Labor’s problem is known. The generational-long realignment in voting patterns in Australia has worked, so far, against federal Labor. This was apparent in the Weatherill-Emerson report into Labor’s 2019 election loss — the ALP sits on a deepening fracture between two ideological camps often hostile towards each other.

The report says at the 2019 election the average swing towards Labor in the 20 seats with the highest portion of university graduates was 3.78 per cent while the average swing against Labor in the 20 seats with the lowest portion of university graduates and poor incomes was 4.22 per cent. Labor failed to win sufficient votes in the former to offset its losses in the latter.

It is a devastating signpost to Labor’s identity dilemma. The NSW Upper Hunter by-election merely confirms a voter realignment under way for many years. It is serious but nothing new.

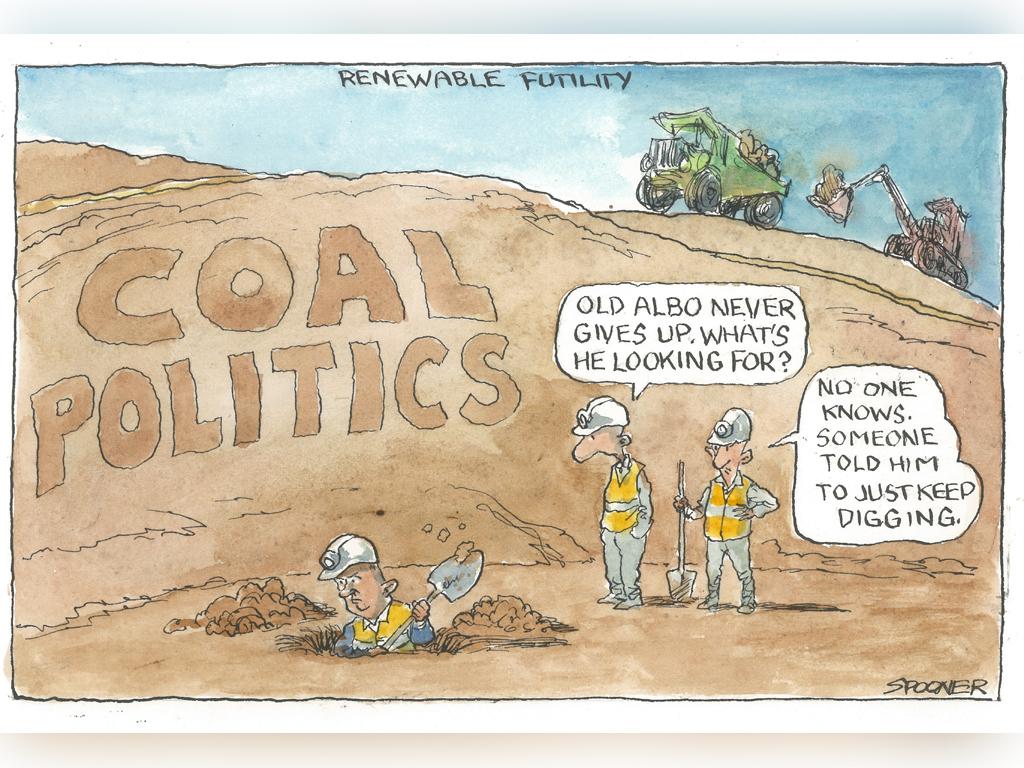

Labor’s dual identities are well known – it is the party of educated progressives, public sector and service delivery employees, minorities and cultural adherents of woke or grievance politics on one hand and, on the other hand, Labor loyalists holding jobs in coal, resources, electricity, gas, water, manufacturing, agriculture and industry, many being cultural conservatives.

This is a vast gulf, likely only to intensify. The division, moreover, is not just about interests. It goes to core values – evident in policy on climate change, fossil fuels, tax, identity politics and treatment of minorities.

The 2019 report from former Labor premier of South Australia Jay Weatherill and former federal minister Craig Emerson argued Labor had no future but to remain as a party seeking to reconcile these dual identities. That is understandable. But the report provided no solution as to how Labor could bridge this divide and there is no sign the current Labor frontbench has any answer.

The government’s decision to construct a gas-fired plant in the Hunter Valley, dubious in economic terms, has delivered a political dividend in spades with Labor openly split on the plan, more evidence of the basic fracture.

The voter realignment also poses risks for the Liberals, notably in prosperous, leafy city seats as post-material and rising environmental imperatives threaten Liberal MPs, the main threat coming from the rising generation of independents that Malcolm Turnbull now seems ready to back.

Scott Morrison and Anthony Albanese operate in a 21st-century politics where Australian society is more divided, political parties are more divided and leaders must construct voting coalitions that span divergent constituencies from the regions of north Queensland to the progressive suburbs of Melbourne.

The Prime Minister won the 2019 election because he met this challenge with less damage to his own side than Bill Shorten was able to achieve.

This is still the situation despite the constant risk from right-wing populism. As Morrison manages his government’s transition to net-zero emissions in 2050 the strains will deepen on the Coalition side – but the evidence, since 2018, is that internal ideological differences are a greater problem for Labor than for the conservatives.

At its heart progressivism thrives in single-issue campaigns. But the movement’s welcome colonisation of Labor is a danger because progressivism, in essence, seeks a new moral order by weakening traditions, institutions and established cultural norms. It tells people they must change and live by new standards and morals, a process that guarantees a backlash.

Labor, therefore, will struggle with its duality. It functions as a banner-carrier for the tertiary-educated, high-income, self-righteous cosmopolitan progressives focused on climate change, social justice and identity politics while it must keep faith with working people or “quiet Laborites” struggling with jobs, dislocation, technological change, stagnant wages and family pressures – people often hostile to the cultural changes under way in relation to gender, sex, religion and the education of children.

This dilemma goes to Labor’s contemporary results. Labor has won majority government only once in the last nine elections. Its primary vote is in structural decline, having fallen from 43.38 per cent in 2007, when Kevin Rudd won, to 34.73 per cent at its 2016 defeat and 33.69 per cent at the 2019 poll when Bill Shorten lost.

Economic aspiration and cultural progressivism are the permanent forces reshaping politics.

But economic aspiration weakens Labor’s class-based economic appeal while cultural progressivism, with its anchor in minority identity and victimisation, undermines community unity.

The Opposition Leader has moved Labor back to the political centre and ditched Shorten’s “tax and spend” agenda. But evidence is scant that Labor’s brand has improved. Albanese offers incremental change when transformational change is probably needed. The truth, however, is that Labor seems beyond the point of significant internal reform.

Meanwhile, progressives keep hailing false dawns — Morrison was supposed to be finished by the bushfires early last year and then by the “justice for women” eruption early this year. Morrison, however, remains not just alive politically but is formulating a strategy that will give him a serious re-election prospect.

The economy and health, not the climate and women, will constitute the next election frontline. Like John Howard, Morrison will target the Labor base vote – his policy message is robust economic recovery, more jobs and lower tax than Labor. His tactic is to drive a wedge through Labor’s competing identities.

As Morrison signalled to this newspaper on Monday, he believes the values of working-class voters are now better aligned with the Coalition than Labor. This is a pandemic-driven update on his 2019 strategy. The pandemic has brought a sense of heightened risk to public attitudes. Morrison and Josh Frydenberg define themselves as agents of security, as protectors against risk, as managers of jobs, health and tax security.

Pivotal to Morrison’s approach are values. Many progressives are still clueless that Morrison won in 2019 not just on the economy but on values. Indeed, the Morrison-Shorten election was one of the most intense ideological battles Australia has seen between conservative and progressive values. Morrison wants to stage a repeat.

The cultural contest on the economy is between aspiration and entitlement, between incentive and redistribution. Despite his big-spending budget that ate Labor’s lunch, Morrison will affirm the Liberal brand: that people want to be empowered, “in charge of their own lives” and not “held back” – an obvious values assault if Labor gives Morrison an opportunity and runs a higher tax policy.

In his 2019 launch Morrison, on stage with his wife, Jenny, invoked family and community virtue in describing the lives of many Australians: “Get an education, get a job, start a business, take responsibility for yourself, work hard.” His bet is that Australian conservatism still runs deep while Labor is a progressive party betting that Australia, sometime, is heading towards a progressive majority.

One bad by-election does not negate a parliamentary term but it does prompt the pivotal question: is federal Labor confronting its documented 25-year-old branding problem or merely drifting in a sea of uncertainty?