Anthony Albanese’s decision to launch his campaign in the Opposition Leader’s suburban Brisbane seat was hailed as a “bold opening salvo” by Guardian Australia.

More objective observers familiar with the Prime Minister’s character might describe it as hollow chest-thumping from a leader inclined to be too cute by half.

Malcolm Fraser wouldn’t have given a second glance at Gough Whitlam’s western Sydney seat of Werriwa a half-century ago.

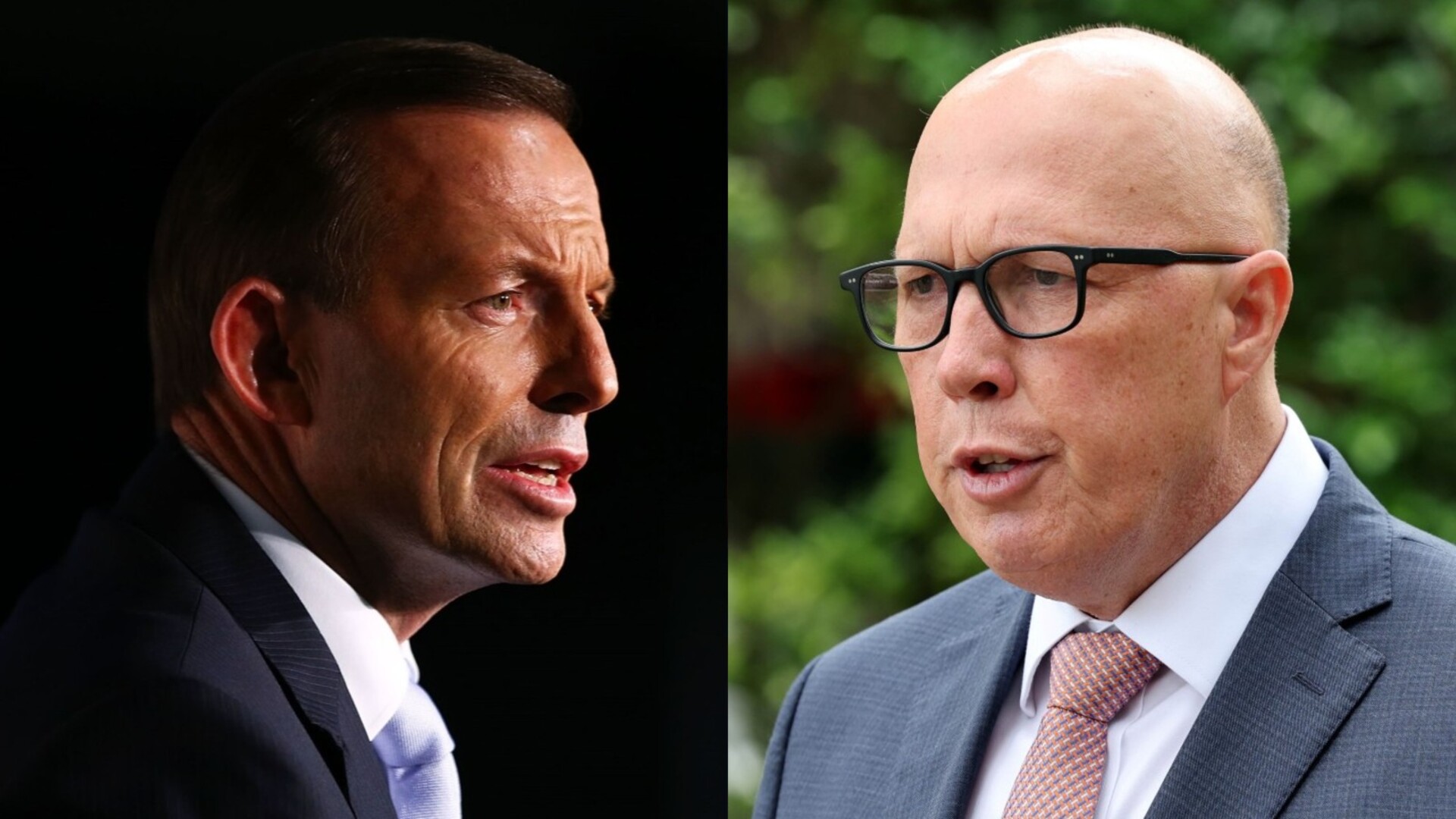

The seat was still off-limits for the Liberal Party in 2013. Tony Abbott worked hard to win the neighbouring seat of Lindsay but knew better than to waste his time on Laurie Ferguson’s patch. Yet Werriwa was where Peter Dutton spent much of day three of the campaign, standing alongside Sam Kayal, the Arabic-speaking son of Lebanese migrants, who is representing the Liberals for the second time.

Labor’s Anne Stanley won comfortably three years ago, increasing her margin to 11.6 per cent. This time, however, she’s in strife. In the great inversion of Australian politics that began under John Howard, Werriwa’s moment has come.

The loss of six blue-ribbon seats to the teals in 2022 was a reminder that the inversion works both ways. Robert Menzies’ former seat of Kooyong was once the kind of safe seat ambitious young Liberals would fight with bare knuckles to win. Even if the Liberals win the seat back from the EQ-challenged Monique Ryan in May, the words safe and Kooyong are unlikely to appear in the same sentence any time soon.

The big reversals in Labor’s class war began with Howard’s landslide in 1996, with wins in seats such as Lindsay, Hughes and Lowe in western Sydney and McEwen and McMillan in Victoria.

Boundary changes have muddied the waters, and fortunes have ebbed and flowed, but the long-term trend is unmistakeable. In 2013, David Coleman won the western Sydney seat of Banks for the Liberals for the first time in the Abbott landslide. He set up his electorate office a street away from the Revesby Workers Club with its giant hammer and sickle embedded in the wall. This time, the best Sportsbet will offer on Coleman is $1.05.

The same parsimonious odds apply to Melissa McIntosh in Lindsay. In the space of two terms, McIntosh has turned a once-bellwether seat into an impregnable Liberal stronghold.

Punters with an appetite for risk will find richer pickings in Bradfield on Sydney’s middle north shore, where Liberal frontbencher Paul Fletcher is hanging up his spurs. Fletcher retained his seat in the Abbott landslide with a margin of 30.8 per cent. Last time, he was lucky to hang on after a determined challenge from the political wing of the renewable energy industry, or teals as they’re known for short. On Sunday, Sportsbet was offering $1.75 on the Liberals’ Gisele Kapterian and $1.95 on Nicolette Boele, a Killara High School graduate, mum of two and climate finance professional from teal central casting. As the NSW Office of Responsible Gambling is constantly reminding us: is this a bet you really want to place?

That Dutton has a chance of becoming prime minister three years after a cataclysmic defeat boils down to three things: shoddy government, disciplined opposition and a household recession.

The recession is hardly apparent at Harris Farm Markets in Willoughby’s High Street, in Bradfield, where the median family weekly income was $3150 in the 2021 census. Mortgage stress? Not much. In these old-money, rugger-bugger suburbs, 36 per cent own their homes outright. Fuel prices? Only 25 per cent drive to work and 52 per cent of Bradfield’s workforce worked from home at the time of the 2021 census. Carnes Hill Marketplace, 40 minutes’ drive west of the Sydney CBD, is a better place to assess the human cost of 14 mortgage rate rises and rampant energy prices.

The shopping trolleys emerging from Woolworths tell the story: heavy on bakery and value-pack sausages, light on salami and prosciutto. Almost no one is lingering for an iced chai latte at Gloria Jean’s.

Meanwhile, Kayal has been finding plenty of takers for his campaign leaflet. Across the first days of the campaign, a steady stream of locals stop to share their thoughts on Albanese and Labor. None could be described as remotely complimentary.

Why would they be? Werriwa is the kind of place people move to in the hope of getting a toehold in the housing market, to send their children to affordable non-government schools and find work in the surrounding industries, which these days are dominated by warehousing and logistics.

Fuel prices matter for business owners and workers, half of whom rely on a car or truck to get to work. Dutton’s promise to cut fuel excise by 25.4 per cent was precisely calibrated for seats such as this.

The deal breaker, however, is housing. In the past decade, families have moved to suburbs such as Austral, rezoned from rural to urban development in 2013, as part of the NSW government’s South West Growth Area.

Austral didn’t exist for census purposes in 2016. By 2021, however, it had a population of 6847, mainly families, and an average age of 31. Fifty per cent had taken out mortgages, with average monthly repayments of $2535. After three years of Labor, the average monthly repayments would now be close to $4000. The median family weekly income, $2224 in 2024, has not caught up.

The number of cars in the driveway has barely changed, not for display but out of necessity; 65 per cent of homes had more than one. Since this is a thoroughly aspirational suburb, half of children go to non-government schools. These families have invested well. Austral will be prime real estate once the Western Sydney Airport precinct is completed.

In the meantime, they have to deal with the inconveniences that come with a new suburb: no public transport, the nearest children’s park is several kilometres away and the congestion on 15th Avenue means it can add 40 minutes to the daily commute.

It doesn’t take much imagination to understand why there’s a queue seven cars long for the bowsers at Costco in nearby Casula, where E10 cost $1.66 – 40c cheaper than the Edgecliff BP. Just 45km west of the Sydney CBD feels like a completely different planet.

The iron law at this election is that where competition for cheap fuel is most intense, Dutton’s stocks increase. At least a half-dozen NSW and Victorian seats, which the Coalition has never held before, are now in play.

The odds are that Dutton will fall short of the 22-seat target he needs to form a majority government. Win or lose, however, 2025 is shaping up to be a strategic triumph, re-establishing a new Liberal heartland among the people Labor forgot.

Nick Cater is a senior fellow at the Menzies Research Centre.