Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad welcomed it. President Isaac Herzog said the ICC had “chosen the side of terror and evil over democracy and freedom”.

The warrants lend the authority of international criminal justice to the goal of delegitimising Israel but are unlikely to lead to the arrest of Netanyahu or Gallant anytime soon. Their initial impacts will be to undercut efforts to produce peace through negotiations, delay the release of remaining hostages and obstruct the goal of eradicating Hamas as Gaza’s governing power. They will not increase aid delivery and food supplies.

The wider impacts will be to undermine every country’s right to self-defence against armed attack while validating the triple tactics of barbaric terrorism by death squads, hostage taking and mass slaughter of civilians exploited as human shields.

They will leach support for the already troubled ICC project by eroding its legitimacy in some countries and convert neutral indifference into hostile opposition in others.

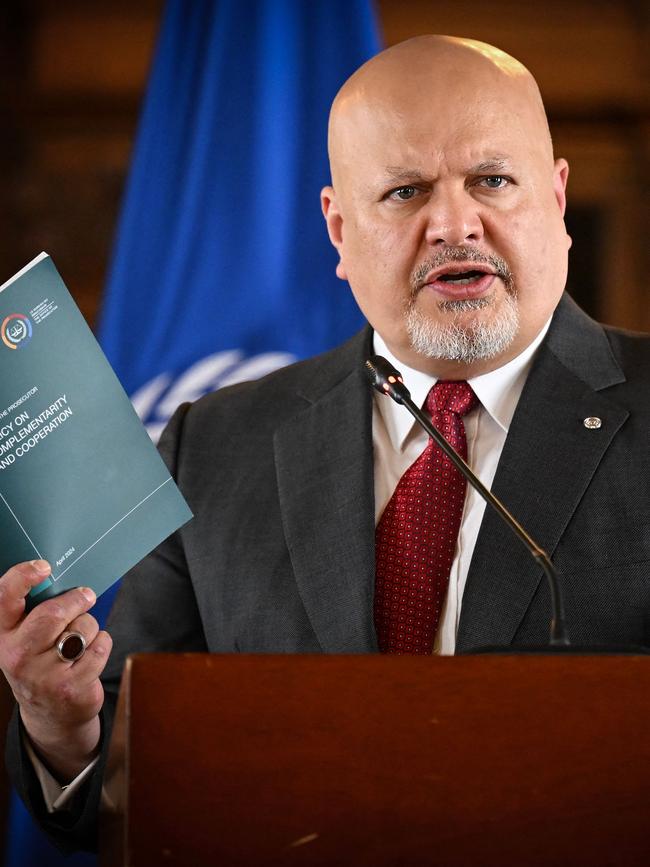

There are other troubling questions on the procedural soundness of the warrants.Karim Khan selected members of an expert panel to advise him on the case. Some had personal links to him. Others were on record accusing Israel of the crimes they were asked to investigate.

The ICC wants to arrest, detain and try the head of a government engaged in an existential war of survival against enemies who have sworn to destroy it and ethnically cleanse the region of Jews. With no responsibility for the outcome of a war, it’s hopelessly naive to demand “a state’s military operations be subject to international judicial supervision in the midst of a conflict”, in the words of Oxford University law professor Richard Ekins.

The absurdity of the charges is exceeded only by the malevolent perversity of accusing Israel of inhumane crimes of which it was the victim on October 7, with Hamas promising to repeat them “again and again”. How many charges are based on dubious Hamas sources? The court resurrects the charge of mass civilian deaths by starvation that has been debunked by the Famine Review Committee. There’s no acknowledgment of Gaza’s low ratio of civilian-to-combatant deaths in the history of urban warfare.

The ICC has jurisdiction over member states. Israel is not a member. Gaza is not a state. The Palestinian Authority, seeking ICC intervention, is neither a state empirically nor exercises meaningful sovereignty over Hamas-ruled Gaza. In joining the ICC, it tried to circumvent the 1993 Oslo Accords in which it promised not to exercise criminal jurisdiction over Israeli nationals.

The court’s jurisdiction over member states is based on complementarity. The principle authorises it to step in only when national authorities are unable or unwilling to investigate and prosecute.

Democratic Israel’s independent prosecutors were not given the opportunity to investigate the alleged crimes before the ICC acted. Israel’s powerful judiciary has the will and ability to hold officials accountable. In 2015 former prime minister Ehud Olmert was convicted of bribery and obstruction of justice and spent 18 months in jail.

Cardinal George Pell’s case proved the vital importance of multiple layers of the judiciary. Yet there’s only one court, with variable standards of judges’ professionalism and apolitical independence, to decide international criminal trials.

All 124 ICC member states are legally obligated to arrest the two Israelis should they set foot in their country. But here’s a thought. Donald Trump could quietly invite Netanyahu to his swearing-in in January. If Netanyahu agrees, they can make a joint announcement. After taking office, Trump can consider sanctions on ICC personnel and any country that arrests Netanyahu.

Anthony Albanese’s silence has been disappointing but not surprising. But this is an opportune moment for Australia to withdraw from the ICC. Peter Dutton should commit to do so. It’s unlikely to be a vote loser.

Ramesh Thakur is emeritus professor at the Crawford School, Australian National University and a former assistant secretary-general of the UN.

Last week the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former defence minister Yoav Gallant. Israel bitterly criticised the decision as anti-Semitic slander.