China crisis an unavoidable test of Australia’s resolve

The shuddering crisis in Australia/China relations bears one clear message: Beijing will not allow us to continue to grow rich from our relationship with China.

The Chinese government took its hostage diplomacy to a new level when it sent security forces to the homes of ABC correspondent Bill Birtles, in Beijing, and Financial Review correspondent Mike Smith, in Shanghai, to tell them they could not leave China and would face security questioning.

After a tense four-day stand-off, in which they took shelter in Australian diplomatic premises, both were eventually allowed to return to Australia.

This marks a distinct new stage in Beijing’s harassment and mistreatment of innocent foreign nationals. It sends a message to every Australian in China — you are at risk.

It also suggests that the baleful contradiction at the heart of Australia’s national outlook is becoming more acute, more tense.

Until now, we liked to think that we could get rich from China and also protect our national interests. Beijing will likely no longer allow this luxury.

Beijing has taken targeted action against our beef, barley and wine exports, and suggested it could discourage or stop Chinese tourists and students coming to Australia, whenever that kind of travel resumes. According to Beijing’s import statistics, our exports to China declined by 27 per cent in August. In 2019 Australia exported $169bn worth of goods and services to China. Services were a paltry $19bn of that.

For all that Australia has developed domestically as a services economy, it is bulk commodities, our old, old strength, that are our big exports and underwrite much of our prosperity.

In 2019 we exported $79bn of iron ore to China, $16bn in gas and $14bn in coal. Those three commodities together made up $109bn of our exports. They are not the whole story of the Australian economy. But they are a very big part of our prosperity.

However, Beijing has become increasingly aggressive internationally and despotic domestically. It launches constant cyber attacks against Australian institutions and steals huge amounts of our intellectual property. It engages in clandestine influence activities to pervert the course of our politics.

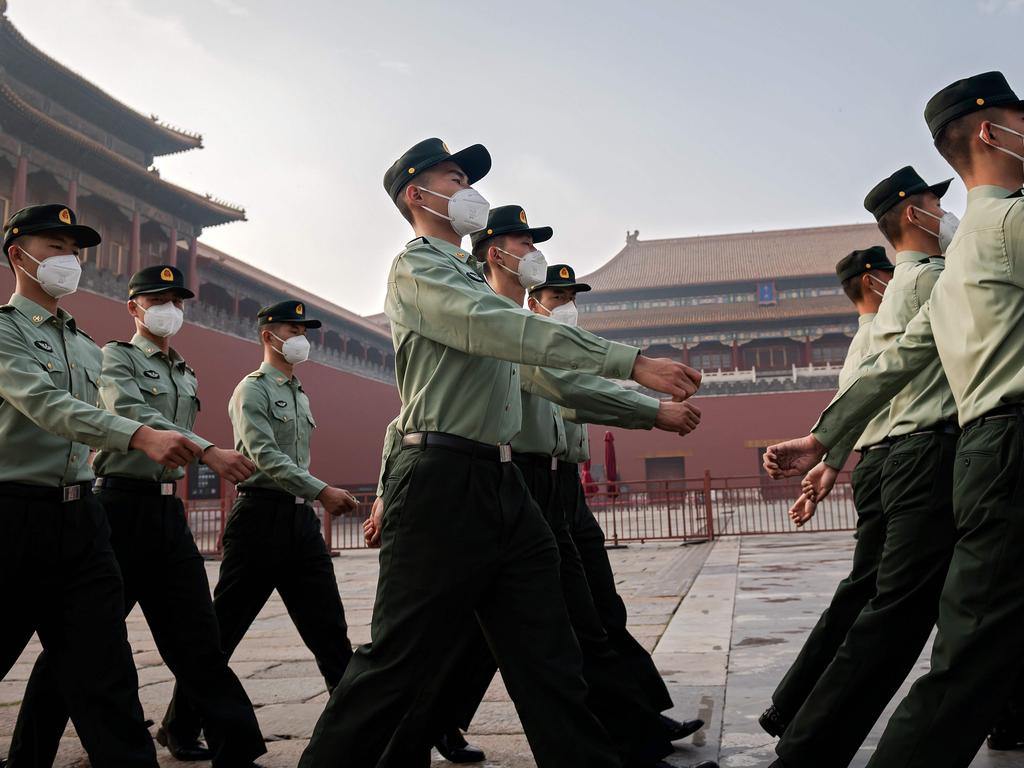

It intimidates and manipulates its student population. It has occupied, constructed and militarised a chain of islands in the South China Sea, which in themselves compromise our strategic security. Our security agency chiefs say espionage directed against Australia is at a greater quantity, and more sophisticated, than ever before, including at the height of the Cold War. Malcolm Turnbull’s memoirs are one of many public sources telling us that the Chinese state is overwhelmingly responsible for this. Beijing has systematically taken Australians in China hostage for use as diplomatic leverage.

Beijing has engaged in debt-trap diplomacy in the Third World, including in the South Pacific, where our agencies assess that it wants to build a military base, which would be disastrous for our security.

Where Australia has taken actions to protect its core national interests — such as keeping its 5G network secure from foreign penetration — Beijing has reacted with punishments for Australia.

Until now those punishments in the trade field have concentrated on areas such as wine, where replacements for Australian products are easily available. Australians have taken a perhaps mistaken sense of security from the idea that our commodities — at the quality, price and reliability we provide — cannot be replaced by Beijing.

Think again. Beijing is involved in developing iron ore mines in Africa and is pioneering a new fleet of super tankers to make it more economic to transport iron ore from Brazil.

Just as nations like Australia, the US, Britain, Canada, Japan and many others are reassessing whether it is sensible to have their supply lines dominated by China, so in Beijing there is a mirror discussion — do they really want to be dependent for the majority of their iron ore on a nation like Australia, which they cannot control and which insists on push-back against Beijing’s influence efforts and strategic assertion?

So is there any way Australia could continue a good, harmonious relationship with China that would leave the bulk of the trade relationship undisturbed?

Yes, there is.

One senior source told Inquirer exactly how we could achieve a lasting, good relationship with Beijing, if that’s what we want. We could: sign up to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, welcome Huawei into the heart of our 5G network and NBN, revoke our foreign interference legislation, abandon our foreign relations legislation (which will subject state government agreements with foreign nations to federal approval), abolish our foreign investment limitations, ratify the extradition treaty so people Beijing accuses of crimes can be sent from Australia to face the Chinese criminal system, allow unfettered research collaboration between our universities and Chinese universities in areas of technology that have military and citizen-control applications, desist from patrolling and surveillance activities in the South China Sea, stop joint military exercises with Asian nations Beijing doesn’t like, such as Japan and India, stop joint military exercises with the US, throw US Marines out of Darwin, close the military communications joint facilities we host with the US, cut our own defence budget, abrogate the US alliance, stop Chinese dissidents, Tibetans and Uighurs from visiting, and get our media to stop saying disobliging things about the Chinese Communist Party.

Nothing guarantees a good relationship with Beijing, as even its most abject client states will attest. But if your overwhelming objective is a good relationship, either for its own sake or to facilitate trade, that’s how you’d do it. The problem of course is that if we did all that we would cease to be a sovereign nation at all, and our security would be entirely dependent on the whim and generosity of the Chinese Communist Party.

Nothing is more foolish, more revealing of a kind of sheer unrelenting strategic stupidity that denies facts and ignores evidence, than to think that by moderating our tone, getting a little more nuance into our statements, speaking with yet more tender regard, we could mollify Beijing while safeguarding our national interests.

What Beijing seriously objects to in Australian behaviour is the serious acts of substance we take to protect our national interests.

On Friday the Chinese Foreign Ministry accused the Australian embassy of interfering in China’s “legal sovereignty” by supporting the two Australian journalists who were under threat. The shrill nationalist Global Times revealed that four Chinese journalists in Australia had been interviewed by ASIO and two Chinese academics had their visas cancelled while they were overseas.

It is worth pausing to note that DFAT performed brilliantly regarding the Australian journalists. DFAT’s early assessment of the threat to the Australian journalists, their urgent warning the journalists should leave, was analytically right. Its actions in sheltering the journalists and negotiating their safe passage out was brilliant, and courageous. Diplomats get some protection but they too can suffer harassment. Sheltering Australians in this way requires some real courage as well as high professional competence.

Parts of the Australian media in response to all this engaged in two acts of analytical absurdity. They declared the Chinese action against the Australian journalists was retaliation for the earlier Australian actions. In fact neither the Australian government nor any intelligence agency believes that. Nobody knows Beijing’s motivations.

Dennis Richardson, the former head of ASIO, cautions Inquirer to look at the episode not only in a bilateral light, but internationally. Beijing this year expelled US correspondents from The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal. And it engaged in continual low-level harassment of some staff at the remaining US news agencies.

This is the greatest contrast to my own experience as a Beijing correspondent in 1985. My only brush with security agencies came when I got lost walking around one night. A mysterious car pulled up beside me and a dapper man offered me a lift back to my hotel.

Beijing’s savage clampdown in Hong Kong also shuts down the world’s most important source of independent China media analysis. Beijing doesn’t want serious Western scrutiny.

Some Australian media also described the Australian and Chinese actions as tit-for-tat retaliations. This is ridiculous. ASIO did not question any Chinese journalist compulsorily.

No one was threatened. No one faced detention. No one breached the privacy of the Chinese journalists involved. Neither ASIO nor any other agency disturbs a foreign journalist for political reasons, only if there is an investigation into clandestine, improper foreign influence, at the direction of a foreign government, or espionage.

The Chinese journalists who left Australia did so, unharassed, of their own free will.

Similarly, the Chinese academics whose Australian visas were cancelled can appeal these decisions. To cancel a visa on security grounds requires a comprehensive report from relevant agencies and a personal decision by the Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton. Such a move is never undertaken lightly.

The object of ASIO is to “reduce the security harm”, not to humiliate or punish the person involved.

The Australian journalists, on the other hand, could easily have ended up in indefinite Chinese detention. The Australian woman, Cheng Lei, who worked as an on-air host for a Chinese state television agency, and who was not a controversial figure, is in such detention now, perhaps only because she is Australian. Two Canadian academics, one of them a former diplomat, have been in Chinese detention for nearly two years as part of Beijing’s gruesome hostage diplomacy.

Nor should Australians flatter ourselves that we are uniquely the subject of Beijing’s enmity. In the past 12 months Beijing has had ferocious disputes with the US, India, Britain, the European Union, Canada, the Czech Republic, Sweden, Vietnam, The Philippines and New Zealand. Take it a year or two back before that and you can add Japan, South Korea and many others. Were the national leaderships of all these countries incompetent, unduly sensitive, missing a vital ingredient of nuance?

Or is it the fact that Beijing’s extremely aggressive and expansive strategic and commercial ambitions, and its fairly lawless pursuit of those ambitions, have caused resistance among all those nations that Beijing then objects to?

One of Australia’s most brilliant Sinologists, Geremie Barme, attributes it to the deep continuity of culture within the Chinese Communist Party itself. Xi Jinping, he says, acts more like a traditional Chinese emperor than any previous communist leader, even Mao Zedong. Barme says: “Xi is a bellicose, struggle-centric person who believes in constant struggle, constant purges, constant uncertainty. He believes stability is maintained only by maintaining this constant tension and uncertainty.”

The world is entering an acutely dangerous period. Many strategic actors have described to Inquirer a variation on a strategic scenario of acute danger. The Chinese economy is slowing. The failures in governance of the Xi period, especially but not only relating to COVID-19, have intensified the feeling of paranoia in Beijing. Nationalism is the prevailing ideology.

Xi has made it clear he wants to subjugate Taiwan during his presidency. If Beijing judges the US is too divided or polarised to respond effectively, perhaps just after the November 3 presidential election, especially if it is disputed in the courts, this may be the time for Beijing to make some military demonstration regarding Taiwan. This is unlikely to be invasion but it could involve blockades or dangerous missile firings.

The US is still superior to China militarily. But Beijing has a couple of advantages. As one wag puts it: Washington concentrates on platforms, Beijing concentrates on weapons. Beijing’s vast military build-up has been designed overwhelmingly to hit US vulnerabilities with swarms of weapons — missiles or autonomous weapons systems, often guided by artificial intelligence, which would massively raise the cost of any effective US action.

Beijing would be tempted to gamble on the idea that the US no longer had the will or the allies to take effective counteraction.

Those who would analyse China would do well occasionally to actually listen to what its leaders say. Xi has often told his people that the future is one of constant struggle.

At the same time, the Beijing leadership has no history of taking irrational strategic gambles. The highest objective of Western strategic policy therefore should be to continue to make sure that the biggest strategic gamble for Beijing would be irrational, would involve unacceptable risk.

For Australia, there is no holiday from history on offer. There is no need to panic. The Morrison government has done well in handling each trade issue on its merits while defending core national interests. But there are immensely troubled days ahead.

Australia’s China boom is coming to an end. The shuddering crisis in Australia/China relations this week — the worst since the Tiananmen massacre of 1989 — bears one clear message: Beijing will not allow Australia to continue to grow rich from its relationship with China unless we conform our strategic and political personality to Beijing’s wishes.