Get back to basics in schools and skills to lift performance

Yet it’s arguably the most important and personal one as it penetrates to the heart of what Australia must achieve for future generations to prosper: maximise our brain power and help our people adapt to the rapidly changing world of work.

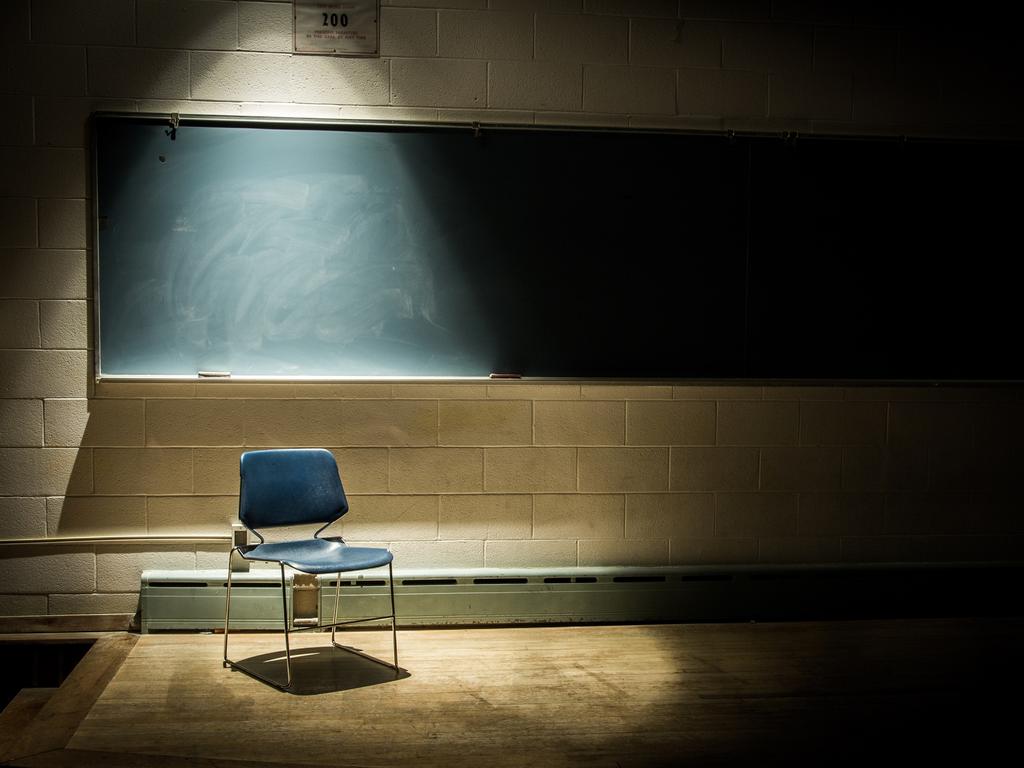

The commissioners correctly identify the baseline for success: if we can get better outcomes in the classroom, through proven methods of teaching the basics, the nation will be on a smoother path to the productivity frontier

We have abundant land and natural resources and, given our retirement savings pool and openness to foreign investment, ready access to capital.

But we’re not making the most of our people, or for that matter, using the migration system in a way to cash in on the world’s footloose and talented workers who want to commit to a life here.

Our workplace relations system and occupational licensing err on the side of rigidity and bureaucracy, rather than being sensible and adaptable institutions.

There will be pushback on some proposals to free up who can work where and how, as well as from universities about recognising credits for learning at other institutions, especially those down the educational food chain.

As the PC report makes clear, we need to get back to foundational skills in literacy and numeracy, with teachers using explicit methods of instruction that are backed by the evidence.

The evidence is in and suggests the fads of student-centred learning have led to a cratering of performance compared with other rich nations, never mind the extra funds poured into education these past two decades.

Some school systems have woken up to this, as have parts of the education architecture, primed to use data rather than vibes. But getting all systems on the same page will take time – the longer it takes, the more we risk failing those who need old-school methods the most, such as disadvantaged students in remote areas.

It’s trite to write, but it begins with classroom teachers: we expect too much from most and too little from some.

School days are longer, swamped by form-filling, discipline issues and after-sales service for high-fee customers and ordinary taxpayers.

Teachers need to be liberated from the burden of well-meaning compliance and given more time to develop their lessons, update their skills and put the bulk of their toil in classrooms.

While investing in a single national platform for all teachers to access lesson planning materials is an obvious way to help the time-poor, the real magic will come from how these materials are adapted for local conditions by conscientious mentors.

We are in the early stages of dealing with the promise and perils of AI; it’s a must-have tool in a worker’s kit bag for the times and yet it can also be a slippery path to deskilling, especially on core skills such as literacy and analysis.

Successful countries have put “reskilling” at the centre of worker training. But lifelong learning works only if you have a bedrock of numeracy and literacy to begin with.

It’s important to note the PC did not try to reinvent the skills and education systems, rather to opt for some measures that can be done with minimal regret or sector warfare.

Much change is already in train in the workplace and educational systems and the PC advises governments to keep gathering the data, ask hard questions about resource allocation and pay attention to how all the parts fit together.

Too many kids are leaving school without the basics and are denied from achieving their potential.

An ageing nation that has to earn its way in a hostile and volatile global economy, with proportionally fewer workers, must skill up or trade down to a lower standard of living.

The Productivity Commission’s advice on building a skilled and adaptable workforce will probably attract less attention than the other four editions on the pillars of prosperity.