Those tensions are, in many respects, the unfinished business of the 1967 referendum. At their origin lies the almost complete disconnection between the theme that dominated the campaign leading to the vote on May 27, 1967 and the reality of the constitutional amendment to which the referendum gave effect.

The campaign’s theme was unambiguous: equal rights. Nowhere was that aspiration more eloquently captured than in the song that echoed across the country during the referendum – a song urging Australians to “Vote Yes to give (Aborigines) rights just like me and you”. And as Faith Bandler, who embodied the campaign’s spirit, declared, the time had finally come for “the original Australians” to be “treated equally with other Australians”.

Nor were equal rights at odds with official policy.

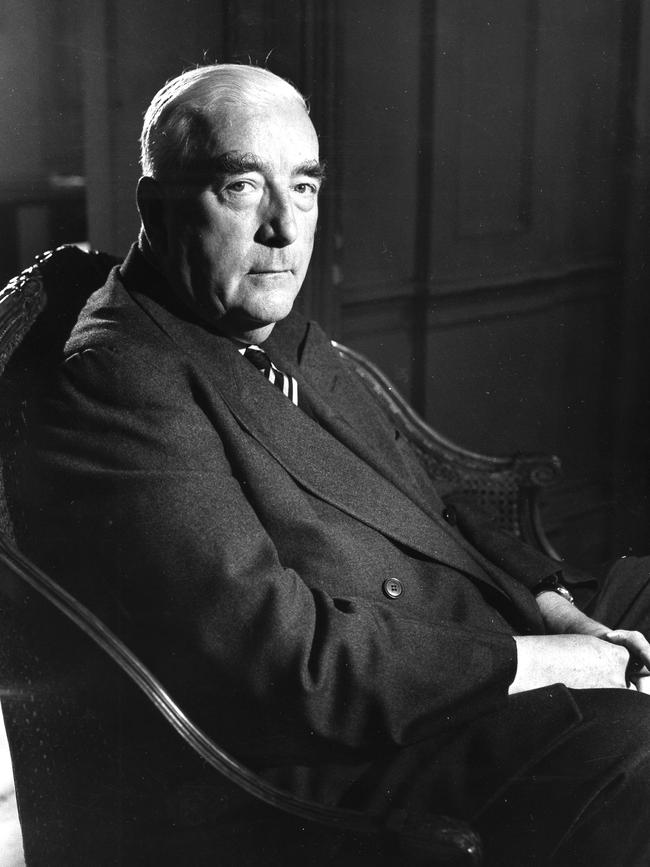

On the contrary, as Paul Hasluck, Robert Menzies’ long-serving minister for territories, told the state premiers in 1961, the government’s overriding objective was for Aboriginal people to be “members of a single Australian community enjoying the same rights, privileges and obligations as other Australians”.

It was that positive vision Australians endorsed when they overwhelmingly backed the proposed change; voters were convinced the referendum would “remove words from our Constitution that many people think are discriminatory”, as the leaflet articulating the Yes case stated. Read literally, that description was correct; but the practical import of the amendment was altogether different.

The relevant change was to the constitutional provision that confers on parliament the power to legislate with respect to “the people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws”.

Initially, the provision excluded “the Aboriginal race in any state”. That limitation, the University of Adelaide’s Professor Greg Taylor has shown, reflected the narrow objective of the provision’s leading advocate, Sir Samuel Griffiths, which was to allow parliament to pass legislation ending the abuses associated with the forcible importation of foreign labourers, notably from the Pacific Islands.

By 1967, Griffiths’ objective had long since been achieved (albeit notoriously harshly), leaving the provision moribund. But the referendum gave it a new lease of life.

Excising the exclusion of “the Aboriginal race” from the provision’s scope, the referendum granted parliament the same powers with respect to Aborigines that it had over other races – including the power to pass legislation that was substantively discriminatory, be it to the benefit or the detriment of those affected.

Everything suggests Australians expected parliament’s new power to be used to further the process of integration: any “special laws”, Hasluck had explained, were to be “temporary measures” designed to “assist (Aborigines) to make the transition” into Australian society.

There was, however, nothing that restricted the amended provision to temporary measures or specified the goal it was to serve. As a result, when prime minister William McMahon suddenly announced on Australia Day 1972 that he was jettisoning the policy of integration, his government could draw on vastly increased powers to pursue its new objective.

Quite what that objective was remained entirely unclear; matters were not helped when the Whitlam government dubbed it “self-determination”, as if the outcome being sought for Indigenous Australians resembled the process then under way in Papua New Guinea. What was clear, however, was that the new approach involved a torrent of special measures.

To say that those measures proved unsuccessful would be an understatement. Moreover, as successive crises tore remote Indigenous communities apart, additional special measures were heaped on those already in place, both squaring the error and perpetuating it. Nor were the three attempts at creating a workable and constructive Indigenous consultative assembly any more successful, with each attempt being even more divisive than its predecessor.

To make things worse, the rhetoric justifying the overall policy underwent a subtle but important shift as the cycles of meagre hopes and dashed expectations played themselves out.

The integration policies had always been justified prospectively: each measure was presented (rightly or wrongly) as a step towards full equality. But with the new approach yielding nothing but bitter harvests, its vast cost was increasingly justified in terms of the politics of atonement – a politics that, as well as placing itself above all criticism, lacked any natural limits and could only lead to ever-escalating demands.

The fact that the new approach was championed by a prosperous, largely urban, elite that benefited from the power, prestige and patronage emanating from the flood of interventions then gave that dynamic added momentum, compounding the damage.

All that was sure to make many Australians deeply uncomfortable. After all, if modern Australia has an ideal, it is that of a country that is “one and free”, in which all citizens have – to repeat Hasluck’s words – “the same rights, privileges and obligations”. Moreover, although there are undeniable flaws in our national history, Australians are typically proud of their country, admire its record in widening the circle of citizenship and of inclusion, and resent the relentless rubbishing of its achievements.

It should therefore have been obvious that the voice would raise serious concerns. Instead of learning from past mistakes, the proposal seeks to constitutionally entrench the separate representation that has failed whenever it has been tried and that experience and analysis suggest will continue to fail in the years ahead. And if the voice opens a door, it is not to equal political rights but to institutionalised racial division.

None of that is to recommend returning to the policies Hasluck adopted. Yet it is not just possible and permissible but vital to renew Hasluck’s overall vision, that so many Australians share, of political equality in a truly colourblind Australia – a goal that was blown off course by the abandonment, which the 1967 referendum facilitated, of the ideal of integration.

By placing that ideal back on the table, the referendum invites a mature discussion of where this country is heading. Unfortunately, rather than addressing that question, the Yes camp is resorting to cheap moralising whose purpose is not to convince but to silence.

Hiding behind a steam bath of emotions, it seems to believe moral blackmail can induce Australians into repeating the error of pursuing political equality by entrenching political inequality.

But it is worth remembering that Abraham Lincoln, in declaring that “A house divided against itself cannot stand”, warned that the nation’s utmost need was to understand “where we are and whither we are tending”. As we enter a period of high tension, Australians deserve better than another leap in the dark.

That the referendum on the voice will be among the most contentious in Australian history is beyond doubt. But for all of the harm it will cause, the proposed amendment at least forces into the open tensions that have simmered beneath the surface for far too long.