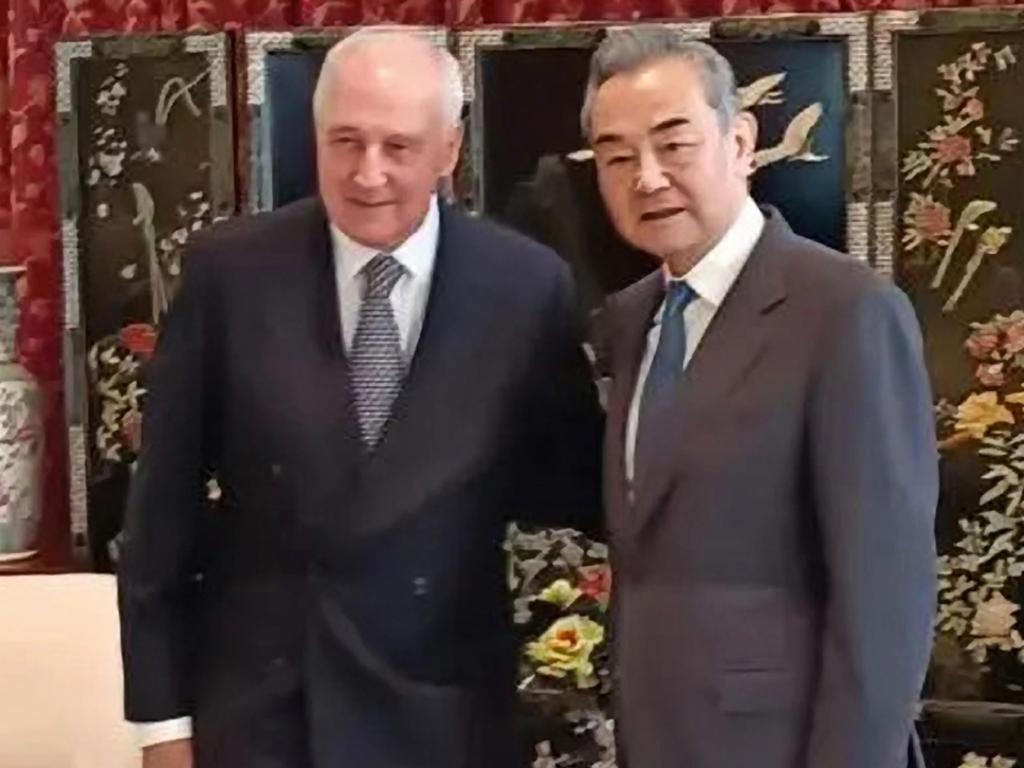

Former Prime Minister Paul Keating and the visiting Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi have both earned the title this week.

Keating has said there was nothing off about his summoning to the Chinese Consulate in Sydney on Thursday. His protests were about as convincing as his claim to being a supporter of the Albanese government’s foreign policy — “most, if not all the time”.

“The Chinese are tickling his ego. Which he loves, of course,” one of Keating’s friends told me.

They were also getting footage for Beijing’s propaganda machine — an important part of China’s statecraft in the Xi era. It’s why Chinese state media were invited into the Consulate to record the meeting, while The Australian’s Noah Yim was kept on the other side of its formidable security fence.

Chinese state media routinely features a certain type of Australian making fools of themselves. The other day, Griffith University’s Colin Mackerras was, once again, in the China Daily, on this occasion telling the masthead that China was neither an autocracy or one-party state. What can you do but laugh?

Keating, however, is a much bigger prize. It is why many of his friends and associates hoped he would have the good sense to decline the Chinese Foreign Minister’s invitation. His ego had other ideas.

Australia’s Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s response to the Keating circus has been pitch-perfect. Her performance at a solo press conference on Wednesday after her meeting with Mr Wang was as impressive as the Chinese Foreign Minister’s decision to avoid it was cowardly.

But, to be fair to China’s foreign minister, he operates in a terrifying political world overseen by Xi Jinping. A press conference in Australia presents endless possible ways to embarrass Beijing and, more problematically for Wang, China’s supreme leader.

If Wang had allowed an Australian or New Zealand journalist to ask even a single question on his five day trans-Tasman trip, he might have been asked what has happened to his predecessor Qin Gang. China’s previous Foreign Minister had been scheduled to visit Australia last year, but was instead “disappeared” into China’s detention network where he, presumably, remains.

“What can he say?” said one person, who has been liaising with Wang’s delegation during the trip.

These are the terms of engagement in Australia’s relationship with China in the second decade of Xi’s reign. When China’s leaders visit, they will bring China’s rules — or they won’t turn up.

The Albanese government has done as well as it could managing that reality. It is in our interest that Canberra keeps talking to Beijing, so long as the Australian government is under no illusions about the limitations China’s political system puts on the relationship.

Wang’s stated desire for “mutual trust” will remain an empty phrase so long as China is this paranoid and controlling.

That has posed challenges for all of the Australians who have agreed to participate in the various Chinese initiatives on this trip.

The Australia China Business Council, for example, banned Australian journalists from their lunch meeting with Wang Yi, while Chinese media were allowed in. It was an incredible double standard for an event held in Canberra, not Beijing.

Worst of all has been the spectacle Keating has allowed China to make of him. Ultimately though, this exercise in Chinese statecraft seems to have backfired.

Its lasting effect will be to undermine trust between the government and Beijing — and to further diminish Potts Point’s most outspoken “low-level red”.

There is a Chinese term for someone who tries to promote the Communist Party, but does it so ineptly they embarrass China. They are called a dijihong, or “low-level red”.