‘Sabotage’ claim unfair: united voice could not be clearer

Leibler wrote in his article: “No doubt Langton and Calma have been influenced by the concerns of people including newly elected parliamentarians Kerrynne Liddle and Jacinta Price, both of whom have told The Australian that they are concerned the focus on the voice will distract the government from more urgent challenges on the ground.”

It is absolutely not the case that I have been influenced by Liddle and Price. Neither Liddle nor Price attended our consultative meetings. Nor have they ever spoken to me about the voice. I am influenced by the thousands of Indigenous people who did speak to me and who want to influence policies because they desperately need better living conditions in their communities and a better future for their children.

I haven’t spoken to Liddle or Price in many years, and the last time I spoke to Tony Abbott, who has demanded “all the detail” behind the voice, was when he and Bill Shorten met with us as a group of Aboriginal leaders wanting constitutional recognition after our Expert Panel report, Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution, was presented to Julia Gillard in 2012. Abbott inherited the report and told us he would never act on it.

Leibler is wrong to say I am “motivated by a desire to sabotage the process”. To the contrary, I support a referendum with a simple question: Yes or no to a voice? I also support the democratic notion that voters have a right to be accurately informed about what they are voting for, or perhaps against. This seems to me essential given the extent of the lying and obfuscation from the usual parties. For instance, it seems many Coalition members and former members, such as former PM Malcolm Turnbull, continue to peddle the lie about a “third chamber of parliament” despite the opinions of Queen’s Counsel and constitutional lawyers that this is not the case. Abbott’s claim that there is no detail comes despite our Final Report setting out all the details in 272 pages, and the reports of up to 10 other inquiries and committees, some of which deliberated during his tenure as PM.

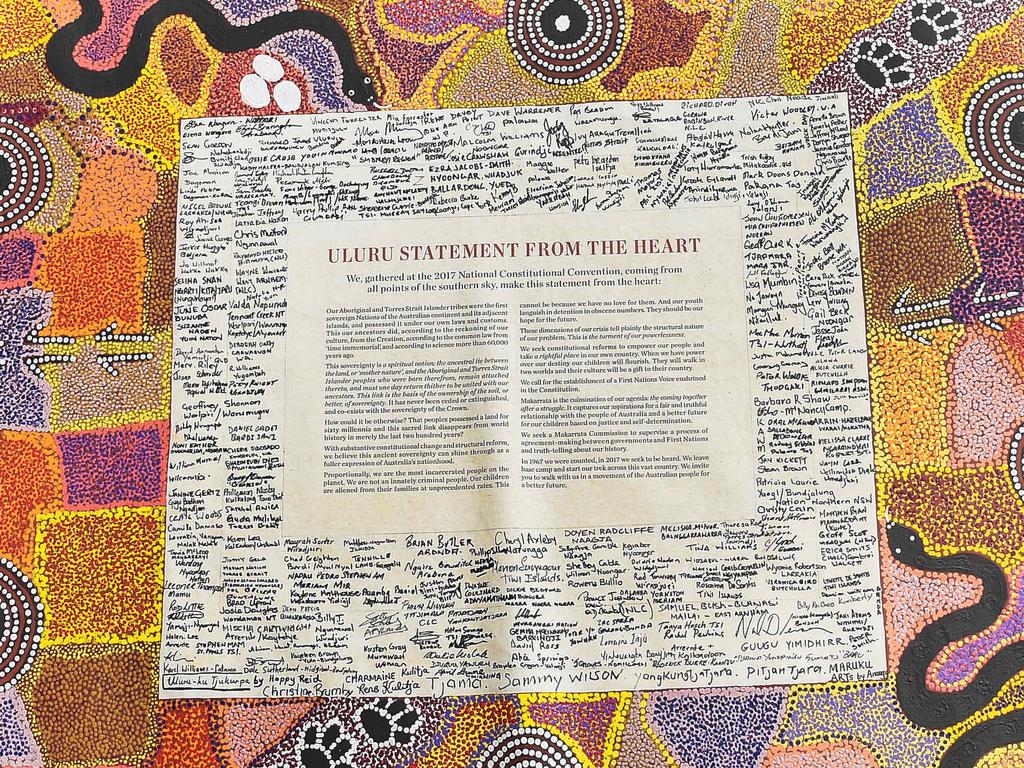

Our voice co-design terms of reference were those recommended by the 2018 Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, chaired by Senator Patrick Dodson (now Special Envoy for Reconciliation and the Implementation of the Uluru Statement from the Heart) and Julian Leeser MP (and now shadow attorney-general and shadow minister for Indigenous Australians).

Leibler well knows that the previous minister, Ken Wyatt, gave us no mandate to consider any of the constitutional matters related to the proposal for the voice, and he specifically excluded from our terms of reference the proposal for a referendum for the constitutional enshrinement of the voice. He well knows that our terms of reference were shaped by the 2018 Joint Select Committee, which recommended there be two separate processes. It recommended that “following a process of co-design, the Australian government consider, in a deliberate and timely manner, legislative, executive and constitutional options to establish the voice”.

Our voice co-design process and terms of reference were in the committee’s first recommendation and it clearly intended that our process should be completed before the legislative, executive and constitutional options be considered by government. It recommended: “In order to achieve a design for the voice that best suits the needs and aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the committee recommends that the Australian government initiate a process of co-design with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.”

The co-design process should:

“Consider national, regional and local elements of the voice and how they interconnect;

“Be conducted by a group comprising a majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and officials or appointees of the Australian government;

“Be conducted on a full-time basis and engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations across Australia, including remote, regional and urban communities;

“Outline and discuss possible options for the local, regional, and national elements of the voice, including the structure, membership, functions and operation of the voice, but with a principal focus on the local bodies and regional bodies and their design and implementation;

“Consider the principles, models and design questions identified by this committee as a starting point for consultation documents, and;

“Report to the government within the term of the 46th parliament with sufficient time to give the voice legal form.”

I feel obliged to those thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who spoke to our team on the voice co-design process who urgently want a model such as is set out in our Final Report. It’s a very simple model and it has overwhelming support among Indigenous people. I also feel for the 52 members of our co-design process, who worked so hard on the design.

In October 2020, Calma and I presented the Indigenous Voice Co-design Process Interim Report to the Australian government. Following its release in early 2021, thousands of Australians from across the country responded in writing and at meetings. More than 9400 people and organisations participated in a consultation process led by co-design members. This was, as we observed in our Final Report, “one of the most significant engagements with the Australian community on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs in recent history”. Over four months, we had conversations with people and organisations across urban, regional and remote Australia. We engaged with people through 115 community consultation sessions in 67 diverse communities and more than 120 stakeholder meetings around the country. We received more than 4000 submissions and survey responses from both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous individuals, communities and organisations.

There was overwhelming support for an Indigenous voice at the local, regional and national levels. Our proposals set out in the Interim Report were not just supported but also improved by the commonsense expressed by community leaders across the country, with the result that our national voice membership model changed to increase the focus on remote people and communities.

We proposed “a strong, resilient and flexible system in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and our communities will be part of genuine shared decision-making with governments at the local and regional level and have our voices heard by the Australian parliament and government in policy and law making”. We have been nothing but clear that a voice to the parliament and government would “complement and amplify existing structures, and would not replace the role for these structures to continue to work with government within their mandates”.

We were very clear in our Final Report that an Indigenous voice would provide the right mechanism for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to be heard on issues that affect us. This will lead to better policy outcomes, strengthen legislation and programs and, importantly, achieve better outcomes for our people. I cannot be accused of wanting any less. To do so is disingenuous and mischievous.

Professor Marcia Langton is associate provost and foundation chair in Australian Indigenous Studies at Melbourne University.

I write to correct the assumptions of Mark Leibler in his article, “Want a voice? It should be a simple Yes or No”, in The Weekend Australian on July 23-24. I served with Professor Tom Calma on the Senior Advisory Group for the voice co-design process from late 2019 to late 2021, appointed by the previous minister for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt.