While being mooted as a possible ambassador to Washington, in 2022, Rudd complained that he seemed to be getting steadily demoted: from prime minister to foreign minister to ambassador.

Nonetheless, he accepted the appointment. Perhaps, given his longing to be able to speak publicly as a private China scholar, he is now angling for a further demotion – to, say, reader in Chinese foreign policy at Hong Kong Baptist University.

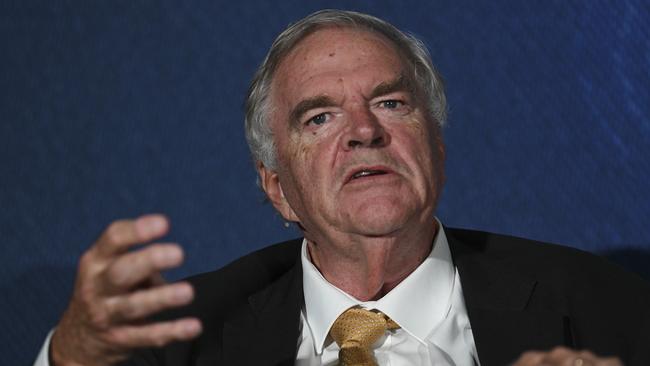

Kim Beazley, a good servant of this country and a highly effective ambassador to Washington (2010-16) before the equally effective Arthur Sinodinos took the job, remarked, rather dryly, that Rudd would find it difficult to subordinate himself to the requirements of being an ambassador rather than an opinionator. It seems he was on the money.

Beazley told Ashleigh Gillon on Sky News last year that he’d found being ambassador to the US “humbling”, after having been defence minister, deputy prime minister and opposition leader before that. Rudd, of course, lobbied strenuously to be put forward as the next UN secretary-general. Being humble is not exactly his style.

His remarks in Honolulu were certainly policy oriented, not just matters of arcane scholarship. He observed that Xi Jinping was determined to subordinate Taiwan to communist rule and was devising ever more comprehensive strategies to bring it to heel short of all-out war.

What, he asked, did the US and its allies, and Taiwan, need to do to deter Beijing from pursuing its evolving set of coercive and subversive strategies, in the interests of peace across the Taiwan Strait?

He correctly pointed out that Beijing feared both the democratic example Taiwan offered to the people of China and that the international community would come to acknowledge the fact Taiwan was, de facto, an independent state, which, as Tsai Ing-wen, when President of Taiwan, remarked, didn’t need to declare independence because it already was independent.

Beijing, Rudd pointed out, insisted that there be a dialogue directed at achieving a “one China” agreement based on the so-called 1992 Consensus. Whereas the Taiwanese government has been tactful enough to declare that the status quo – de facto independence – suits it, Xi rejects the status quo. He is intent on “reunification” on the basis that Taiwan is an inalienable part of China and the Communist Party is the sole legitimate government of China.

Perhaps uncomfortably aware that a full-scale invasion of Taiwan would be a risky and costly operation, Rudd remarked, Xi had been ratcheting up grey-zone activities and subversion of Taiwanese politics, in an effort to undermine the governing Democratic Progressive Party. As politicians in Taipei remarked very recently, he hoped to induce Taiwanese quislings to impose a “Hong Kong solution” like that imposed on the former British Crown colony under the national security law.

Inviting strategy and foreign policy feedback – as a private scholar – Rudd asked: how we are to deter “China’s emerging menu of strategic measures that remain short of war and short of invasion but which share the same political objective, which is to force Taipei to capitulate?” Given Xi’s evident impatience, he commented, we know that reassurance and dialogue will not suffice.

His ringing conclusion was that any “jaw, jaw” to avoid “war, war” (echoing Winston Churchill) needs to be “part of a much wider equation on integrated deterrence which will command all our efforts for the decade ahead if we are to successfully preserve the peace”.

Now, had these remarks been made by Rudd in his former capacities as prime minister or foreign minister, they would have fully equalled the robustness of remarks made in recent years by several of our other prime ministers (all Liberals, as it happens: Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison).

They might be seen as committing Australia to solidarity with Taiwan, with the US and other concerned regional states, notably Japan, South Korea and The Philippines.

But Rudd is our ambassador to the US. If his speech was cleared with Wong and Anthony Albanese, why did he need to declare that he was taking off his ambassadorial hat and speaking as a private scholar?

If he changed hats because the speech was not cleared, what are the policy implications?

Such questions are all the more pertinent because, actually, Rudd’s remarks were commonplace. There were no particular insights or recommendations from a scholarly or a strategic point of view that would single the address out as significant. What, therefore, was the point of the thing, other than Rudd’s addiction to seeking the limelight?

As one of Australia’s most distinguished China scholars remarked to me and other specialists on the subject last weekend: “This is just classic Rudd: stating the obvious, asking for greater understanding of Beijing’s position and signing his name to an unspecified set of measures said to ensure we all sleep well.”

Rudd was a private scholar, or at least think tank figure, before taking up the ambassadorship. That think tank was the New York-based Asia Society. In January 2021 he became president of the Asia Society after six years directing the society’s policy arm, the Asia Society Policy Institute.

Several of the institute’s board members with close ties to Beijing helped put Rudd at the head of it from the time it was set up, in 2015: businessman Ronnie Chan, Hainan Airlines Group’s Chen Guoqing and Blackstone Group founder Stephen Schwarzman. They placed Rudd as the president of the institute on a top-of-the-range salary package for non-profit executives in the US.

While at the Asia Society Policy Institute, Rudd consistently criticised Australia’s Coalition government and the Trump government’s China policies while seemingly avoiding any criticism of Xi or China. He maintained a social media presence in China with more than 600,000 followers, in which he would assail Turnbull but never Xi. How tactful and adroit of him.

It must be assumed that when, in late 2022, the Albanese government appointed Rudd to Washington in place of Sinodinos, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the intelligence agencies and cabinet were all aware of his track record at the Asia Society and its Policy Institute, as well as his social media activities inside one of the most totalitarian societies on the planet. Yet he was sent to represent us in the capital of our indispensable ally.

Simply as citizens of this country, we were far better served by Beazley and Sinodinos. Simply in terms of the challenge China embodies to Indo-Pacific and international order, we need good representation in Washington. Simply put, it’s time Rudd was released from his ambassadorial duties and put out to pasture with friends in Beijing.

Paul Monk is a former head of the China desk in the Defence Intelligence Organisation, a specialist in international relations and the author of a dozen books, including Thunder From the Silent Zone: Rethinking China (second edition, 2023), The West in a Nutshell (2009) and Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018).

Last week, presumably given clearance by Penny Wong, Kevin Rudd gave a speech at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Centre for Security Studies in Honolulu about China, Taiwan and deterrence. He went out of his way to make clear that he was not speaking in his capacity as Australia’s ambassador to the US but in a private capacity as a China scholar. Really? How does that work?