Indigenous voice: A chance to finish reform of original Constitution

The arguments for constitutional recognition have been widely canvassed since John Howard committed to it in the lead-up to the 2007 general election. The nature of Australia’s federation has thrown up legal complexities that have stymied a growing popular will to achieve meaningful constitutional recognition. These complexities have masked an overriding imperative to right a historical wrong that was entrenched in the 1901 legal document that federated the six British colonies into our single nation.

The founding fathers who negotiated and wrote the Constitution intentionally constructed a governmental framework to accelerate the disappearance of First Nation peoples. The national parliament was explicitly prohibited from making laws concerning First Nation peoples. The 1901 Constitution stipulated that the national government would not interfere with the brutal inhumane laws and practices of the old colonies, the new Australian states of the federated nation.

In 1967, more than 90 per cent of Australians voted to strike out those abhorrent provisions in the Constitution. That is what happens when political consensus matches the moral and political sentiment of the people. Yet while Australians voted overwhelmingly to expunge the offensive words that gave legal currency to conquest and colonisation, there were no words inserted that recognised and embraced the First Nations civilisations whose ownership and occupation stretch back tens of thousands of years.

Fifty-five years later, Australians have an opportunity to complete the constitutional reform process and to build an inclusive and respectful relationship between the Australian nation and its First Peoples. The Uluru Statement from the Heart, endorsed by First Nations representatives at Uluru in May 2017, is an eloquent and uplifting set of words that has been warmly embraced by mainstream Australia. Anthony Albanese has described the Uluru Statement as a generous reaching out to the nation by First Nations people.

He is right to describe it as generous. The concept of a constitutionally enshrined voice to advise the parliament and government was a creative compromise on the part of First Nations people to forge a pathway to recognition that serves two purposes: first, it responds to the wider Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community demands that constitutional recognition must have practical and meaningful application and, second, it can be supported by constitutional conservatives who worry that eradicating the 19th century concept of “race” from the Constitution, and replacing it with an inclusive provision that retains the commonwealth’s national responsibility for First Nations people, could be a de facto bill of rights.

As has been well canvassed, amending our Constitution is extremely difficult and any proposed change should be well scrutinised by Australians. This is perhaps why, inevitably, the most dominant and powerful Aboriginal voice to emerge since the Prime Minister committed his government to a referendum is that of Jacinta Nampijinpa Price. A powerful and credible voice who is clearly haunted by the failures of governments past and, as a result, has a huge suspicion of government present and into the future – the anger in the senator’s arguments is palpable. Price has thrown down the gauntlet to those, like me, who support the voice – explain why the voice is necessary in the lives of Aboriginal people and why non-Aboriginal Australians need not fear its existence. If you accept the obvious and well-known principle that we will achieve better policy outcomes if we include Aboriginal people in the decisions that impact them then that should lead you, inexorably, in support of a voice. Meeting Price’s demands for this evidence should not be a challenge for the likes of Linda Burney and Pat Dodson.

The difficulty will be meeting the public’s expectation of resolution – how do we conduct this debate in a way that does not leave our nation embittered and unable to move on to the real meat of this debate; that is, what do truth-telling and a treaty look like? It is here that the real reconciliation of our history will take place and it is here the public debate is likely to be more fraught – more confronting than anything the debate around a voice will throw up. The question is, can we, as a nation, in the way the modern political contest of ideas occurs, have this debate in a way that empowers us all?

There is clear evidence that popular sentiment to recognise First Nations people in the Constitution as a basis of developing a new and respectful relationship is ahead of the political class. Australians are ready for the conversation, and decision, on the voice.

Those of us who support constitutional change carry the higher burden of proof. We need to make our case. Those who support change cannot ignore, or denigrate, those who oppose or want more detail as ignorant racists any more than those who support change can be dismissed as elite wokes. The recent dispute between Price and Peter FitzSimons highlights this point; the argument has been around the tone of the debate, not the content of their discussion. The reality is that Aboriginal Australia, in its offer of Uluru, has accommodated all those issues the constitutional conservatives have demanded. It is indeed generous and gracious, as well as politically astute; those at Uluru have offered something that can be supported across Australia.

It is critical that political consensus is reached on the central question of First Nation constitutional recognition as occurred in 1967 – and this is where Peter Dutton finds himself in a position to have a significant impact on the way the debate is conducted. The Opposition Leader, more than most, is aware of the pragmatism displayed at Uluru and has himself regretted his position on the Apology. This is why I suspect he finds it difficult to navigate a path to clear opposition; the Aboriginal leadership has dealt with his concerns in Uluru. Even former PM Malcolm Turnbull, the person who did the most to derail consensus on a voice, has had the opportunity to reconsider the issue and is supportive.

Ideally, the central question should not be a matter of political combat. But the form of the proposed voice and issues surrounding treaty and truth telling should involve rigorous public discussion and debate. However, I fear the longer the conservative side of politics holds back on support for recognition, the potential for toxic politics will grow.

I for one am keen on a debate that leaves our nation empowered after taking a giant leap to right the wrongs of dispossession and assimilation. And I want my conservative colleagues onside in the fundamental question of whether our Constitution should accommodate a voice. That way the debate moves from what Aboriginal Australians deserve and on to how does the final consensus, the treaty, evolve and how does this embrace every single one of us.

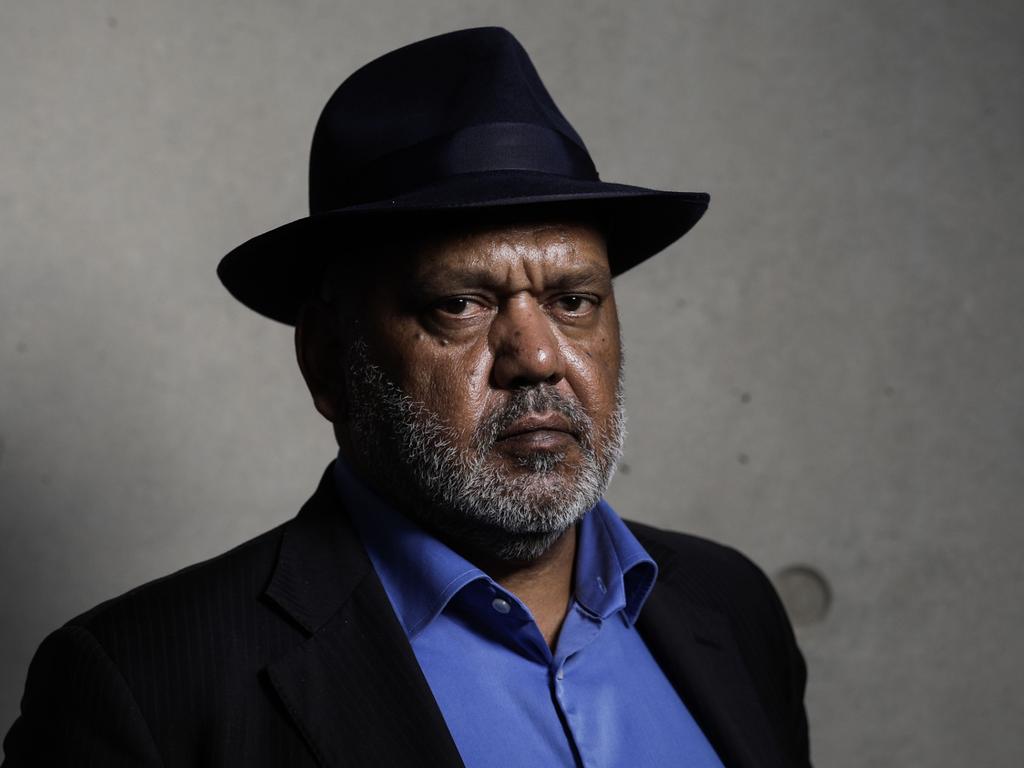

Ben Wyatt was the Labor member for Victoria Park in Perth from 2006-21. He was the West Australian treasurer from 2017-21. A lawyer, Wyatt is the first Indigenous person to sit on the boards of Rio Tinto and Woodside Energy.