Next time Foreign Minister Penny Wong visits Beijing, she should likewise arrange meetings with people who – like Keating in Australia – critique the ruling party.

First in line might be Qin Gang, who was removed as foreign minister last year for reasons still not disclosed. Thirteen years younger than Wang, he was considered the next-gen guy, smart and articulate.

He is likely to have well-developed views on what’s happening in Beijing and beyond. Then there’s the brilliant law professor, Xu Zhangrun, sacked from Tsinghua University following powerful critiques of the policy direction in which paramount leader Xi Jinping is pushing China.

He is no longer able to post material on China’s internet, and is barred from leaving Beijing. Wong would surely benefit from hearing his take on events. Keating himself provided a precedent of sorts too, by seeking out in Beijing former premier Zhu Rongji, with whom he felt a reformist bond.

This visit, providing an international frisson, might have been especially welcomed by Zhu, since no Communist Party leaders have ever been permitted – meaning trusted – to travel, after retirement, outside their own country at all. However, if Wong is prevented in the future from meeting a critic of the Chinese party-state of her choosing in Beijing, this would cast in hindsight a different, more mischievous shadow on the Wang-Keating catch-up.

We know Keating, of course. As Wong pithily said earlier, he “is entitled to his views – he does not speak for the government nor the country”.

Keating’s views on China were initially helpful, but have changed little over the years, even as the party-state has turned in a dark direction.

In a 2001 speech, Keating said correctly: “In a world of strategic uncertainty, we need a better understanding of what is happening in China…” That includes – maybe should start with – his conversation comrade Wang.

Wang is now in his second spell as Foreign Minister, called back because of the still-secret transgressions of Qin Gang. He is aged 70, the same as Xi. His second chance has been made possible since Xi removed the former age limits in order to ensure his own perpetual hold on power, shunning succession planning.

Wang married handily into a party diplomat blue-chip – or red-chip – family. His wife’s father, Qian Jiadong, was a top foreign affairs aide to Mao Zedong’s loyal premier Zhou Enlai.

His own foreign ministry lists Wang’s roles, in declining order of importance, as a member of the party’s 24-man – no woman appointed by Xi – Politburo, as director of the office of the party’s Central Commission for Foreign Affairs, and lastly as Foreign Minister. This underlines, pointedly, the subsidiary role of the government in contemporary China.

In his first term as Foreign Minister, Wang demonstrated his solidarity with Xi’s combative style and goals by urging diplomats, at a ministry gathering, to display stronger “fighting spirit” in the face of international challenges.

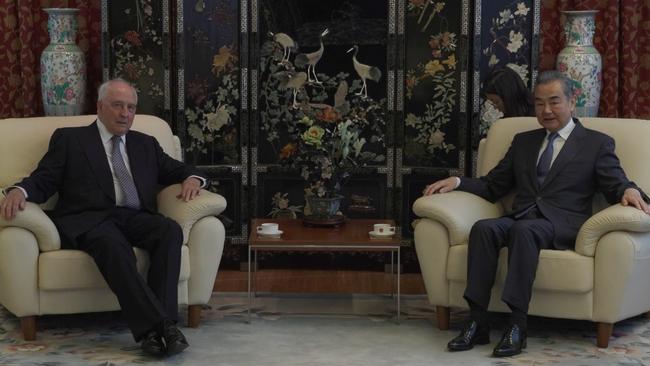

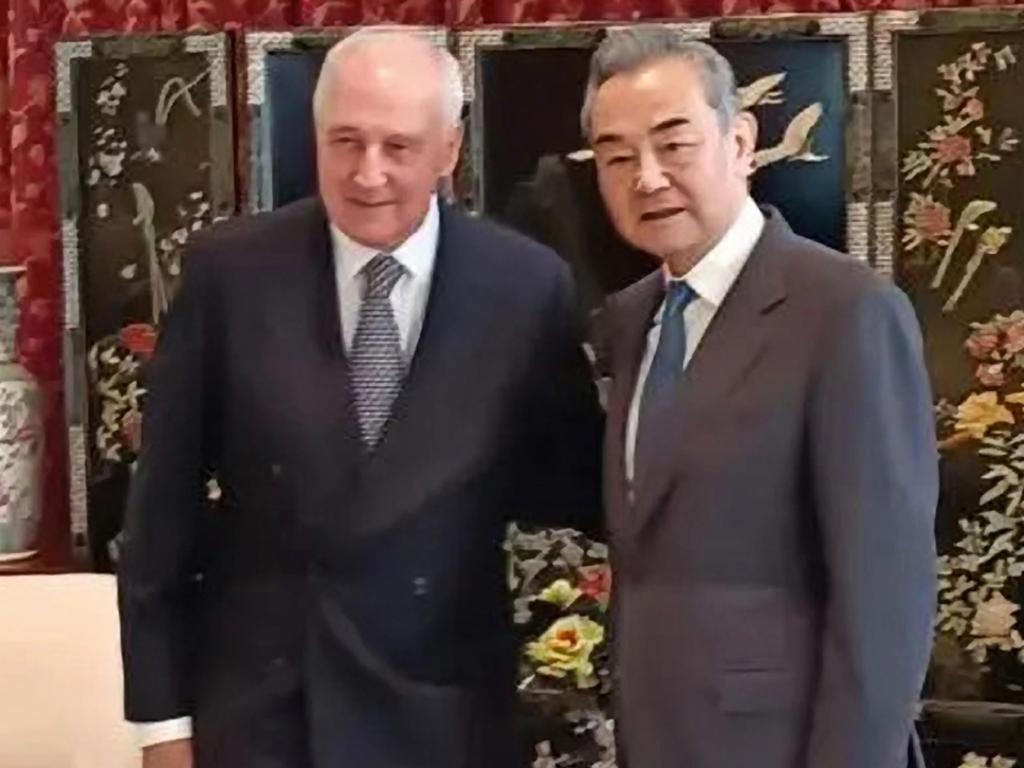

In contrast, Keating said that in their “very pleasant and engaging” Thursday meeting, Wang showed “a keen understanding of Australia’s strengths”.

Excellent. It’s promising if Wang truly views core Australian values – openness, rule-of-law, human rights and democracy – as strengths.

And a splendid way of putting “bilateral difficulties behind us”, as Wang told Keating he wants to do, would be to act reciprocally in granting Wong meetings with party critics in Beijing.

Only, don’t hold your breath.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

We should welcome Thursday’s meeting arranged by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi with former prime minister Paul Keating, which sets a healthy precedent.