This does not mean everybody is safe from cancellation, or that the identity-politics left has lost its power. But the momentum behind many social media campaigns to get people fired or excommunicated from polite society does appear to be subsiding.

Data is hard to come by in the Australian context, but sociologist Musa Al-Gharbi has compiled evidence from the US that shows many of the trends associated with the “Great Awokening”, as he calls it, peaked in 2021.

One researcher Al-Gharbi cites is New Zealand data scientist David Rozado, who has analysed trends in popular US newspapers. In recent analyses, Rozado has found the use of the words “racist” and “racism” steadily increased between 2011 and 2021, but over the past two years has been in decline.

Words associated with feminism and climate change doomism were also found to have increased sharply from 2011 to 2021, but now seem to be diminishing as well.

Notwithstanding these positive trends, we are still nowhere near where we were before 2011. People can still get into trouble for ideological heresies and those working in politically homogenous environments – such as academia – remain the most vulnerable. Holly Lawford-Smith is a good example of an Australian academic who has been a target of cancel culture simply for defending the reality of biological sex.

Yet academia is not reflective of the culture at large. It is insulated from market forces, and not subject to the creative destruction the free market naturally brings. And in the realm of the free market, consumers are having their say.

Last year, Disney grappled with losses of $300m, attributed to movie releases that were panned for being too “woke”. Two films featuring LGBTQ+ relationships flopped and Elemental, starring a non-binary character, marked Pixar’s weakest opening weekend in nearly three decades.

Celebrities who were cancelled during the #MeToo era have returned to the limelight and are enjoying successful post-cancellation careers. Louis CK sold out Madison Square Garden earlier this year, and runs a thriving independent business selling his comedy specials direct to consumers.

And The New York Times – an institution that has in the past fired employees for running afoul of progressive orthodoxy – suddenly found some fortitude this year. When an LGBTQ+ lobby group and disgruntled employees published an open letter demanding the paper apologise and sack people over their coverage of trans issues, the Times put out a statement saying it would do no such thing, and that it stood by its editors.

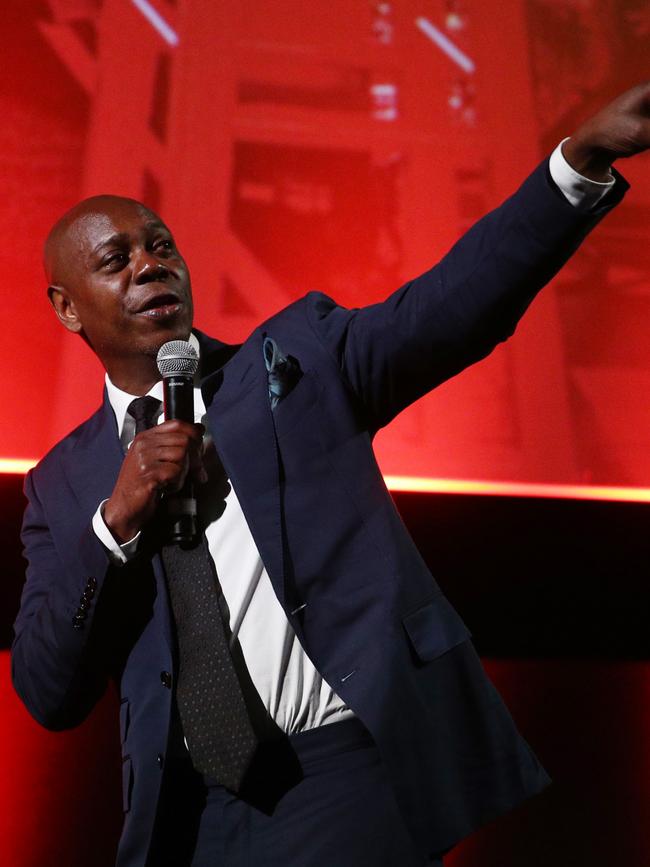

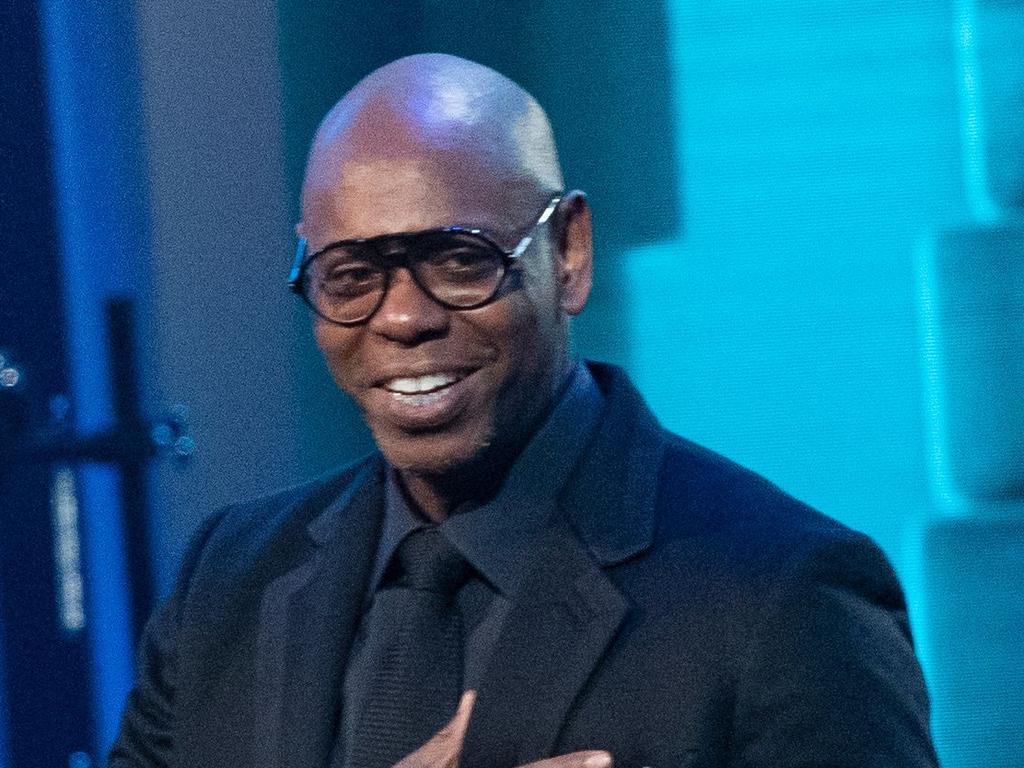

In a similar vein, when workers at Netflix demanded Dave Chappelle be dropped over his jokes regarding trans people, the streaming company’s bosses issued a memo effectively saying “if you don’t like it – leave”. When disgruntled employees didn’t take up the opportunity to resign, Netflix fired them anyway.

And in the financial world, Larry Fink of BlackRock, a leading investment firm, has distanced himself from the term “ESG”, which refers to environmental, social and governance investing. Fink mentioned the term’s overt politicisation as a primary reason, though a $4bn financial setback earlier in the year due to backlash surrounding ESG may have also played a role.

Of course, the embers of cancel culture are still with us, and modern “woke” trends are still smouldering. But the intensity of these movements are not what they used to be, and fewer individuals are facing backlash for criticising them.

One reason for this may be that the recent advocacy for trans rights has been alienating to many otherwise sympathetic women. Inner-city yoga mums who were happy to signal their support for #MeToo and #BLM, do not necessarily like being called “birthing persons” who “chest feed”.

Another factor is the shift in economic conditions. Rising interest rates and inflation mean many companies must shed employees. Those who instigate petitions against their colleagues and who otherwise foment dissent are, of course, the easiest to let go. And in 2023, many institutional leaders are not as spooked by social media mobbings compared to just a few years ago.

This subtle change in behaviour from institutional leaders, such as those at Netflix and The New York Times, suggests we are becoming more accustomed to our modern communications technologies.

Although cancel culture emerged out of social media’s capacity to mobilise collective reactions, society at large is now more resilient to the illogical aspects of such reactions.

Instead of participating in or panicking about outbreaks of mass hysteria, we are collectively learning how to navigate and move past them.

And perhaps, finally, cancel culture is just no longer cool. Al-Gharbi notes a “vibe shift” among millennials and Gen Z. Many young people are beginning to see the culture wars as tedious and unfulfilling, and the need to constantly advertise their “right-thinking” as exhausting.

And, as al-Gharbi explains, a growing number of young people just want to relax and have fun rather than “having to be so neurotic, guarded and paranoid”.

Claire Lehmann is founding editor of online magazine Quillette.

A trend to be optimistic about is the fact that cancel culture appears to be dying down.