Beijing is ferociously opposed to AUKUS, which the Albanese government remains rhetorically committed to. But apart from the fixed strategic settings it inherited, and Wong’s minimal but valuable comments, Labor is doing bad things Beijing wants it to do.

These are: expelling intelligence chiefs from cabinet’s national security committee; restricting and possibly soon abolishing the Australian Strategic Policy Institute; never now mentioning China as a justification for AUKUS and nuclear-powered submarines; and doing nothing for military capability in the decade ahead.

The CCP has long experience variously intimidating, manipulating, punishing and rewarding the Labor Party. It doesn’t always succeed. When Malcolm Turnbull was prime minister the Coalition government attempted to ratify an extradition treaty with China. This would have been disastrous. Labor, under Bill Shorten’s leadership, agonised over what to do but decided rightly to oppose ratification, which then failed.

Senior Chinese officials told the Labor leadership Beijing would campaign against the ALP among the diaspora Chinese community if it opposed ratification. Labor stared down this threat and the Liberals, like any responsible government, found it had so many disagreements with Beijing that the electoral intimidation of Labor became moot.

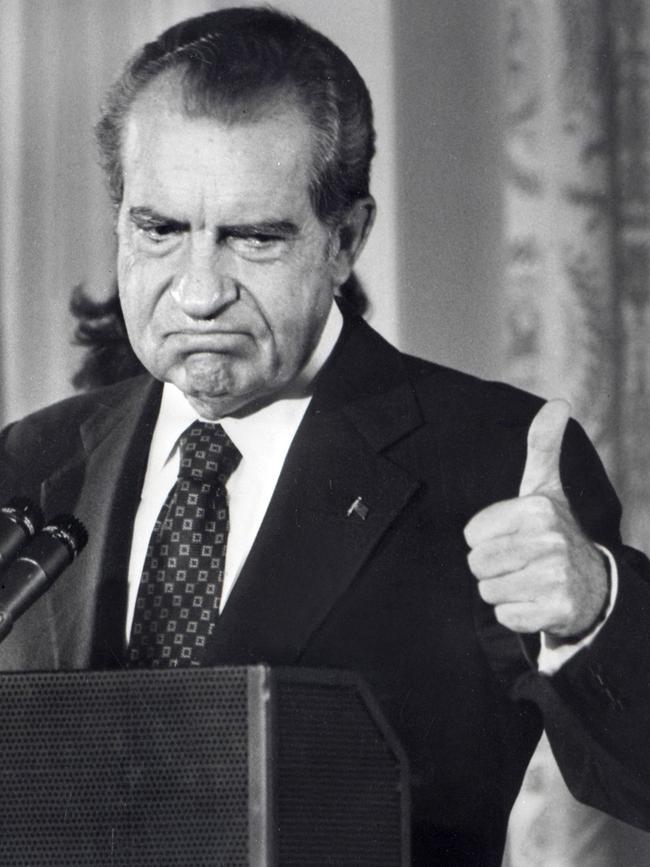

A reverse example was Beijing’s exploitation of Gough Whitlam’s trip to China as opposition leader in 1971. Once US president Richard Nixon moved towards diplomatic recognition of China all of the Asia-Pacific followed suit. Whitlam did nothing remotely innovative in establishing diplomatic relations with Beijing after he took office. A Liberal government would have done the same. But Beijing presented Whitlam, an overbearing, poorly informed and unpopular figure in Asia, as former Singapore prime minister Lee Kuan Yew’s memoirs make clear, as a political genius in opening to Beijing.

The Albanese government, unlike any previous Labor government, is dominated by Labor’s Left. They are perfectly patriotic Australians who generally want to do the right thing by national security but have no instinctive feel for the issues. They recognise the electoral importance of national security credentials and went along with AUKUS, nuclear submarines, the Quad and of course the US alliance.

The vaguely hawkish Richard Marles has little influence in the government and has delivered absolutely nothing for defence.

Anthony Albanese, in confirming the strategic settings he inherited, started off well and greatly annoyed the Chinese. Now they’ve given him “stabilisation” in the relationship and slowly dole out modest rewards, the next to be a visit from the Chinese Premier, in exchange for good behaviour.

Former prime minister Paul Keating is the Chinese government’s most high-profile, enthusiastic public backer. As well as attacking Albanese and Wong, he frequently attacks Australia’s intelligence agency chiefs, describing them as having gone “troppo”, behaving deceptively, manipulating politics etc. These men and women are forbidden to answer such attacks or defend themselves. The government’s defence of them is pathetically rare and mealy-mouthed, never more than an isolated line by one or other designated minister.

Now comes news that ASIO head Mike Burgess and Australian Secret Intelligence Service head Kerri Hartland will no longer routinely attend NSC meetings. For the first time the NSC has as a permanent member Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen and his departmental head. It also, I think for the first time, includes a non-cabinet minister, Pat Conroy, a junior minister who divides his time between defence industry and the Pacific.

Climate change is important but you could just as easily make a case to include the education, health or industry and science ministers in the NSC. You could link all those ministers to national security. But ASIO and ASIS are centrally concerned with the sorts of things the NSC considers routinely, much more so than the Climate Change Department head.

ASIO has a formal policy advice role as well as intelligence collection and threat analysis, and is tasked with providing regular briefings to the opposition. The ASIS boss knows every public and secret thing that Australia knows about every contentious international matter. Not wanting them in the room is insane.

Turnbull in his memoirs entertainingly recalls a typical, though obviously imaginary, briefing from former ASIS boss Nick Warner along the lines of: “I have just returned from a clandestine meeting with the chief assassin of the Ruritanian Intelligence Service. We met in an ancient cellar underneath the Casbah in Tangier …” The serious point is that the ASIS boss is necessarily among the worldliest and most sophisticated of people who actually knows what’s going on.

The ASIO and ASIS bosses will be called into NSC when an agenda item directly and explicitly concerns them but won’t be there generally. Not wanting that experience and expertise to be on hand when decisions are made is crazy. The director of the Office of National Intelligence is now the only intelligence chief regularly at NSC meetings. This move has to be seen as diminishing the role of the intelligence chiefs, just as Keating, and Beijing, wanted.

It’s also part of a wider syndrome of the Albanese government trying to suppress debate by suppressing information in the national security sphere.

This particularly concerns ASPI. The abolition of ASPI was one of Beijing’s 14 demands of Australia at the height of its wolf warrior diplomacy. It now looks as though the government is getting ready to kill ASPI. It has moved ASPI’s funding from a four-year to a biennial cycle, which makes it impossible for ASPI to plan properly. It has stopped replacing retiring ASPI council members. And it has commissioned an inquiry by Peter Varghese, an independent thinker who will make up his own mind, into federal government money going to think tanks to subsidise research.

ASPI was set up nearly a quarter of a century ago by the Howard government to provide contestability in defence policy and public debate. Having recently lost Peter Jennings, Michael Shoebridge and Marcus Hellyer, ASPI is a shadow of its former self. But the government still hates the idea that its waffle and often misleading platitudes in defence are picked apart by independent analysts at ASPI.

The Defence Department has been demanding that ASPI show its research and analysis pieces to Defence before it publishes them. But ASPI’s inconvenient independence is critical to the huge value it has added over decades. Because ASPI is a think tank rather than an academic body, its output is crisp, policy focused and has often had impact.

Defence documents are intentionally indecipherable. Defence hates having its equivocations, failures and general messiness exposed to proper scrutiny. The government despised ASPI’s last defence budget analysis.

If the government does destroy ASPI, it will greatly impoverish public debate. It will comfort the government by making sure there are fewer public voices to call out its preposterous non sequiturs. But it will please Beijing. No doubt there’s a reward in that.

The Albanese government is taking a series of disturbing actions in national security, effectively implementing an agenda that the Chinese Communist Party wants for Canberra. The picture is mixed, of course. Foreign Minister Penny Wong importantly outlined publicly a series of specific disagreements Canberra has with Beijing.