Our China relationship needs help before it’s too late

There is a dangerous mood afoot in parts of the Canberra bureaucratic and political systems. Beyond that, these dangers now extend into our opinion-making elites. What is the goal of our China policy? If we operate on the assumption that China is the enemy then, as history foretells, China will become the enemy. Nothing is more certain. Our assumptions will be realised and the worse things get, the more the China hawks will boast how right they were.

This process now is being played out. The deteriorating ties with China have a life and momentum of their own. The latest proof was China’s retaliation against Australian journalists last week. Of course, the originating problem is President Xi Jinping’s ruthless, controlling and assertive strategy. We can all agree on that. But the associated risk is Australian fatalism.

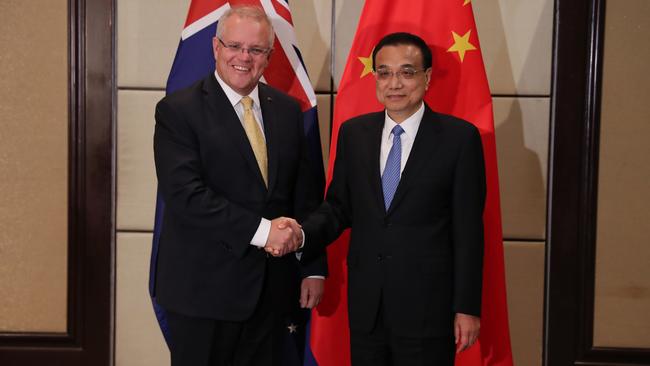

One day, hopefully, Scott Morrison will sit down with China’s Premier, Li Keqiang. What positive messages, what areas of co-operation, what methods to repair relations will he offer? Listening to much of the debate about China in Australia you would think a litany of warnings, dissatisfactions and denunciations of China constitute a policy. Well, they don’t.

What is Australia trying to achieve? It is possible to support most of the Turnbull and Morrison governments’ specific decisions that relate to China — as I do — but still ask this question because it is not sufficiently answered. There is one stance that should be rejected outright: that China has become such a hostile power that Australia must accept whatever retaliation Beijing inflicts in order to honour our sovereignty and values. This is the road to doom, but it has its champions.

There are three myths about China that cloud our minds. The first is that we can do nothing to improve relations because that would only compromise who we are. Such thinking is monumental folly. The China debate cannot end with Australia luxuriating in its resolution when what is needed is judgment.

This country has much to lose if today’s downward spiral continues for another three or four years. A circuit-breaker is needed, neither easy to identify nor implement. But a policy effort to put a floor under the deterioration is essential along with the recognition that even stabilising the present situation will be an immense task.

Yet the domestic debate on China is being driven in only one direction because, unusually, the right and left agree. The right, always threat oriented and alert to sovereignty infringements, sees Beijing as an existential danger. The left, unable to excuse China’s human rights abuses on an industrial scale and its evolving surveillance state, sees Beijing as an irredeemable offender.

During 2016-18 Australia underwent a necessary awakening about China. It was a worldwide phenomenon but also a particular Australian event. This is because more than any other Western nation Australia was the beneficiary of the post-2003 China boom and, as a consequence, became fixated on the need to prove an assertive China could not hold us hostage.

We have now made this point, over and over. Our attitude towards China must transcend a reoccurring cycle of “you cannot intimidate us” based on endless examples of Beijing’s infringements. It would be a mistake to “fix” relations by selling out to Beijing; but it is an equal mistake to offer nothing and make no effort to “fix” relations for fear of looking as if we have sold out.

It is difficult to assess what interest China has in salvaging bilateral relations but Australian policy needs to interrogate this subject.

The second myth is that our massive resources trade is safe from Beijing’s retaliation. Why is this so? China now invests in alternative sources of iron ore. Yet we assume Beijing won’t act against our coal, liquefied natural gas or iron ore because that would hurt China. This answer is too short-term when China thinks long term; witness its 2025 Made in China strategy of self-sufficiency in core technology.

Does anybody doubt China wants to reduce its dependence on Australian imports? Yet the people who keep pointing out that China is an authoritarian, ideologically bound, one-party state are often the same people saying when it comes to the resources trade China will act as an economically rational liberal state, thinking only of price competitiveness. Have no doubt, if the downward spiral continues, Australia has stacks of treasure yet to lose. Resources will come into play.

And if you think relations between Western Australia and the rest of the country are strained now, you cannot imagine the fracture that will enter our federation at that point. China has thrown out the rule book this year; it has engaged in retaliations once merely the subject of university seminars — witness barley, beef, wine and media among others. And Australia doesn’t know what’s coming next.

The third myth is that because the rupture in relations is not primarily Australia’s fault but stems from China’s own actions that we have little or no discretionary capacity in this situation.

This is a mindset problem. The Trump presidency posed many risks for Australia but we expended huge efforts and prime ministerial capital to keep the ship afloat (explained in detail in the Turnbull memoir).

Morrison says he will be “patient and consistent” with Beijing. He won’t hang by the phone for a call. He announces that Australian policy is “independent” and not chained to the US. But these messages cannot compensate for the mounting conflict of national interest between Australia and China on regional, strategic, technology and investment issues. The areas of conflict have expanded and the areas for co-operation have contracted. But they have not disappeared.

In this new normal Australian policy needs to rebalance. We need to give greater priority to where Canberra and Beijing can work together, not just assume we become permanent adversaries. This must start with the renewal of economic, trade and tourism ties in the post-COVID-19 world where substantial mutual interest still exists.

Canberra needs to ensure that the intelligence and security agencies do not dominate bilateral relations. One policy veteran told me: “These agencies have more influence now than during the Cold War.” Certainly they have set the mood. Signs are that Chinese action against the two Australian journalists was driven at least partly by ASIO probes against Chinese journalists in Australia. So, how successful was this transaction?

Our foreign interference laws can set up a cycle of action and reaction. The obvious answer is to say: Beijing should stop its interference. The harder, realistic response is to say that Australia must be careful how it operates in that grey area where there can be a fine line between interference and influence.

In the early 2000s Michael Thawley, our ambassador to the US, organised the Friends of Australia group in the US congress to pressure the American political system to deliver the free-trade agreement with Australia. There would be no hope today for any Friends of China group in the Australian parliament. Any such influence would be seen inevitably as interference.

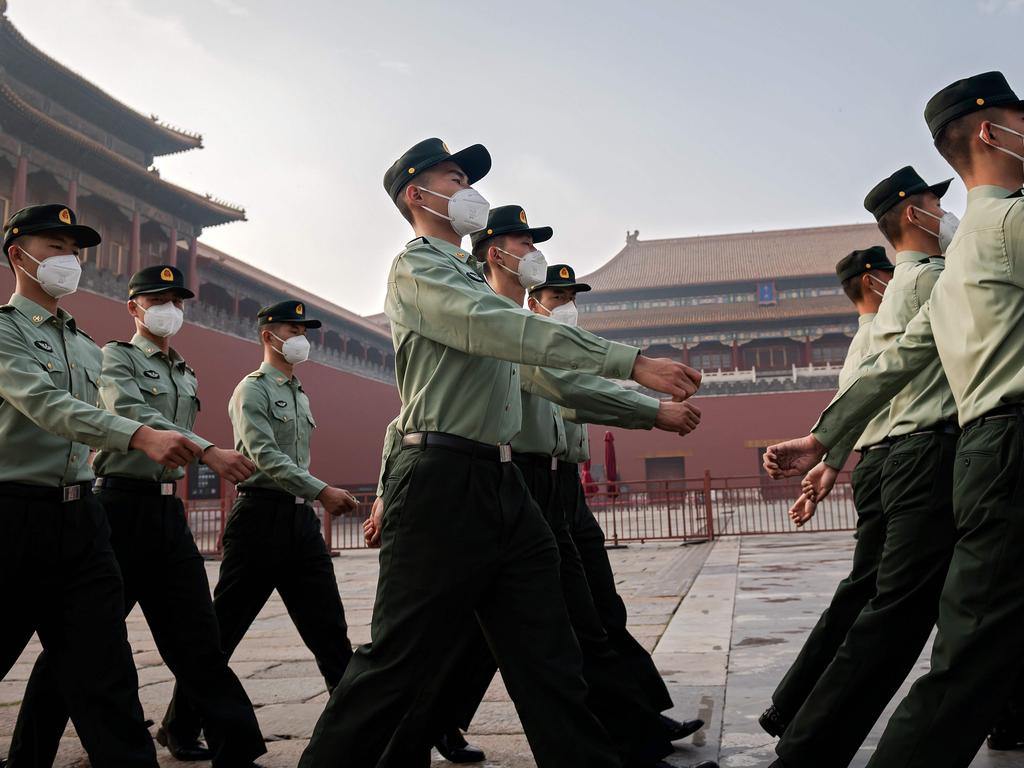

China is entrenched now as the dominant power in our region and its assertive, sinister, authoritarianism won’t disappear soon. We have a choice — to assume the only option is to treat China as an adversary power in a relationship guaranteed to deteriorate further, or to curb the fatalism and put a new priority on trying to halt this vicious spiral.

The task of Australian foreign policy is to see the world as it exists but not fall victim to that reality. Applied to China this demands a brutal recognition of the downward spiral in our relations but a purging of the pessimism that Australia can do nothing to improve things.