Last month Dave Sharma’s successful preselection for a vacant Liberal Senate seat surprised many, but it offered a clear snapshot of a wider pattern of Liberal parliamentarians being driven out of inner-city electorates, seeking refuge in other places.

What has changed? The key to answering that question is to remember the best Labor and Coalition governments of the past secured and held on to power by pitching their appeal beyond their natural constituencies.

The first nationally elected Labor government in the world was formed thanks to Andrew Fisher, Billy Hughes and others convincing the electorate that the ALP was not just the party of the working classes but the best qualified to govern for all Australians.

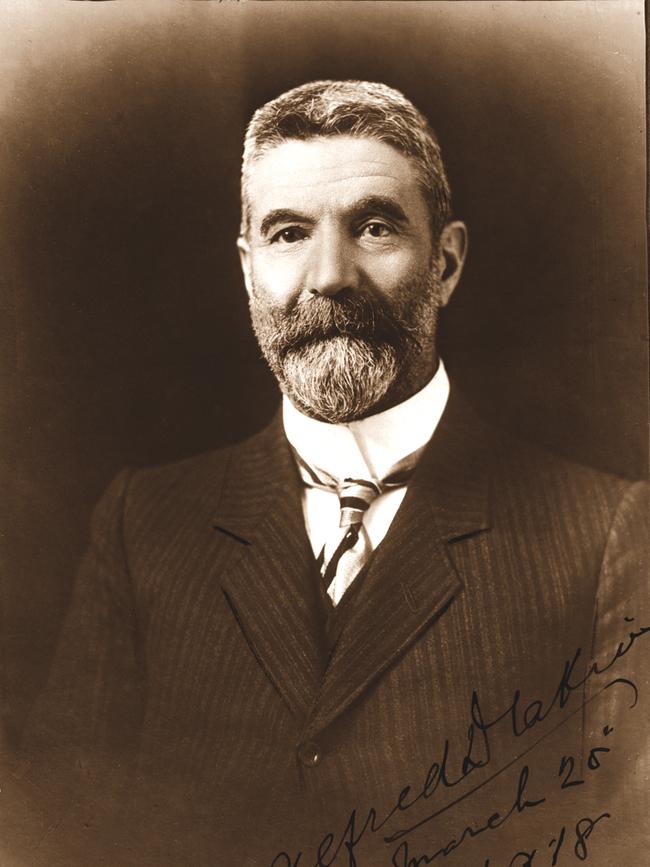

Robert Menzies’ Liberals were, like Alfred Deakin, George Reid and others before him, an even broader church. They drew an explicit contrast to their Labor opponents, saying they were best placed to govern for the whole nation, not just one sectional interest within it.

But it has become increasingly difficult for all parties to manage heterogeneity and deliver different messages to different parts of the nation. It’s the narrowly focused, far more sectionally representative parties and candidates – Greens, teals, One Nation – that have prospered as the support for major parties has eroded. This is partly because of the rise of social media and other technologies of instantaneous communication.

Something a rural MP says in the morning can travel like wildfire so that by 5pm the inner-city party leader has to shut it down. This integration of different publics is growing only tighter, making the national conversation strangely claustrophobic.

Simultaneously, the nation itself has become more polarised. The Indigenous voice referendum demonstrated the degree to which we have become a nation of two halves, divided in attitudes, ethos and world views. One half follows the agenda set by the well-educated cosmopolitan, high-income, inner-urban dwellers; the other half largely consists of outer suburban and regional heartland Australia.

One hundred and eighty years after Benjamin Disraeli famously coined the phrase “two nations” to describe the distance separating rich and poor in industrialising England, we have our own two nations problem. Two hemispheres of a single polity now regard each other with open resentment and suspicion.

There’s a perverse historical irony at work here as well. Labor, the original party of the working class, is finding itself alienated from lower income, high school educated ordinary Australians. The new Liberal heartland is the battler belt – outer suburbs and regions. Peter Dutton clearly understands this, declaring: “The children of the Howard battlers are going to want to find a home with us.” This invocation of the Liberals’ most totemic and successful modern leader is telling.

John Howard’s 1996 election victory was the first time the Coalition claimed a majority of the blue-collar vote. Howard identified the tradies, the regions, the strugglers and the ordinary suburbs as the new “forgotten people”. Unlike Menzies’ original forgotten people of 1942 they were not primarily middle class. They had less education and income, not more.

Since 1996, the Liberal Party has achieved government when these new forgotten people feel their values, aspirations and interests are of paramount concern.

At the same time, however, Liberals increasingly have been crowded out of the voting preferences of the university-educated inner-city middle classes – as Sharma, Josh Frydenberg and others can attest. In two-party-preferred terms these voting cohorts, whose electoral weight has risen with the pervasive spread of higher education, have been gravitating towards Labor.

The leader who can take greatest credit for this historic shift is Gough Whitlam. It was Whitlam as party leader in the 1960s who drove through the modernisation changes that dramatically broadened Labor’s appeal beyond the socially conservative, traditional working-class voter.

It is this, along with the historic It’s Time! election victory in 1972, ending 22 years in the wilderness, that substantiates Whitlam’s claim to be, if not Labor’s greatest post-war prime minister, probably its most significant.

Blue-collar voters had ceased to be the majority in Australia in the ’50s. Whitlam, the Canberra-raised barrister with the bulging suitcase full of new policy ideas, appealed to the rapidly growing middle class. Thanks to Menzies’ reforms, the baby-boomer cohort was the first generation to enter universities in huge numbers, and to these Whitlam’s appeal was honed to perfection.

For a significant minority of this tertiary-educated, baby-boomer coterie, Whitlam’s status as solely beloved leader was only enhanced by the “moral victory” of his catastrophic, “Shame Fraser, Shame” defeat in 1975.

Whitlam’s baby-boomer cohort went on to assume dominant positions in public and corporate institutions. Five decades later, they still set the tone for what preoccupies the public broadcasters and school curriculums. They voted Albo, teal or Green at last year’s federal election, voted Yes for the republic and the voice.

Thanks to a succession of shifts in cultural demographics, media tech, personal choices and political leadership, our two major parties have reversed in striking ways their central cohort allegiances, almost without people noticing.

Both, however, continue to wrestle with the same problem – how to speak to that great heterogeneous beast, the Australian people, in an era when the centrifugal forces are only increasing.

After Disraeli diagnosed Britain’s two nations problem in an era of political tumult and technological change, his genius lay in subsequently fashioning “Tory democracy”, a national vision that appealed across all sections. William Gladstone, too, achieved something similar, with national campaigns that gripped Whigs, Dissenters and ex-Chartist radicals alike. Wily electoral shrewdness combined with principled declarations of abiding values, to the enormous benefit of not just their respective parties but their nation as well.

Whichever house of parliament Sharma and others now find themselves in, the challenge is to begin to craft the means to achieve the same.

Alex McDermott is a freelance historian.

As the centre of electoral gravity shifts for the Coalition, one thing stands out: the good old bankable blue-ribbon Liberal heartland is dead.