Philip Lowe is raising the cash rate by 25 basis points to 0.35 per cent because inflation has leapt out of the central bank’s 2 to 3 per cent target band.

“Inflation has picked up significantly and by more than expected,” the RBA governor said, an about-face worthy of those who do see the world through a political lens.

Tolstoy wrote the two most powerful warriors are patience and time. Monetary general Lowe ran out of both, forced to move because of falling unemployment and rising inflation.

The central bank now sees underlying inflation hitting 4.75 per cent this year, a “radical revision”, one observer noted, on its 2.75 per cent call in February.

Inflation was unleashed by global turmoil, local supply snags and, finally, a wages revival. Lowe vows to do whatever it takes to get the beast back in its cage.

The RBA chief said unemployment at 4 per cent was a reflection of the underlying strength in the economy and “it’s good news” we no longer need these “emergency settings”.

The first rise in official interest rates since 2010 may well have been factored into political and household calculations, especially coming off a 0.1 per cent base camp. But that doesn’t mean there won’t be consequences from higher borrowing rates and, as Lowe said emphatically, this is only the first move.

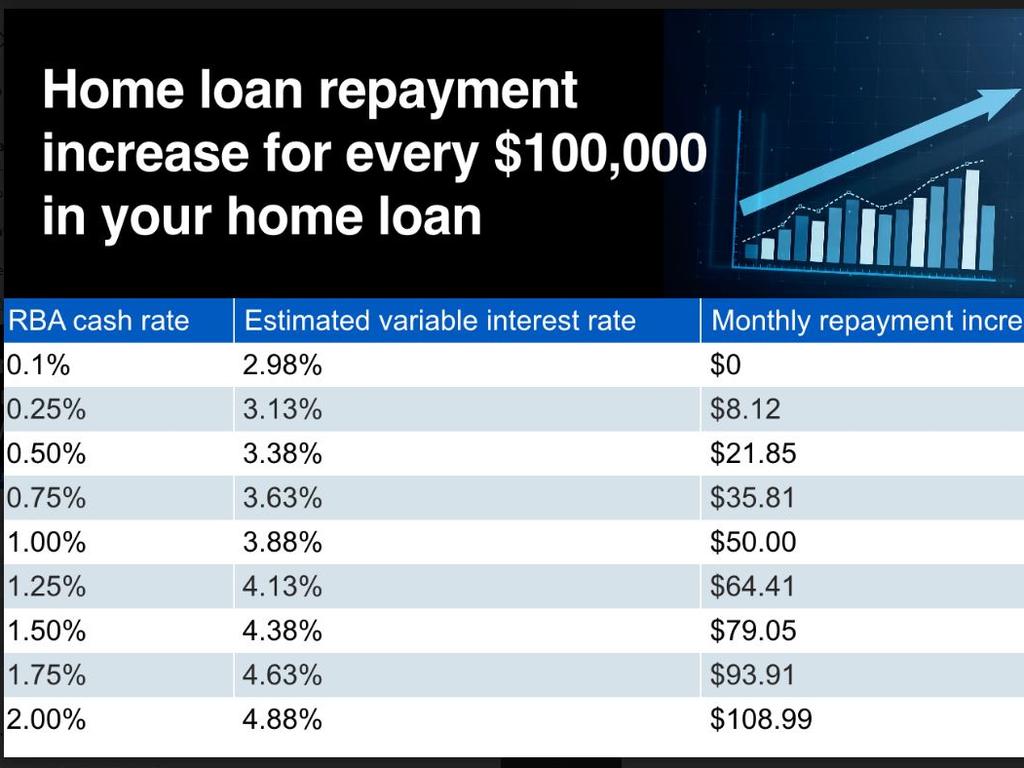

In explaining his strategy to reporters and financial market participants, Lowe said his forecasts factored in a cash rate of around 1.5 to 1.75 per cent by the end of this year, and 2.5 per cent a year later.

Labor’s “triple whammy” of falling real wages, higher inflation and higher mortgages costs is here and Coalition leaders looked rattled after the RBA decision.

Australia’s highly indebted households will have to pull back on spending as they fret about rising mortgage costs. Many borrowers have never been here.

The RBA will be watching closely, through its real-economy lens, as homeowners draw down on substantial cash buffers built up over the pandemic and cut back on luxuries.

Officials will also be monitoring whether there’s been a change to inflationary expectations. After all, for years the RBA tried, and failed, to get a bit of healthy inflation into the system.

There’s no doubt the psychological shock of higher rates on consumers, as hikes come one after the other, will play on the minds of policymakers, as will the stability of the financial system.

The RBA has estimated a rise in its cash rate of 200 basis points could cause a 15 per cent drop in real residential property values over a two-year period. As well, some families will struggle to meet loan repayments if rising inflation is not accompanied by faster household income growth.

Lowe said the bank’s liaison program shows wages growth has been picking up. After years of miserly returns of 2 per cent, companies were now reporting to RBA field agents they were paying wage rises in excess of 3 and 4 per cent.

“In a tight labour market, an increasing number of firms are paying higher wages to attract and retain staff, especially in an environment where the cost of living is rising,” Lowe said.

Economists are divided about how steep the rate rise cycle will be. CBA, Australia’s biggest home lender, now anticipates a 1.6 per cent cash rate by early next year – and staying there – as even small rises will bite into family budgets. ANZ economists believe it will take a cash rate of “3-point-something” to tame inflation.

The surprise March consumer price index result a week ago immediately soured the mood of shoppers, with measured sentiment falling by 6 per cent, just behind the plunge in January when Omicron was at large. Confidence dropped by almost 10 per cent among those with mortgages, more than twice the fall in sentiment among renters or those who already own their home.

But Lowe argues fundamentals are more important than the vibe. Whether someone has a job, is getting pay rises, has a savings buffer or can pay the mortgage matters more than “feelings”.

Getting to normal will take a few years. Lowe said this “would be harder to achieve if the inflation psychology in Australia were to shift materially”, so the decision to raise rates now rather than wait would help.

This rate rise makes things harder for Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg. No question, they too, in the Russian master’s conception, are running out of time and testing voter patience.

During the 2007 campaign the RBA raised its cash rate and John Howard lost – not because of the hike per se, but the central bank’s move punctured the former prime minister’s boastful refrain that “interest rates will always be lower under a Coalition government than under a Labor government”.

The Prime Minister and Treasurer will be sweating on some good news in the wages and labour force figures that will be published on consecutive days in the closing skirmishes of the campaign. So, too, will the RBA, after pulling the rate trigger.

Lowe’s numerous avowals that the crisis has passed, and getting back to “business as usual” is the current strategy, will be seized by the Coalition as a helping hand, as will the RBA’s bullish 3.5 per cent jobless rate forecast this year.

While the monetary general said there was no modern map to guide him on how labour costs and inflation behave when unemployment hits a 50-year low, Lowe declared he would not “deviate” from his march.

Unless something changes: if the war in Ukraine drags on, inflation is more persistent, and the world-beating economy doesn’t hit 4 per cent growth.

Morrison insists the best way to keep mortgage rates low is to soundly manage the nation’s finances. The stimulus was extraordinary, and we need to get to ordinary, sooner rather than later. Whoever prevails in the war must negotiate peace on the economy. The winner must get cracking on the road to fiscal normal, not this drip-drip-drip of more borrowed money by both sides to buy off voter groups.

From now until May 21, there won’t be any talk about fixing the budget. Yet unless repair begins on the taxing and spending fronts early in the next term, the fiscal mountain to scale will seem like an Everest.

The age of free money is over. The Reserve Bank has set off on a climb to monetary normal, a destination whose altitude it does not know, but it’s more likely to be Kosciuszko than Kilimanjaro.