NAPLAN 2024: Return to old-school teaching methods sends students’ results through roof

An old-school teaching method known as explicit instruction has lifted student performance in this year’s NAPLAN tests of literacy and numeracy | SEE THE LIST of schools making a difference

A Catholic school cluster has shot to success in this year’s NAPLAN results, after abandoning failed teaching fads through the nation’s biggest experiment in the science of learning.

A return to the old-school teaching style of “direct instruction’’ has delivered academic dividends for 23,000 students at 56 Catholic schools in the ACT and Goulburn, based on the NAPLAN) results for 9629 schools to be made public on Wednesday.

The Catholic schools make up 13 of the 20 schools flagged by the Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority as “making a difference’’ in the ACT.

Just a quarter of schools in the ACT are Catholic, yet they make up two-thirds of ACARA’s list of schools that out-performed others with a similar background of parental occupation and education.

For years the Catholic schools had underperformed – until the Archdiocese of Canberra and Goulburn embraced direct instruction, also known as “explicit teaching’’, through the Catalyst project in 2020.

Four years later, the schools have caught up to deliver their best-ever NAPLAN results.

“We’ve seen dramatic improvement,’’ Ross Fox, the director of Catholic Education for the Archdiocese of Canberra and Goulburn, said on Tuesday.

“We’re seeing students who fell behind making substantial progress to catch up because of our intervention programs, and we’re seeing time saved for teachers.

“The incidence of disruptive behaviours has reduced, in part because our students are more engaged in their learning.’’

Mr Fox said teachers were saving five hours a week in lesson preparation because the Catalyst program provides high-quality lesson plans and “commonsense curriculum materials” used in all classrooms.

The Catalyst program is based on the scientific concept of “cognitive load theory’’, to ensure new information is embedded in students’ long-term memory. Students are not overwhelmed with new information, and are given time to practise and repeat concepts until they’ve mastered them.

Teachers direct and closely monitor students’ learning – a reversal of the failed fad of “student-directed learning’’ that expected students to “lead their own learning journey’’.

Catalyst was designed by Knowledge Society, which is also working on explicit instruction techniques with 26 Catholic schools in the Geelong region, 51 schools in the Sandhurst Diocese in Victoria, and 20 public schools in Western Australia.

“There is a science to how humans learn and it is about being very specific about what’s being learnt in each lesson, ensuring the lessons are fast-paced and highly interactive, with lots of checks with the kids for understanding,’’ Knowledge Society chief executive Elena Douglas said.

“Education is like medicine; there are practices that are proven and evidence-based, and practices that are wishful thinking.’’

The Catalyst experiment has been transformational for Mr Fox, who believes that education has for far too long “had a real bias towards novelty’’.

“Unfortunately, we often chase what might seem new, rather than what’s most effective for learning and what’s most sustainable for the teacher,’’ he said.

“Now the teachers across our 1000 classrooms have an understanding of the science of learning.’’

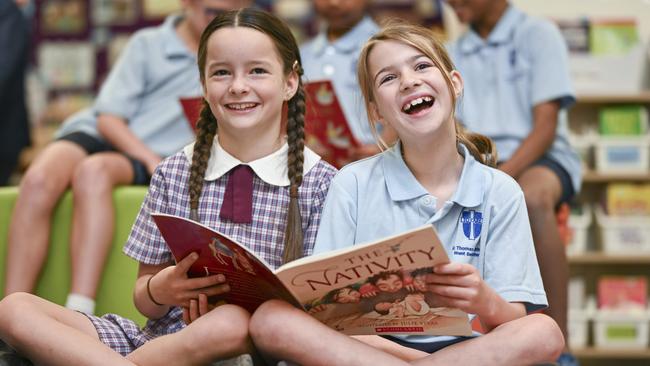

The Catalyst project has improved student learning at St Thomas Aquinas School in Canberra, where students had performed below-par in reading in year 3 and year 5 in NAPLAN tests three years ago.

Principal Tim Cleary is keen to spread the swift success to other schools. “It works, you can see the results – and the kids love it,’’ he said. “Evidence shows that students learn best when they are given explicit instruction accompanied by lots of practice and feedback.

“They’re not sitting in groups anymore – they’re sitting in rows, old-school.

“We’ve gone back to what happened when I was in kindergarten in 1970 – I still remember the colour-coded phonics cards.’’

Explicit instruction has also produced top results at Ipswich Grammar School, where students in every year level out-performed their peers at similar schools this year across every domain of reading, writing, spelling, grammar and numeracy.

The primary school boys find lessons fun as they chant their times tables and sound out letter combinations in phonics-based reading lessons.

Before the school became one of the first to embrace direct instruction in 2016, it ranked 128th among Queensland primary schools. Now it sits third.

Another high-achieving school that has defied the odds for its low socio-economic demographic is Canley Vale High School in Sydney’s west, which outperformed similar schools across every domain in this year’s NAPLAN results.

Principal Effie Niarchos said the school had introduced extra standalone literacy lessons – two a week for students in years 7 and 9, and three for year 8 students.

More than half the school’s students live in the poorest 25 per cent of families, and 97 per cent live in predominantly Vietnamese households where English is a second language.

Ms Niarchos said the literacy lessons were “very structured, very explicit’’, but tailored to suit different classes and individual students. She credits migrant parents for encouraging their kids to do well at school.

“The parents are aspirational and they really value education,’’ she said. “Those strong values are associated with coming to a new country and making sacrifices, and education being the key to unlocking a brighter future.

“Knowing that our parents are supporting us through that very strong message at home really helps to support a sustained focus on learning in our school.’’

Another successful school with high concentrations of poverty and newly arrived migrants is Fairfield West Public School in Sydney, where one in three students is a refugee.

The school uses explicit instruction methods and has performed above the average for similarly disadvantaged schools across every domain this year.

Free breakfasts and help to buy uniforms or lunch are used to lure students to the school.

An Arabic-speaking administrative assistant liaises with families, checking up on absent students and even helping families to book medical appointments.

Principal Genelle Goldfinch said her priority was to get children attending classes. “Many of our students come from traumatised backgrounds,’’ she said.

“We have food here, and will call in and check at home if everything’s OK when a student’s away, and that’s significantly helped with attendance.

“If they’re not at school, we can’t teach them.’’

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout