As Holly Lawford-Smith’s experiences show, feminism is not safe on our campuses

Academic Holly Lawford-Smith has had a security guard stationed outside her tutorial room. These days, feminism is not so welcome on campus.

Honi Soit records that in June 1973 a small group of feminists and leftist activists kicked off a historic battle to offer students the first women’s studies course at the University of Sydney – and only the second in the country. Two PhD students, Jean Curthoys and Liz Jacka, wanted to teach a course called Philosophical Aspects of Feminist Thought.

The university professorial board’s rejection of the course led to a month-long strike by staff and students, supported by the Builders Labourers Federation and other unions. The Philosophy Strike, as it came to be called, was the precursor to the arrival of intellectual feminism on campus.

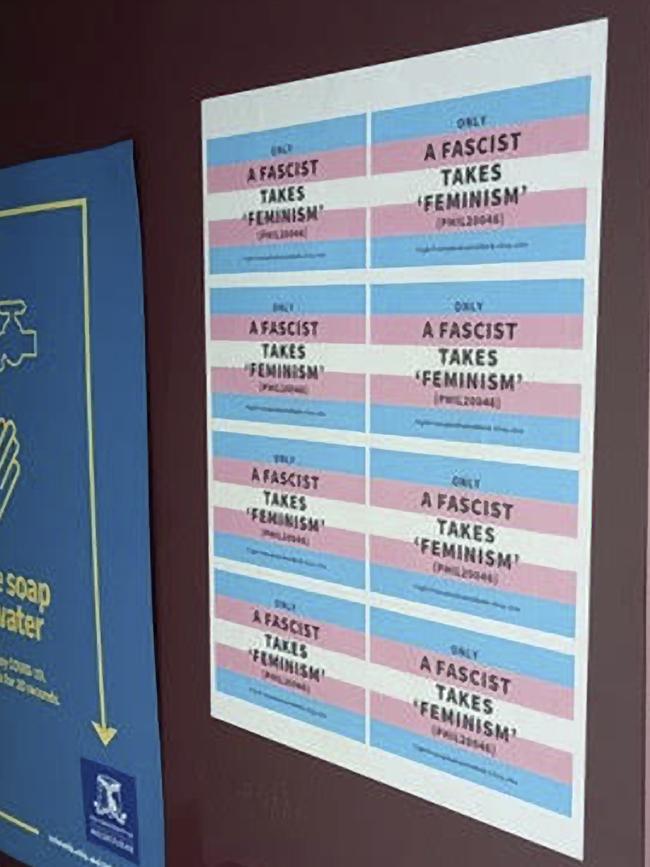

Fifty years later, philosopher and feminist academic Holly Lawford-Smith has had a security guard stationed outside her tutorial room at the University of Melbourne to protect students from disruption during her feminism course. At times the guard also has escorted Lawford-Smith as she walks the short distance from the Old Arts building, across a path called the Professors Walk, back to her office in the Arts West building. Feminism is not so welcome these days on campus.

What has gone wrong? Before women had rights, imparting feminist thoughts may have been dangerous. But now? In 2023? This is nuts. Ferret around the wondrous English language all you want. There is no other word. Has feminist philosophy so lost its way that it no longer deserves a place on campus? Or is there something seriously wrong with those forces that have led to a security guard being posted outside a feminism tutorial room?

To answer these questions, we should start with what Lawford-Smith teaches. Her intensive course of 24 online lectures and 12 in-person tutorials for PHIL20046: Feminism covers topics one would expect: “Are women oppressed?” and “Patriarchy”, “The sex industry” and “Beauty norms and women’s revolution”. Given the security guard stationed outside Lawford-Smith’s tute room, maybe the trouble stems from lectures 21 and 22 on “sex/gender identity”.

Yet it would be remiss of an associate professor in political philosophy not to discuss in a feminism course the difference between sex – a woman’s biology – on the one hand, and gender, where a man self-identifies as a woman. And it would be entirely ridiculous to expect all academics to agree that gender identity is a sufficient reason to up-end feminist teaching about issues confronting women that are rooted in women’s biology.

In an interview with Inquirer this week, Lawford-Smith describes the first time she faced intense hostility for believing that a woman’s biology is central to the teaching of feminist philosophy.

In March 2019, the philosopher was interviewed for cultish literary and philosophy magazine 3:AM. After discussing mostly ethical and collective responsibilities about climate issues, she was asked about the trans issue and her gender-critical beliefs.

“It really has become toxic,” Lawford-Smith told interviewer Richard Marshall. “I’ve been surprised by the levels of vitriol that have been directed at me and other radical and gender-critical feminists within the profession. My stance is that a person can’t change sex (not even with sex reassignment surgery), that ‘gender identity’ has no bearing on sex, and that with very few exceptions gender identity should have no bearing on a person’s sex-based rights.”

“Some trans women inside the magazine complained to the editor to get the piece taken down,” Lawford-Smith tells Inquirer. Her interview was pulled. Marshall quit the magazine in protest against the censorship.

It started escalating from there. There were threats of protests and attempts to deplatform Lawford-Smith and another gender-critical academic at the University of Reading in Britain a few months later. “But they (university administrators) stood their ground and let the public event go ahead rather than give in to the protesters.”

Lawford-Smith mentions the Australian Association of Philosophy conference in Sydney in July 2019. Her conference abstract about women-only spaces led student organisations and other groups to organise protests. “I walked into this big conference, maybe 300 or 500 people go, and there was security everywhere and I was thinking, ‘Oh, did something happen?’ And then I realised that they were there for me,” Lawford-Smith says, matter of factly.

“I just remember it so vividly. My heart was racing. I felt like, ‘Oh god, everyone must be staring at me. I’ve caused all this fuss.’ ”

Though the online threats were extreme, protests didn’t eventuate that day. In June 2019, Lawford-Smith’s Twitter account was permanently suspended – it was pre-Elon Musk.

In September 2019, student activists tried to cancel her talk called Deplatforming is a Feminist Issue at RMIT.

“I’m sure the irony was lost on them,” she writes on her online Censorship timeline.

That the philosopher can fill five pages about censorship attempts against her is evidence of the level of abuse and hatred she has endured. “It felt really intense being a person who was hated that much by a small sector of society,” she says.

After a few more extreme online hate fests against her failed to translate into physical protests, Lawford-Smith says she realised that the numbers were small.

“That just took some experience to learn that the numbers (of trans activists) are puny,” she says.

I come back to why is there a security guard being posted outside a Melbourne Uni tute room to protect students who want to learn about Lawford-Smith’s feminism? The university, she says, has overreacted on many fronts, bestowing more power on a small group of trans extremists than they deserve.

Lawford-Smith is known as a “radical” feminist because her focus is on women and their biology. Radical? How times change. Her new book, Sex Matters: Essays in Gender-Critical Philosophy, was not an easy project, either.

Publication was halted by Oxford University Press last year. Matters were resolved and the book is out this week. Originally classified as a book for a general retail audience, it has been reclassified by OUP as an academic book.

Nothing is easy if you believe feminism is for women. Does that make Lawford-Smith a TERF? The term trans-exclusionary radical feminist is thrown around a lot these days.

“TERF is a slur. I’m trans women exclusionary from feminism,” Lawford-Smith explains. Not from society, note. From feminism. “It is indispensable to our form of feminism to have the concept of femaleness because women are the people to whom subordination, marginalisation has been done over centuries.”

Can’t feminism include trans women?

“It’s hard to see how it would be coherent. You could say we have this constituency of female people who, by their biology, have been mistreated over the centuries. Oh. And there are also trans women.”

But she says these two groups – biological women and trans women – “have nothing in common; there’s not a shared constituency. There’s not much at all of an overlap between the groups.”

Lawford-Smith says including trans issues in feminism has changed the focus, away from issues facing women and feminist politics to those facing trans women who claim to be the most marginalised.

Is the trans movement trying to take over feminist politics?

“Absolutely. That’s my impression,” she says. “Somehow – and I can’t fully account for the hostility and aggression of it – but somehow you’re not allowed to just talk about women any more.

“There’s a sense now that feminism has kind of accomplished its goals and there isn’t really a problem any more. So why would you want to talk about women when you could be talking about trans people? The gender studies approach has assumed cultural dominance. That’s the big project that cares about everyone and everything. And it’s wrong to take the women’s studies approach, which is the approach that I’m taking.”

If issues facing women and trans women differ historically and intellectually, why not a separate university course for students who want to explore trans issues?

“I ask myself that question all the time.” Instead, “feminism is being devalued”, Lawford-Smith says.

This is not just an intellectual debate. It’s about women-only spaces, and sport, and our language where a woman’s essential biology is being erased. Tampons are for “people who menstruate”, breastfeeding has become “chest-feeding”, untethered from a woman’s biology, and new laws allow gender self-identification.

In short, modernity’s diversity- and-inclusion project is excluding large parts of what it means to be a woman, and necessarily undermining women’s rights, to accommodate a tiny group of biological men who identify, in gender terms, as women.

The irony of an inclusion movement excluding women and their biology is not lost on Lawford-Smith, let alone millions of people off-campus who wonder whether trans extremism has peaked.

Certainly, in some sports there is a reckoning with reality about male physiology up-ending an equal playing field. Business is not immune either, with the manufacturer of Bud Light beer in the US learning that tagging on to the trans issues was a dumb idea for business. Former Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon learned the hard way about overreaching on gender self-identification laws and what that meant for female prisons.

Meanwhile, in Britain last week, tax expert and feminist campaigner Maya Forstater was awarded more than £100,000 ($190,600) after she was discriminated against, losing her work contract, because she expressed her view that “male people are not women”.

Though there are signs of trans extremism causing the first major chink in the woke movement’s armour, academia is proving to be more obscurant.

Lawford-Smith says it drives her crazy that the university has had ample opportunity to see that this is not actually a sizeable threat yet they keep pandering. She points to policies that have turned university bathrooms into shared spaces.

“The policy has invited (into female-only bathrooms) any male who decides that he would prefer to use them,” she says. “This tiny proportion of trans students is prioritised over the interests that any female students of any religion or culture might have to having single-sex bathrooms.”

The university’s new LGBTQIA+ Inclusion Action Plan allows students to lodge grievances against course curriculum, putting Lawford-Smith’s course in the direct line of fire from trans activists. She notes that none of her students has complained about her course; complaints have come from students who have not done her course. But this could change, she says, if trans activists take her course simply to try to shut it down.

More broadly, the philosopher feminist is concerned that policies about the “safety and wellbeing” of students could be weaponised to stop important debates.

Whereas once it was about hurt feelings, the new battleground is over “wellbeing”. It’s easy to see how this equally slippery term could be exploited by trans activists to censor a feminism course that focuses on women and their biology.

Lawford-Smith, who has lodged a complaint against her employer for not protecting her from spurious attacks, is disappointed at the lack of support.

“I don’t think the (university) leadership have shown that they understand that you cannot serve two masters,” she says. “They constantly make statements that they’re trying to balance academic freedom against diversity and inclusion. I just think that’s not true.

“These two objectives pull in really different directions.”

The contemporary corporate diversity and inclusion mantra on campus of creating a safe place where everyone’s comfortable, where everyone feels celebrated, is not consistent with rigorously challenging orthodoxies, she says.

Some discussions that prise open our minds to new ideas may be uncomfortable and potentially even distressing.

“A lot of students today just uncritically swallow gender identity ideology and don’t see any kind of conflict with feminism. I can perfectly imagine going into a first-year subject and trying to teach something slightly critical about reifying gender as identity and having most of the class against me and think I’m transphobic.

“We want to be able to challenge orthodoxies. That’s the really important thing. If there’s something where that’s just what we progressives do now, you want to be able to challenge that and make sure it’s a view held for good reason.

“How do you gain new knowledge? How do you overthrow old paradigms? How do you really pursue the truth at all costs and also keep everyone really comfortable?”

We have no law of physics to help a cultural pendulum settle somewhere more sensible. Only a healthy marketplace of ideas can do that. And that requires people such as Lawford-Smith to keep teaching what is now deemed “radical” feminism.

But back to that security guard. Is there room for feminism on campus? The philosopher pauses. She’s not sure.

“It seems nuts if the answer is no, right? It’s absolutely nuts.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout