Expert stress tests show the voice is not a threat

The government recognised this in establishing an independent constitutional expert group to examine the draft wording announced at the Garma Festival by Anthony Albanese. His proposal does three things. First, it establishes an “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice”. Second, it permits that body to “make representations to parliament and the executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”.

Third, parliament can “make laws with respect to the composition, functions, powers and procedures” of the voice.

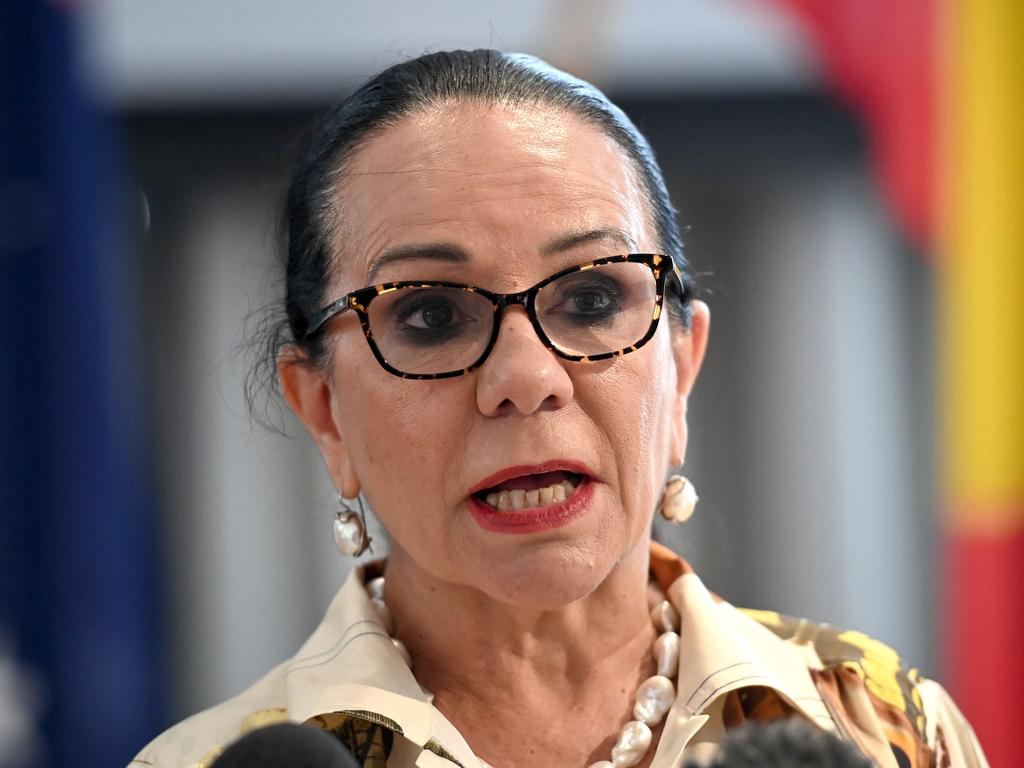

The constitutional expert group comprises people with decades of experience in constitutional law and the work of the High Court, namely Greg Craven, Megan Davis, former High Court justice Kenneth Hayne, Noel Pearson, Cheryl Saunders, Anne Twomey, Asmi Wood and me.

We were asked to pick apart each clause, and even individual words, to determine if the amendment was safe and sound. The aim was to look for problems and unintended consequences in light of the High Court’s approach to the Constitution and how it might interpret these words.

After meetings and considered discussion, the group unanimously concluded the draft amendment provided by the Albanese government was “constitutionally sound in providing a strong basis on which to conduct further consultation”. It reached this conclusion after stress-testing the wording and considering a range of hypotheticals and scenarios. It also examined whether new wording should be added or amendments made to future proof the change.

One important question was whether the draft would grant the voice a veto power over parliament or government. It is clear this is not the case. The wording permits the voice only to “make representations” to parliament and the executive. The word “representations” was carefully chosen to limit the body to an advisory role. There is no basis on which making representations can amount to having a veto.

Nor would the wording of the change amount to a de facto veto due to an implied requirement for the voice to be consulted before new laws are made. There is no requirement that the voice be listened to before a decision being made. Decisions can be made without the voice having its say, and indeed the voice could be ignored if parliament and the executive decide to do so.

The answer would be different if the wording said the voice must be consulted, but it does not do so. To suggest otherwise is to read words into the amendment that are not there.

All this is in keeping with the aim of creating an advisory (and not a decision-making) body, and certainly nothing akin to a new chamber of parliament.

This is consistent with the work of the many other bodies that already inform decision-making by parliament and government. No one could reasonably suggest these other bodies have any form of veto.

The group also considered whether the voice would confer Aboriginal and Torres Islander peoples with special rights. The drafting would not do so. The extent of the constitutional change is only to create an advisory body called the voice that can choose to make representations to the political arms of government. No section of the community is given special rights. At best, the drafting permits Indigenous peoples a new opportunity to provide advice on laws and policies that affect them.

The constitutional expert group recognised that there were a range of ways the Constitution could be changed to bring about the voice. It found that the government’s draft was a reasonable method of doing so in keeping with our constitutional traditions. It is a safe, rather than radical or worrying, proposal that does no more than establish a new point of advice for parliament and government. It is a simple and clear amendment well suited to achieving its goal.

The Prime Minister’s draft does not set out the full detail of the voice. The goal is only to establish a framework and the guardrails within which the voice must operate. The draft does this by making clear that the day-to-day work of the voice, such as how its members will be chosen and its procedures, will be set by parliament. This is consistent with how our Constitution functions.

Australia’s Constitution is not a lengthy rule book setting out every aspect of how an institution such as parliament or the courts work. Instead, it establishes these bodies at a high level and leaves parliament to flesh out the details.

Experience shows this is the best approach due to the difficulty of changing the Constitution and the need for institutions to adapt to the times. In following this path, the amendment preserves the sovereignty of parliament to shape the operation of the voice. Parliament no doubt will take up this opportunity immediately if the referendum succeeds.

George Williams is a deputy vice-chancellor and professor of law at the University of NSW.

Every referendum throws up a host of horror hypotheticals. This comes from the long-established playbook of those who successfully oppose change. A series of unlikely scenarios that scare voters and make them think twice can generate a strong No vote. The fact these are often implausible or fanciful makes little difference. The tactic works because few Australians possess sufficient knowledge of the Constitution to distil fact from fiction.