Palace letters: The Whitlam dismissal is still in dispute

In ordinary times, the Australian people vote for their members of parliament, with the person able to command a majority of votes in the House of Representatives entitled to become prime minister. The role of the governor-general is to follow the lead of parliament and otherwise to act on the advice of the prime minister in determining things such as the calling of an election or giving royal assent to legislation.

It is important that the governor-general not exercise an independent discretion. The office holder is not an elected official and derives no authority from the Australian people. To act contrary to parliament or the instructions of the prime minister is to subvert the democratic character of our system of government and risk a constitutional crisis.

There are necessary exceptions to this rule. Rare and extreme cases can arise when the governor-general must act unilaterally. This includes a power to dismiss a prime minister where he or she is defeated in the lower house on a vote of no confidence and refuses to resign. It is also accepted that a prime minister can be sacked where he or she persists in unconstitutional conduct. In these cases, the governor-general is a check on the wrongful exercise of power by the nation’s leader.

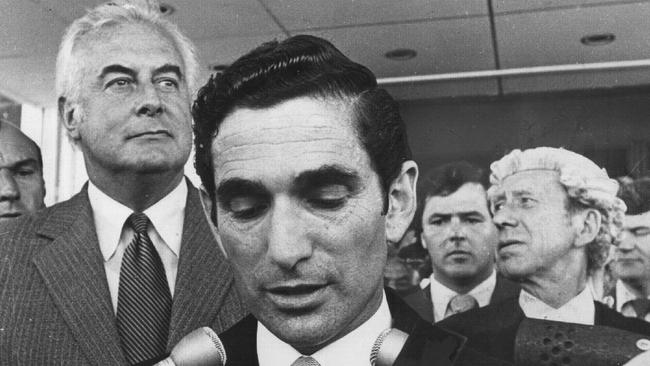

Powers of this kind are called reserve powers. They are to be exercised in an emergency, and only as a last resort. The dismissal of the Whitlam government in 1975 raised questions about the extent of these powers. Whitlam retained the support of the lower house but was unable to secure the passage of his government’s budget bills through the Senate.

At issue was whether the failure to pass the budget bills meant that Whitlam could be sacked by the governor-general. The Constitution says nothing about this, nor about any other reserve power. The answer instead lies in the conventions that surround the office of governor-general. These are derived from the Westminster system of government. However, the British system lacks an upper house that is anything like our Senate. Its House of Lords is unelected and is more limited in its powers.

There is a strong argument that no such reserve power exists. The House of Representatives and not the Senate is the house of government. It also threatens instability to leave the fate of every government in the hands of a Senate that is chosen through proportional representation. It is unlikely a government will command a majority in that chamber, and so there is the risk that non-government members will band together to bring down a prime minister to advance their political agenda.

These arguments cannot be resolved. There is no authoritative document to turn to, nor will the High Court rule on the content of conventions. Instead, the issue is left to conjecture and politics. Inevitably, the answer is coloured by a person’s political leanings.

Coalition members naturally favour the view that Kerr was able to dismiss the Whitlam government, lest the legitimacy of the Fraser government be called into question. Labor members on the other hand decry the actions of Kerr, casting him as the agent of an undemocratic coup.

The letters detailing correspondence between Kerr and Buckingham Palace over these fateful days do not contain a smoking gun. They do not show that the Queen advised or encouraged the dismissal of the Whitlam government. They suggest instead the desire of the palace to distance itself from these events.

The palace recognised the existence of the reserve powers but cautioned against their use except as a last resort. This recognition may have given Kerr comfort, but there is no doubt that the decision was his.

Kerr’s dismissal of the Whitlam government using a reserve power that may or may not exist remains an open wound in Australia’s democracy. Since the Dismissal, parliaments have avoided a like scenario by refusing to block the budget bills, thereby heading off another constitutional crisis. This, though, is only an act of self-restraint. Any future parliament can repeat the events of 1975 and once again throw into relief questions about the role of the governor-general and whether a prime minister can be brought down by the Senate.

It is long past time that Australia fixed this problem. We kid ourselves to think that the events of 1975 could never happen again. The rise of populism around the world shows how readily politicians have been prepared to defy convention and constitutional niceties. We need to avoid any such possibility by changing the Constitution to make it clear that a prime minister cannot be dismissed by the governor-general if the Senate refuses to pass the budget bills.

George Williams is a deputy vice-chancellor and professor of law at the University of NSW.

The release of the Palace Letters has shone light on a flaw in our system of government. This is the possibility that the governor-general can dismiss a prime minister who enjoys the support of the House of Representatives. Sir John Kerr said he exercised such a power to dismiss Gough Whitlam on November 11, 1975. However, it is not clear that such a power even exists.