George Pell: Diary of an innocent man

‘I had a shower, toilet and firm bed. What else does a man need?’ George Pell reveals the trials of his 405 days of incarceration.

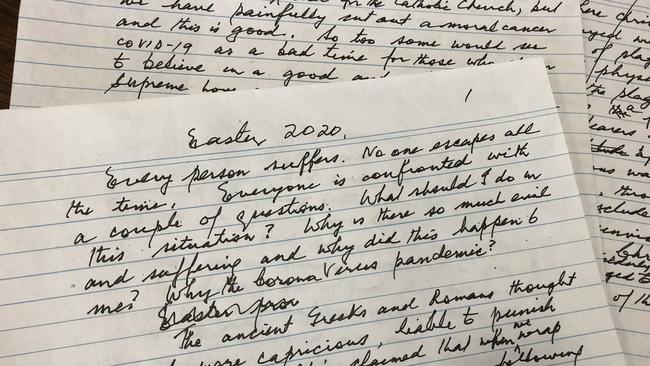

If Cardinal George Pell’s prison journal becomes a bestseller, he can deem his investment in writing pads and pens during the past 13 months worthwhile. Like his prison watch, phone calls, stamps and shaving gear, stationery came out of his $140-a-month budget.

So did the camomile tea and Cadbury Fruit-and-Nut chocolate that became his nightly treat and might remain a habit. Most of his writings, which filled multiple notebooks, were spiritual. But he also wrote about his experiences.

Never one to wear his heart on his sleeve, he puts on a brave face discussing his 405 days as prisoner No 218978.

“It’s not the Hilton but it’s well run,” he says. “I had a shower, a toilet and a bed with a firm base. What else does a man need?” In Pell’s case, books — he was allowed six at a time and he churned through them, as well as magazines and religious journals.

There were “petty humiliations” — think handcuffs when going out, strip searches before every contact visit, twice a month, and attending the Victorian Court of Appeal without his clerical collar. He was denied even a thimbleful of wine to offer mass, but had the chance to attend several masses by a visiting priest or the chaplain at Barwon, Father John McCarthy, 82, who taught Pell in his first year in the seminary in 1960s. Nothing, however, matched the humiliation of signing the sex offenders register in front of a packed courtroom the day he went down — February 27 last year. He wants his name off that register of shame as soon as possible.

Prison officers were courteous and decent, he found. Early on, Pell surprised a group of officers when he greeted them with “good morning, gentlemen” — a description they did not hear often.

In the Melbourne Assessment Prison, prisoner No 218978 was in solitary confinement 23 hours a day. Pell appreciates that was for his own safety, “so I’m not complaining’’. Drawing on his experience as a seminarian in the years before the Second Vatican Council modernised the training of priests stood him in good stead. In those far-off days, seminarians were on “a grand silence” from mid-evening until 9am the following morning. In turn, he has found, jail has been a good training ground for the coronavirus lockdown, which so far has prevented him seeing his family, who visited him regularly in jail. Nor has he seen the two babies named after him, the children of close friends, who were born while he was in jail.

For now, Pell is happy to stay home in Sydney. He will return to Rome, after the pandemic, to see his many friends and pack up his apartment, especially his thousands of books. But Sydney will remain home. He will continue taking a keen interest in the life of the church and will be entitled to vote in any conclave until June next year, when he turns 80. He is ready for a quieter life, “growing a few cabbages … and roses”. But not full time.

He looks back on his four years as Vatican treasurer with satisfaction and still follows developments closely. The reforms he instigated are bearing fruit, slowly. But the Vatican’s structural deficit, already a problem, is worsening as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, which has closed down the Vatican’s main source of revenue, its museums. The Vatican would be tens of millions of euros better off, however, he points out, had the secretariat of state heeded his warnings not to plunge into the London property market at the height of the bubble.

In Barwon jail, near Geelong, Pell was allowed to mix with three other inmates and made friends. One, more technically adroit than he is, retuned his television so he could listen to ABC Classic FM, a sound rarely heard within those walls. He also made friends with inmates who wrote to him, including one who wrote to him most days. He hopes to keep in touch with some. In all, Pell received about 4,000 letters during his time inside — an average of 70 a week. While he lost a lot of weight in jail, he says there was plenty of food, more than he could finish.

“The meals were suitable for men who were 50 or 60 years younger than me who need more. But no sweets, no alcohol.” Pell likes ice cream and missed it. He has enjoyed a scotch and a glass or two of red wine since his release. “I didn’t yearn for alcohol, but I haven’t become a wowser.’’

His deepest regret is the pain his ordeal caused his family and close friends. He was deeply saddened not to be able to visit Sydney priest Father Paul Stenhouse, the former editor of Annals magazine, when he was dying in November, after years of battling cancer. “He was a dear friend and a learned priest. We need more like him.”

Pell is deeply grateful to the donors, large and small, friends and many people he has never met, who funded his trial. Even with their help his superannuation has been wiped out. He is deeply concerned about other innocent people who find themselves in a similar predicament to what he was, without the means to raise the money to battle all the way to the High Court.

Like most prisoners who received visitors, he found his final weeks inside, when visits were stopped because of COVID-19, hard. For the sake of inmates’ and officers’ morale, he hopes “box visits” — where inmates are separated from visitors — are restored as soon as possible. Prisoners close to finishing their sentences, he believes, should be let out early.

As well as writing, reading and exercising, prayer was the mainstay of Pell’s days. He did not take siestas because he feared he would not sleep at night. He slept well, generally, apart from when the “bangers and shouters” along his row of the MAP were in full voice. One night, he listened to an argument between two other inmates, shouting from inside their respective cells, about whether he was innocent or guilty.

Making an effort not to be “my normal pugnacious self”, Pell chooses his words carefully to comment on Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews’s statement after the High Court’s unanimous finding a week ago that the cardinal had been wrongfully imprisoned by Victoria for more than 400 days. Andrews said: “I have a message for every single victim and survivor of child sex abuse: I see you. I hear you. I believe you.”

That view appears to suggest a “presumption of guilt” on the part of anybody accused of child abuse. “Victims should be accepted as credible,” Pell says. “I believe them. But what has to be established is that they are victims. Guilt by accusation is a mark of an uncivilised society.’’ Is Andrews’s Victoria becoming a less civilised society, then? “People can draw their own conclusions.”

A hint of the Pell feistiness surfaces at suggestions he got off on a point of law: “The seven High Court justices read all the evidence and submissions and heard the arguments over two days.” Their judgment, he notes, focused on precisely the points he made to Victorian police when they interviewed him at a hotel near Fiumicino Airport in Rome in October 2016. Those points included Pell’s habit of greeting people on or near St Patrick’s Cathedral steps after Sunday mass. He has been “standing out the front of churches since 1971”, when he returned to Swan Hill as a curate after completing his doctorate in history at Oxford University.

The other points highlighted by the court, which he emphasised to the police, were the established practice of an archbishop, when robed, of always being accompanied in the cathedral and the continuous traffic in and out of the priests’ sacristy after mass.

On that score, Pell now agrees it would have been better if both juries had been taken to St Patrick’s during and after the Sunday solemn mass, rather than on a weekday afternoon when it was deserted. However awkward, being there on a Sunday morning would have afforded jurors a clear picture of what a cathedral is like at its busiest time. “Hindsight is a fine thing,” he says. He admits he had decided to take the stand at the second trial and face cross-examination by the prosecution but changed his mind. His legal team had always advised him not to take the stand.

“And I also thought I might come across as bloody furious because I was bloody furious at how the former sacristan, Max Potter, and Monsignor Charles Portelli, my master of ceremonies in 1996, were treated by the prosecution.”

The guilty verdict at the end of the second trial came as a shocking bolt out of the blue to Pell. “I was expecting to be found innocent or, at worst, another hung jury.”

Pell also wants to point out what he regards as a flaw in Victoria’s 2015 Jury Directions Act, which was cited in the High Court judgment. That Victorian act specifically instructs judges not to suggest to juries that “victims’ evidence … be scrutinised with great care”. He also agrees with the criticisms of Geoffrey Robertson QC, published in The Weekend Australian on Saturday, about the secrecy surrounding the two trials. He admits he readily went along with that secrecy, as did his legal team, when a second trial was in the offing.

“In the long run the secrecy did not help me,” Pell now believes.

Answering the question he posed in his Easter message in The Weekend Australian, “Why me?”, Pell said he was singled out “because he was the most high-profile face of the church in Australia”. He is deeply ashamed about the shocking number of pedophile priests, their heinous conduct and the church’s failure to confront the problem effectively until the mid-1990s. And for all the criticism levelled against it, Pell stands by his Melbourne Response — the first comprehensive Catholic program to tackle clerical sex abuse in the world. It assisted more than 300 victims during his five years as archbishop of Melbourne. And it eventually led to the removal of 30 priests from the ministry. Pell says he is not apprehensive about the forthcoming release of redacted sections of the royal commission report.

Over his 53 years as a priest, Pell has mainly prayed directly to Jesus Christ and to Jesus’s mother, Mary, via the rosary. In jail, he “broadened it out” a bit, appealing to a group of saints to intercede for him because “I thought they would understand”. They included St Mary of the Cross MacKillop, Australia’s first official saint, who was unfairly excommunicated for a time.

The others he appealed to were St John Fisher, the English cardinal beheaded under Henry VIII, Fisher’s friend St Thomas More and Vietnamese cardinal Nguyen Van Thuan, who was imprisoned for 13 years by communist authorities. The last was a friend of Pell. “I don’t deserve to be mentioned in the same group but they all suffered gross miscarriages of justice.”

Pell prayed inside for many people, including his accuser, to whom he bears no ill-will. He also devotes part of his daily office, a collection of prayers and psalms read every day by priests, for the victims of child sexual abuse.