Pell injustice shows why we need to restore fairness to the law

The decision by the primary judge preventing Pell’s legal team from using psychological evidence about the credibility of the complainant points to a much deeper dilemma about how the accused can defend themselves from allegations of sexual assault in 2020.

Pell had the wherewithal and the resources to pursue his wrongful conviction to the country’s highest court. But spare a thought for others in jail today who may have faced what Pell did, and are not so well-equipped to appeal to the High Court. It is likely Pell is the tip of the iceberg.

My colleague, Chris Merritt, deserves praise for exposing this little-known and devastating weakness at the heart of the Pell prosecution. Last September, Merritt revealed for the first time that Pell’s accuser had suffered long periods of psychological problems requiring treatment. But Victoria’s Evidence Act meant that not only were Pell’s lawyers unable to access details of those psychological issues and treatment, but the jury could not be made aware of them, or even the fact Pell’s lawyers asked for them. The public was also in the dark about this until Merritt’s careful reading of Pell’s application for special leave to the High Court.

It is high time that more of us understand how the legal system, not just in Victoria, has become dangerously skewed against defendants in sexual assault cases. It stems from well-intentioned but ill-considered amendments to evidence laws in 2006. In an attempt to ease the undoubted stress and pain caused to complainants of sexual assault from being cross-examined on their past psychological history, section 32D of the Victorian Evidence (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act makes it almost impossible for a defendant to gain access to a complainant’s psychological records or bring evidence of those issues to a jury. The section sets up an impossible circular threshold: without having access to the relevant evidence, defendants must convince a judge that they cannot properly defend themselves without putting the psychological evidence to the jury.

There is, undoubtedly, a need for sensible, measured steps to address the fact sexual assault is under-reported, and the court process is traumatic for its victims. But when these cases are often contests of credibility, it is neither sensible nor measured to strip a defendant of the ability to adduce relevant psychological evidence in that contest.

Pell’s legal team had one hand tied behind its back from the start. This was compounded by the flawed judicial method adopted by Chief Justice Anne Ferguson and Court of Appeal president Chris Maxwell. Without the benefit of seeing and listening to the complainant give evidence at trial, the majority decided that he was a truthful witness, that he was not a liar or a fantasist. The majority’s reliance solely on the complainant’s credibility to uphold the jury’s verdict against Pell delivered a double whammy — it meant Pell faced a reverse onus to prove to the jury that the complainant was lying, but Pell could not satisfy that reverse onus by tendering psychological evidence about the complainant that may have helped to prove that.

The majority’s arrogance was breathtaking because they knew about the complainant’s history of psychological treatment but didn’t mention it in their decision to uphold Pell’s conviction. Indeed, their approach was so simplistic as to be reckless: by relying exclusively on the credibility of the complainant, they effectively discharged themselves from having to carefully consider all of the other evidence that raised reasonable doubts as to whether the alleged sexual assaults could have occurred.

Human nature is fallible. Alleged victims do lie. In the ACT last year, Sarah-Jane Parkinson was sentenced to more than three years’ jail on charges of making a false allegation of rape against her former husband. Studies show that witnesses can also unconsciously lie, genuinely believing something to be true even if it is not. Alleged victims might also be co-opted by others for a cause. Some or all of that may have happened in the Pell case.

Yet ill-considered sections in Victoria’s Evidence Act, that prevent the tendering of psychological evidence, have cemented into law the dangerous tenor of our times. When zealots in the #MeToo movement and Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews say that they believe all victims, they knowingly chip away at a court system that is based on evidence, the presumption of innocence, the burden of proof and due process. Just straight to conviction and jail, then?

Injustice has been legislated into the NSW legal system too. In a recent case, a trial judge was forced, by NSW evidence laws, to exclude a woman’s proven history of making false sexual assault claims. Despite the trial judge pleading for these brutally unfair laws to be reformed, the NSW Berejiklian government has done nothing.

While we wait for the outcome of the defendant’s appeal of the trial judge’s decision, which was heard last week, we are left with the dreadful likelihood that other defendants have been wrongly accused, tried and found guilty where alleged victims have told lies about alleged sexual assaults for revenge or simply because they were suffering from delusions or confusion arising from psychological conditions.

This is what happens when, with the best of intentions, we depart from first principles. In his 1760 Commentaries on the Law in England, the great common law scholar William Blackstone stated the principle that our legal system is founded on: “It is better that 10 guilty persons escape than that one innocent person suffer.”

Some misguided souls might say that Blackstone’s ratio is a get-out-of-jail card for rapists; that it needs to be reversed or restrained to deliver victims justice. In other words, the Blackstone 2020 Victorian edition should read “it is better that an innocent man be punished than a complainant have his or her credibility challenged”.

The #MeToo advocates tell us that men have been getting away with sexual assault for years. That is correct. Some say it is about time the tables were turned. That is wrong. While the desire for revenge is understandable — particularly among those who have suffered greatly — it surely cannot become a new organising principle on which society, and our legal system, is based.

Even for those whose motivating principle is more noble, wanting to bring an end to sexual assault, unbalanced and unfair rules of evidence are not the right way to get there. Substituting one form of injustice for another is not justice, and it is not noble. Once you allow systematic injustice in sexual assault cases, on the ground that Blackstone’s maxim is outdated, where do you stop? Which group of defendants will next be deprived of the means of defending themselves because their alleged crime is under-reported and needs to be reined in?

Who will next be deemed unworthy of basic principles that underpin our legal system? As Pell’s case shows, there, but for the grace of God, go I.

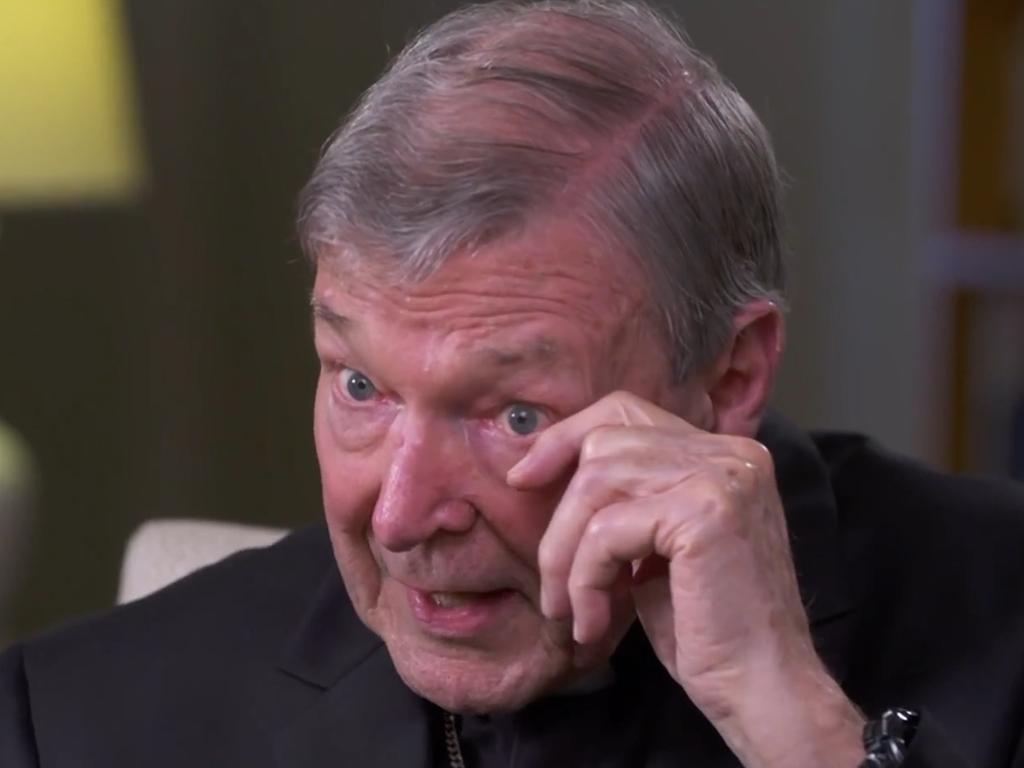

The unanimous decision of the High Court quashing George Pell’s convictions was the end of the matter for Australia’s most famous Catholic priest. But to understand the dreadful state of justice inside our courts, you need to go back to where this courtroom drama started.