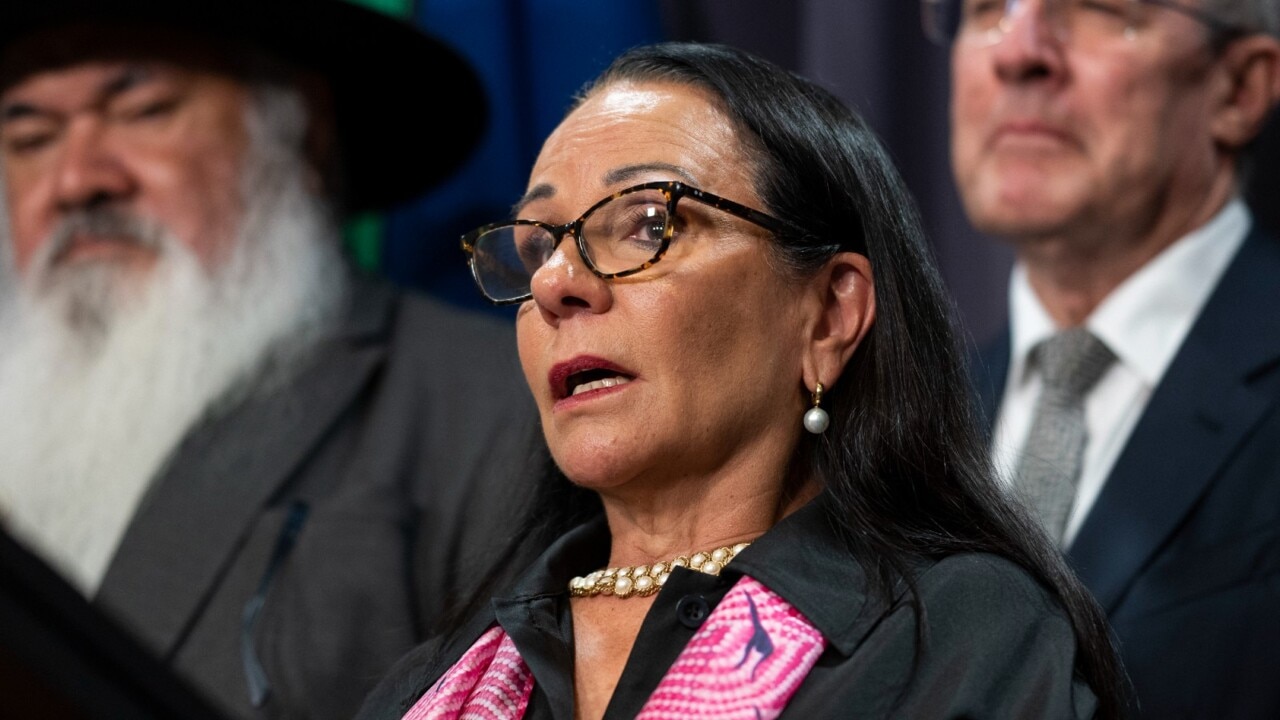

Indigenous voice to parliament can complete the unfinished business of the 1967 referendum

The 1967 referendum was not only Australia’s most important referendum since Federation, it was also the most successful. The proposal swept the nation, winning every state and achieving a national Yes vote of 90.77 per cent.

There are lessons from 1967 for the voice referendum, starting with their similarities. Both votes concern inclusion and recognition for Indigenous peoples. Both also arrived at the ballot box after a lengthy period of grassroots activism.

The 1967 referendum emerged after decades of agitation for constitutional change to recognise the basic humanity of the nation’s first peoples. The voice proposal has its roots in the recognition movement of the late 1990s before being called for in the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 2017.

There are also significant differences that explain why the voice is on a different trajectory. The 1967 referendum was backed by a community and political consensus that law reform was essential to achieve justice for Aboriginal peoples. The ban on Aboriginal people voting in federal elections put in place in 1902 had been removed in 1962. A sense had also emerged that national laws were needed to protect the interests of Aboriginal people. The Constitution was obviously discriminatory and out of step with Australian values. It needed to be changed.

The changes made in 1967 were technical and narrow, and provided no recognition to Indigenous peoples. Section 51(xxvi) had empowered the federal parliament to make laws with respect to: “The people of any race, other than the Aboriginal race in any state, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws.” The 1967 referendum deleted the words in italics. It also repealed section 127, which provided: “In reckoning the numbers of the people of the commonwealth, or of a state or other part of the commonwealth, Aboriginal natives shall not be counted.”

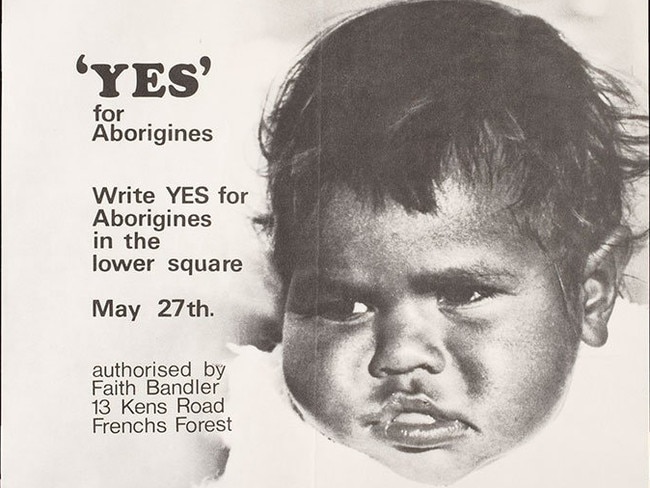

The 1967 campaign focused upon emotion and values, with little examination of the changes or on lawyers’ interpretations of their effect. Instead, people spoke of how the referendum would achieve equal rights and citizenship for Indigenous peoples and ensure our nation’s founding document treated them as human beings. The imagery of the campaign told a similar story, with one front-page newspaper photo summing up the mood in showing two children, one Aboriginal and one white, gazing happily at each other as they walked down a laneway hand in hand.

Every major political party and leading community figures supported the change. The unique national moment was reflected in the fact that no one in parliament voted against the proposal and as a result there was not an official No case. Letters to the newspapers ran almost unequivocally in support. Where there was misinformation, it was not amplified by politicians, nor by the media.

Another positive break for the Yes case was that a second referendum question was put to Australians on the same day. The government also sought to break the “nexus” between the House of Representatives and the Senate that requires the House to be, as near as practicable, twice the size of the Senate. Prime minister Harold Holt, supported by opposition leader Gough Whitlam, wanted to do away with this so the House could be increased without a corresponding change in the Senate.

This second proposal attracted the lion’s share of the political debate, and almost all of the disagreement. Even though it had bipartisan support, it was opposed with great effect by a small group of senators. They proved to be brutally effective in prosecuting the No case by arguing the change was an attack on the Senate and could produce an explosion in the number of lower house members. Their cry of “no more politicians” succeeded, with the Yes case on the nexus proposal winning only one state and a national vote of 40.25 per cent.

Media coverage the day after the referendum focused on the nexus proposal. Holt was bitter about his loss and, rather than labelling May 27 as a win for Aboriginal Australians, described the outcome as a “victory for prejudice and misrepresentation”. He blamed Australians who “chose to ignore the advice of those to whom they normally look for guidance”.

Australians have come to see the true significance of the 1967 referendum. The unprecedented Yes vote for the Indigenous proposal provided a mandate for national laws and policy on Aboriginal affairs. What was missing was positive acknowledgment in the Constitution and a means for first peoples to have a say on the laws and policies that could now be made for them.

The task of the 2023 referendum is to remedy this unfinished business by providing recognition and a voice to Australia’s first peoples.

George Williams is a deputy vice-chancellor and Professor of Law at the University of New South Wales.

Australians last voted in a referendum to improve the lives of Indigenous peoples in 1967. That poll erased racially discriminatory wording from the Constitution and enabled the commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal peoples.