The Albanese government, obviously, will not propose another referendum given this fiasco. It will shelter behind the truism that “the people always get it right”.

Peter Dutton, unsurprisingly, has ditched his earlier support for a new Coalition-led referendum, saying the public is “over” the referendum idea for some time. That’s an understatement. The scale of defeat will be measured in the years before constitutional recognition is tried again. That will probably await a new generation.

Indigenous leaders took a historic gamble by demanding a voice in the Constitution – their quest for “substantial”, not “symbolic”, recognition. By tying constitutional recognition to the voice the Indigenous leaders, the Albanese government and the elites who backed this strategy have lost both – no voice and no constitutional recognition. It is a blunder on a momentous scale.

How Indigenous politics plays out defies prediction.

The one certainty is that Aboriginal leadership is going to be more fragmented and divided. The moral victory won by senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Warren Mundine is the start, not the end, of a new chapter of Indigenous reassessment.

Price opposes much of the current Indigenous power structure and, in turn, she is loathed by many senior Indigenous figures, let alone progressive advocates. In her most important post-voice comment she told this paper that Anthony Albanese must now bring Indigenous Australians “into the fabric of this nation” and if the government declines “you can expect that this is what I will challenge them on at the next election”. Most of the changes Price wants are anathema to Labor and its Indigenous MPs.

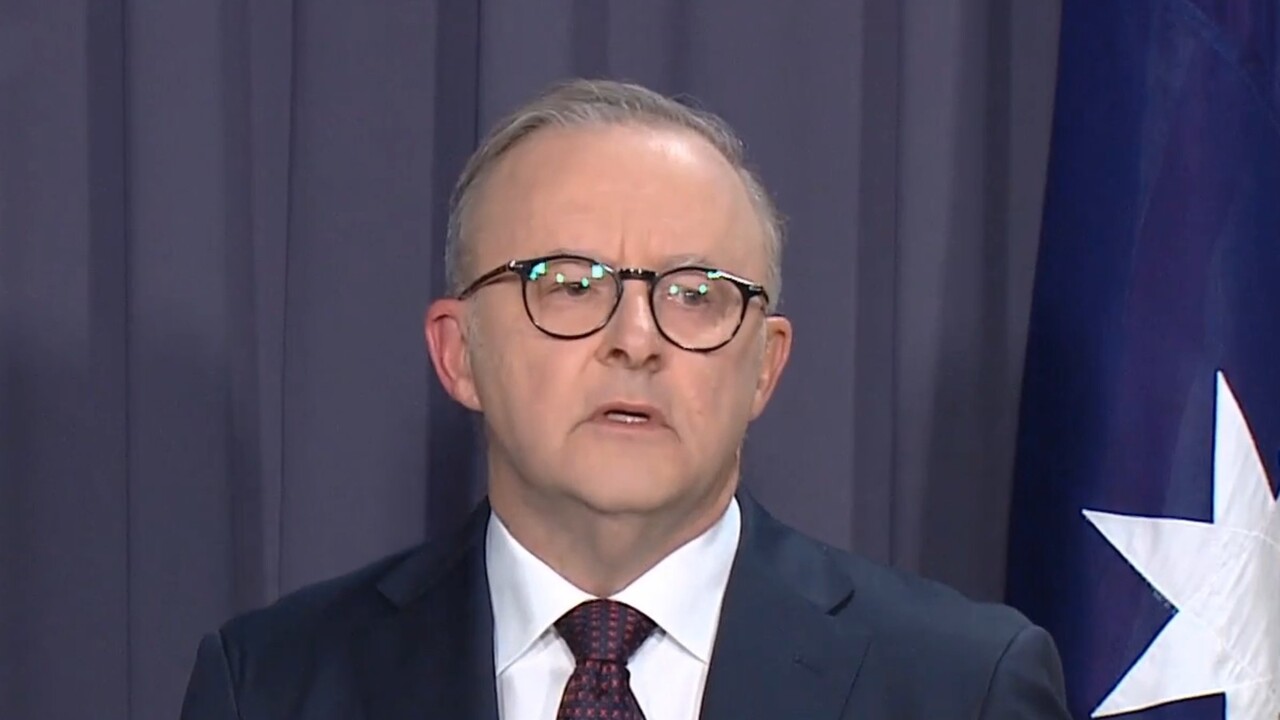

If the Albanese government proceeds on business-as-usual minus the voice it will find its Indigenous policy under challenge. This is already happening with the Opposition Leader and Liberal MPs quizzing the Prime Minister on whether he still supports treaty and truth-telling, given his past solemn pledge to honour the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full.

Dutton wants to wedge Albanese – if Albanese walks away from backing treaty the backlash against him will be furious, but if he does back treaty then the Coalition will say he shows contempt for the sentiment of the Australian public. Labor has got a lot to sort out. Albanese is equivocating and the optics aren’t good. He wants to respect the period of Indigenous mourning and then consult. But which Aboriginal leaders will he listen to and engage?

This referendum will have lasting legacies. The 61-39 per cent defeat is devastating but made worse by several factors. It saw the most intense referendum campaign by a prime minister since Federation. It saw the most substantial alignment of elite and celebrity power for a referendum in our history. It was cast as a moral invitation and a test of the nation’s conscience.

Yet the defeat is one of the worst and, looking at the need to carry at least four out of six states, the No votes in Queensland at 69 per cent, South Australia at 65 per cent and Western Australia at 64 per cent show this proposal was flawed from the outset.

The serial blunders made by Albanese, our elites and the Yes camp reflect a delusional view of Australian values. If the referendum’s advocates fall for their self-serving propaganda that the result was due to disinformation, racism and prejudice they are only likely to repeat their blunders.

Albanese should never have put the referendum in this form. He made a pledge but the notion that the Prime Minister should put to referendum exactly what the Indigenous leaders demanded is an unprecedented idea. No prime minister has previously justified a referendum in these terms.

The model of the voice was contentious – a group rights body based on ancestry – thereby challenging constitutional principle and governing practicality. It was inevitably going to raise issues of equality, race and national division. All this was obvious at the start.

The Labor Party seems to have a dual identity, fluctuating between hard-headed realism and progressive fantasy. The realism was missing throughout this referendum. There was an apparent wilful denial from the voice’s advocates who used a series of moral, emotional and virtue-laden appeals that overlooked the central issue – the proposal was flawed, creating public concerns about a divided nation and constitutional inequality.

Albanese was trapped on the dilemma of bipartisanship. No referendum has been passed without bipartisanship. He needed bipartisanship. Yet the Coalition parties were never going to support the voice in the Constitution. It was opposed by John Howard, Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull as prime minister, the entire Turnbull cabinet that included Scott Morrison and Dutton, and then opposed by Morrison as prime minister.

In March 2021, Morrison said: “It has never been the government’s policy to have that process (the voice) enshrined in the Constitution. That never has been the government’s policy. I think that is pretty clear. It is not the government’s policy.”

The Coalition parties never had any political ownership of a constitutional voice. The reasons for their rejection were clear and usually ignored by the pro-voice media. They were spelt out in 2017 by Turnbull and his attorney-general, George Brandis, notably that the Indigenous voice as a “constitutionally enshrined additional representative assembly” was inconsistent with the “fundamental principle” of “equal civic rights” in Australian democracy.

They said at the time the voice proposal was neither desirable nor capable of being carried at a referendum. Parties cannot walk away from such principles once enunciated. Proponents of the voice were never able to satisfactorily rebut these Coalition enunciated principles. This goes far in explaining the magnitude of the vote against the voice last weekend.

Albanese never took serious steps to explore bipartisanship. That meant the referendum would pass only if Australia had changed as a country and, it seems, Albanese felt that it had changed – that Australia had become a more progressive nation where new, once improbable, vistas had opened up. That was a huge risk.

It flouted the “laws” of referendum politics and grievously misread the sentiment of middle Australia. Labor’s referendum record was one success in 25 proposals since Federation. That had to dictate caution. But it didn’t.

What might Albanese have got had he tried a full-scale constitutional convention? The best would have been a free vote across the entire Coalition parties in return for a substantial watering-down of the voice model. The Indigenous leaders would have vetoed any such effort. And Albanese never contemplated such concessions given his initial supreme confidence that the voice would be carried.

Indeed, Albanese felt the voice’s victory would have two political consequences – it would entrench Labor’s moral ascendancy and it would crush Dutton’s leadership, deepening the Liberal crisis. Albanese saw immense political benefits from this referendum.

The Coalition in office had backed recognition, never the voice. The origins of its rejection of the voice go back years. Any notion that in opposition it would support the voice that it had rejected in government was a forlorn prospect. People who blame Dutton for not supporting the voice ignore the history, the established Coalition position and that Dutton made a superior reading of the country.

So the course was set – a contentious proposal devoid of formal bipartisanship. It became a march to political doom.

The moral is that referendums are national projects needing national cross-party support. They cannot succeed as party political or historical justice projects. There will be no referendum put on the republic for 20 years or for another generation. Labor can forget that cause. The party needs to assess the full ramifications of what it has done.

The Australian tragedy is stark – a majority of people support Indigenous constitutional recognition but this goal is finished for years and almost certainly for decades, the consequence of an epic political mismanagement.