The cashless debit card scheme was designed as part of a program to break the link between alcohol abuse and violence. The former Coalition government also wanted to ensure taxpayer funding for social welfare was spent on necessities such as food, rent and children instead of exacerbating addiction. The initial CDC program was co-designed with Aboriginal leaders and trialled in Ceduna, South Australia, where alcohol-fuelled violence was destroying town life.

Early analysis suggested CDC trials were producing sound results, including less alcohol consumption and related violence. However, critics pointed to flaws in the evaluation methods to suggest the findings were unreliable. Unfortunately, they were substantially right.

To properly evaluate the direct impact of social policy is very difficult. The gold standard of impact evaluation requires more investment and resources than most organisations and governments are willing to provide. For example, individual tracking is involved and that can only reasonably be achieved with the consent of participants. Achieving such consent means building relationships of trust with often vulnerable members of our community.

Many social programs introduced by governments fall victim to the electoral cycle. In the case of the CDC, the problem was compounded by revolving-door Liberal leadership and consequent ministerial reshuffles. For example, the Auditor-General report on the CDC trial performance notes that the evaluation strategy was approved by the assistant minister for social services on February 17, 2016, a day before Alan Tudge left the role to become minister for human services under prime minister Malcolm Turnbull. Labor and the Greens have compounded the problem by trashing a program with great potential and some useful data instead of reforming it to improve delivery and evaluation.

Labor has provided no robust evaluative evidence to support eliminating the CDC program in its entirety. It uses selective findings taken out of context and anecdotes to support angry rhetoric about it constituting racism or violence.

At least one recipient has been quoted repeatedly by Labor and the Greens to support their case against the cashless debit card. In a 2019 interview with ABC-TV’s 7.30 program, Kerryn Griffis complained the card made her feel like a lesser person: “What have I ever done for the government to treat me this way?” In 2020, Greens senator Rachel Siewert quoted Griffis to argue against the CDC in the Senate, saying: “These are extraordinary words: ‘In the government’s eyes, I’m a lesser person’. This government is treating people as if they are worth less.” Labor MP Justine Elliot justified her government rolling back the CDC by using anecdotes from people allegedly victimised by the scheme. She quoted Griffis, “a mother of five” from Bundaberg, who described the debit card as “a nightmare” and “traumatic”. She celebrated the end of “being restricted by which bill I will and won’t pay”. Greens senator Janet Rice referred to Griffis on Twitter to argue the “CDC & BasicsCard must end”.

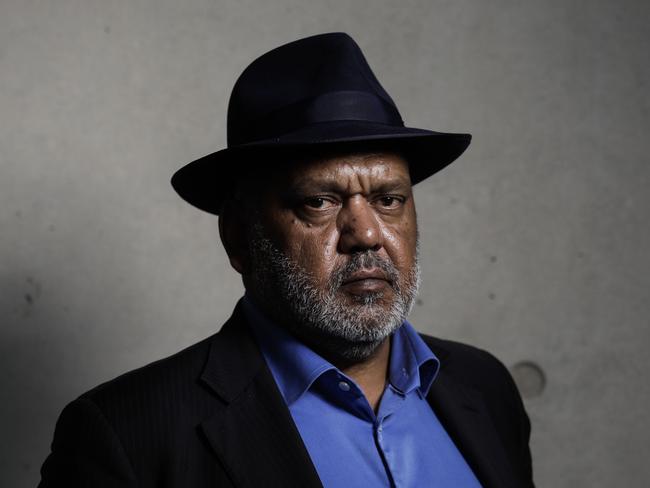

By contrast, respected Indigenous leaders such as Cape York Institute founder Noel Pearson would like the mutual obligation approach embodied by income management schemes to remain a feature of anti-violence work in Indigenous communities. Pearson told a public hearing his team introduced an income management program in 1999 to tackle Indigenous disadvantage. It applied to both welfare recipients and wage earners as a protection against financial predators he identifies as grog sellers and alcohol outlets, gambling venues, and merchants who sell second-hand goods at inflated prices. And there are implicit cultural beliefs that could make the kind of voluntary income management Labor wants unworkable on the ground. Pearson describes a practice called “demand sharing”, an expectation that an Indigenous person with cash should give it to relatives who demand it.

Country Liberal Party senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price says scrapping the CDC scheme would result in increased alcohol and drug-fuelled abuse of women and children. In a 2020 article for The Spectator, she described the practice of “humbugging”, which is where people harass family members for cash by claiming they need it for essentials while refusing offers of food.

Cashless income means Indigenous people could have a better chance at safeguarding money from addicts who would deprive families of food and other basic necessities to satisfy their addiction. In the long run, if enough communities joined the program, addicts would have far less access to their drug of choice and alcohol-fuelled violence would diminish. Such an outcome would benefit Indigenous Australians and the broader community.

Labor and the Greens assert that abolishing the CDC will be beneficial and most Indigenous people agree with them. However, as The Australian’s Cameron Stewart reported, the silence of supporters has been engineered. Indigenous elders co-designed the CDC program in Ceduna and told Stewart they had received threats for speaking in support of it. Residents of Laverton, however, have asked for extra police support in anticipation of surging violence after the CDC scheme is abolished and alcohol-fuelled rage returns. And the ABC has reported that in the East Kimberley region of WA, Indigenous people are expressing concern that abolishing the scheme will result in more alcoholism and violence.

The former Coalition government bears significant responsibility for the problems with the CDC scheme. However, Labor and the Greens have politicised the issue by claiming income management is paternalistic and violates the principle of self-determination. They might consider that nothing quite dims the hope of self-determination like a fist in the face. Anyone or anything that stands between an addict and his victim is a welcome interruption. If governments have to intervene, so be it.

You do not have to be Indigenous to know alcohol abuse makes sane men mad and children weep. Alcohol-fuelled harm ranges from crime against property to lethal family violence and the devastating loss of human potential in foetal alcohol syndrome. Despite the evidence of harm, Labor has worked with the Greens and key independents to wind back welfare reforms aimed at preventing alcohol abuse in vulnerable communities.