as well as having twice tried for Labor preselection. Williams attributes Australia’s low rate of successful s.128 constitutional referendums (only eight successful in 44 attempts) to the No camps’ using “horror hypotheticals” and to their “scaring voters”. I put it down to the proposed amendments being overwhelmingly bad ones. Of those 44 I would have disagreed with the voters’ decisions only twice in the past 120 years.

My guess is that Williams wanted a lot more to be successful, including the two attempts for a bill of rights. But the gist of his piece is that this supposed reliance on scaring voters “works because few Australians possess sufficient knowledge of the Constitution to distil fact from fiction”.

In other words, he and the other members of what is deemed the “independent constitutional expert group” know what they’re talking about. And by implication opponents – people such as Merritt, Albrechtsen, senator Jacinta Price, me and Callinan among many others – do not.

Well, as I said, this is just an argument from authority, a variant of the ad hominem fallacy, one that effectively says “we are smart and well-informed and you are not; so trust us”.

My guess is that well over 90 per cent of the legal fraternity would support a bill of rights, though most voters would not. They’d make similar contestable arguments about its enervated future powers. Any supposed “independent expert group” would come out with this same sort of “don’t worry, it’ll be fine” report. That’s because they’d be drawn from the ranks of those in favour of the proposal. Point us to someone – anyone – who is against this voice proposal who says we don’t need to worry about what the voice will do in terms of increasing judicial activism or undermining democracy.

I finish by reminding all readers of what our current High Court did in the 2020 Love decision, where the majority judges simply read in an effective race-based constitutional right of exemption from deportation for non-citizen Aborigines based on such things as “otherness” (I kid you not). I’ve argued at length that it was the worst-reasoned constitutional decision in maybe 100 years in any anglosphere jurisdiction.

But the point here is that if the judges can do that with basically zero textual warrant or appeals to authors’ intentions, then what will they be able to do once the voice is in our Constitution?

Throw the dice if you want, readers. But be clear that that is precisely what you’ll be doing, whatever reassurances Leibler and Williams try to offer up.

James Allan is Garrick professor of law at the University of Queensland.

In the past few weeks there have been two quite remarkable articles in the pages of this newspaper, both arguing in favour of the federal government’s desire to amend our Constitution to establish an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice.