It was the precursor to blocking the Franklin Dam and the first tentative steps into politics and the law. Today, green activism in Australia is a quarter-billion-dollar business that employs hundreds of people. Research published this week by the Menzies Research Centre shows the combined revenue of the top 25 green advocacy groups was $275m last year. The revenue has more than doubled from $113m in 2015. The number of staff on their books has increased from 374 to 880.

Ironically, the report finds that the green activist industry is growing faster than the primary industries and resource sectors it targets. Its goal is not to create wealth but to destroy it. It forms part of the NGO-corporate-industrial complex that has discovered how to profit from the war on carbon, aided and abetted by the government through subsidies and regulation.

The environmental juggernaut of today bears little comparison with the green movement that began in Tasmania almost half a century ago. Its focus has changed from conservation to the ideology of climate change. The movement has become remote and insensitive to the natural environment and developed a narrow-minded obsession with carbon emissions from coal and gas combustion.

The big environmental groups are wholly committed to renewable energy and dogmatically opposed to nuclear power. To the extent that we’re able to trace the source of their funding, much of it flows from investors in the renewables sector whose portfolios would be instantly devalued by the entry of nuclear power.

Activist organisations have become so dependent on green corporatism that they are willing to ignore the destruction of broad acres of natural vegetation for the construction of wind turbines, industrial solar plants, energy storage infrastructure and associated transmission lines.

Climate warriors are more likely to be found in the courts these days rather than tied to the front of a bulldozer in the tropical forests of the Upper Burdekin in far north Queensland. Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek’s approval of the Upper Burdekin/Gawara Baya wind development last month came despite a damning report that warned of “unavoidable significant impacts” on the endangered Sharman’s rock wallaby, the koala, the greater glider, the red goshawk and the masked owl.

Nowadays, lawyers perform much of the heavy lifting for climate activism. The MRC’s research found that Australia is the second-largest forum for environmental lawfare after the US. There are more climate lawsuits per capita in Australia than anywhere else in the world, thanks to a rich array of resource sector targets and an obliging legal system.

The bar for launching court actions in Australia is low for those with funds. Every dollar spent by legal activists is a drain on the profits of businesses forced to defend themselves against adventurous and vexatious claims. The biggest cost to the resource sector is not legal fees, punishing as they are. It is the mounting cost of interest on borrowed money that sits idle while the legal process drags on.

The MRC calculates that in past two years $17.48bn in industrial output has been frozen by legal action. Whether investors will see a return on their capital is at the mercy of the courts. The damage is compounded by the damage to the broader economy.

The MRC calculates 29,784 Australian jobs are at risk in cases before the courts. The loss of taxes and mining royalties will make it harder to fund roads, schools and hospitals and support our health and education systems.

The fiscal impact alone would prompt a clear-thinking government to step in and clean up this mess. The Albanese government, however, is anything but hard-headed about anything related to the environment. It refuses to countenance any reform that might give the Greens party an edge in quinoa-chomping enclaves such as the seat of Grayndler, the fate of which is of more than passing interest to our PM.

It gets worse. In an act of fiscal self-harm, the government is subsidising legal activism that eats into the profits it likes to milk. The 2022 budget included $10m in funding for the Environmental Defenders Office and Environmental Justice Australia, the two bodies responsible for most environmental lawfare in Australia.

In 2015, the EDO had 14 staff and a $3m budget. By 2023, it had grown to a team of 105 staff and a budget of $13.3m. It measures success with a perverse set of metrics. Its 2022 annual report boasts of providing 11,587 legal hours and spending 134 days in court.

In January, the EDO’s tactics were heavily criticised by Federal Court Justice Natalie Charlesworth, who reversed an order preventing Santos from building a pipeline allowing the $5.8bn development of the offshore Barossa gas field. She rejected assertions by three Tiwi Islanders that the pipeline posed a risk to intangible underwater heritage, including Crocodile Man song lines and an area of significance for the rainbow serpent Ampiji, and was not “broadly representative” of the beliefs of Tiwi people who would be affected by the pipeline.

Charlesworth found the EDO had engaged in dishonest “coaching” tactics and the misrepresentation of local Indigenous knowledge. Charlesworth dismissed evidence from the EDO’s expert witness about potential impacts on underwater archaeological sites, finding there was a “negligible chance” of a significant impact on tangible cultural heritage. Charlesworth found a cultural mapping exercise undertaken by an expert witness for the applicants and “the related opinions expressed about it are so lacking in integrity that no weight can be placed on them”.

“I am satisfied that this aspect of the case does indeed involve ‘confection’ or ‘construction’, at least in part, and that it cannot be an adapted account of the kind discussed by the anthropologists,” the judgment states.

Yet despite the loss of the case, the activists are winning. The global demand for liquid natural gas has never been higher, and is forecast to continue to rise until the 2040s. Yet oil and gas exploration activities in Australia have been falling significantly over the past two decades. The number of new offshore wells has fallen from over 50 in 2010 wells to just three in 2023. When your aim is to frustrate and delay, there is no such thing as a wasted day in court.

Nick Cater is a senior fellow at the Menzies Research Centre and a visiting fellow at the Danube Institute.

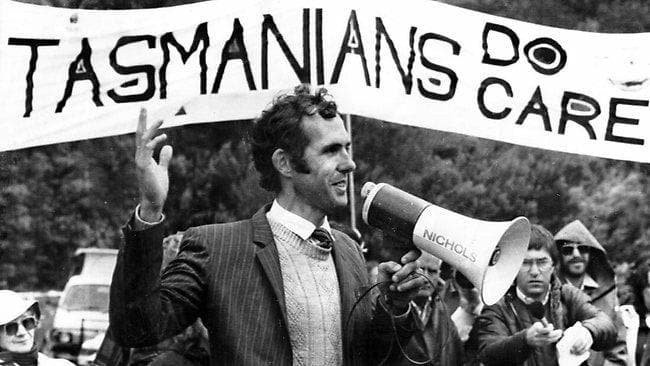

The anti-industry industry has come a long way from its humble origins in the late 1970s, when Bob Brown went to his local St Vincent de Paul and bought himself a suit. The transition from a gaggle of amateur nature lovers to a professional organisation with salaried staff was a giant evolutionary leap for the environmental movement.