The NAA is vital to the health of our democracy, but it is languishing under systematic obstruction by other parts of government. To reverse the NAA’s decline, a shake-up of how security agencies interact with the National Archives is required.

Most commonwealth records are handed to the NAA after a certain number of years, depending on the nature of the material. National security and defence information, including cabinet material, is often retained by agencies for the longest period due to its sensitivity.

A growing portion of the NAA’s collection comprises unread material pending review to determine its contents and if it can be released. Many researchers need to request specific material to be examined before they can access it. I have requests dating back to 2018 for material that is still pending examination. This is not uncommon for those seeking access to defence or national security records and this is not really the fault of the archives.

While the NAA is the custodian of the commonwealth’s archival material, it cannot decide to declassify records on its own. For national security and defence material, in particular, it requires the expertise of those agencies to determine whether or not the release of past records could, for example, damage a foreign relationship, compromise an intelligence source, or reveal a military secret.

The result is that if the agency or department which created the record simply ignores requests from the NAA to assist with declassification, the release of many documents can be forestalled indefinitely. While working in the national security community I saw this first hand as I occasionally had to determine whether or not past records could be declassified.

I recall receiving a document from the Hawke government which had spent almost two years pinballing between officials who were unwilling to claim the document and make a decision. It took 10 minutes for me to determine there was no risk associated with declassifying the document and sign off on its release to the poor researcher who had requested it two years prior.

The episode highlighted to me that there is no practical incentive for officials to support declassification and no real penalty for simply shunting requests from the NAA on to someone else’s desk. A culture of risk-aversion and apathy has resulted in disregard by many officials towards the transparency that the NAA is charged with providing.

The incentive to declassify past secrets needs to be flipped to restrain excessive secrecy. Instead of the current default that unexamined records remain classified, they should be automatically released if agencies fail to examine them and substantiate a case for keeping them classified. This change would force agencies and departments to properly resource the declassification process and assist the NAA.

This change is increasingly important as security agencies are seeking legislative amendments to further constrain what the NAA can release to the public.

A current bill before parliament seeks, among other things, to exempt Australian Secret Intelligence Service and ASIO records from the Archives Act where the identity of ASIS and ASIO staff or sources could be “inferred” from such records.

The identities of covert intelligence officers and their sources should always be protected, not least of all because many undertake this work for Australia trusting it to remain secret forever, even from their families. However, the current system provides little real recourse for anyone, including the NAA, to contest agencies’ secret deliberations to withhold records on the basis of what might be inferred from them. The scope for risk-averse officials to err on the side of claiming an exemption where it mightn’t apply is ample.

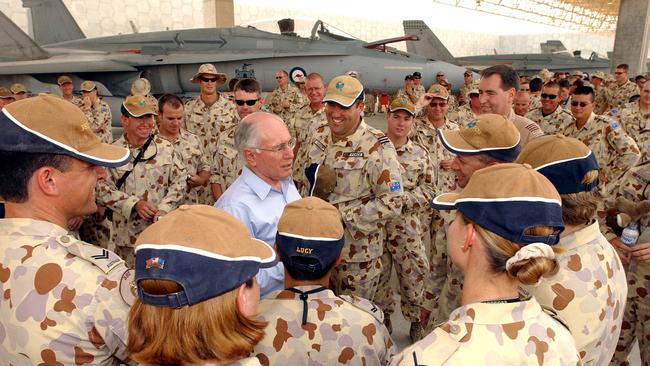

In the meantime, the apparent decision by the Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet to withhold from the NAA cabinet papers concerning the Iraq War is a frustrating obstruction of the archive’s work. Among the excuses reported is that DPM & C declined to transfer the cabinet material to the archives because they were being retained as part of an official history project concerning the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Official histories are no substitute for giving Australians direct access to the original material.

Official histories are a useful tool in performative transparency. They allow governments to declare that new light is being shed on past decisions. What remains unknown, however, is which material was omitted from view and how firmly officials held the editorial pen over historians.

The departments of defence and foreign affairs have sponsored history projects to give Australians accessible accounts of past military operations and diplomatic activities.

More recently, our intelligence agencies have begun commissioning histories of their own, including a multi-volume series on ASIO. ASIS has prepared a draft history that remains unpublished. Meanwhile, the Australian Signals Directorate abandoned an initial book on its own story to be authored by eminent historian John Blaxland.*

These projects are doubtless useful to scholars, but they are not independent pieces of research, nor are they always prepared to an academic standard. They are, by intel agencies’ own admissions, PR exercises designed to assist recruitment and encourage public support for their work.

Real openness would be supporting a declassification process that withholds records only on the basis of absolute necessity, not bureaucratic indifference.

Certainly, efforts by civil servants to shape public narratives concerning their own past would be better regarded if those same officials weren’t also appearing to engage in procedural neglect of archivists’ efforts to make unvarnished records accessible for us all.

William Stoltz is an expert associate at the ANU National Security College.

*Correction: The original version of this column wrote that the Australian Signals Directorate abandoned its official history. The ASD published volume one of its official history, The Factory, in February 2023, after terminating an initial commission with historian John Blaxland in 2020.

The recent mishandling of the Iraq War cabinet records offers a glimpse into the national security community’s apathy towards the National Archives of Australia, an institution that applies essential transparency to the conduct of these otherwise faceless officials.