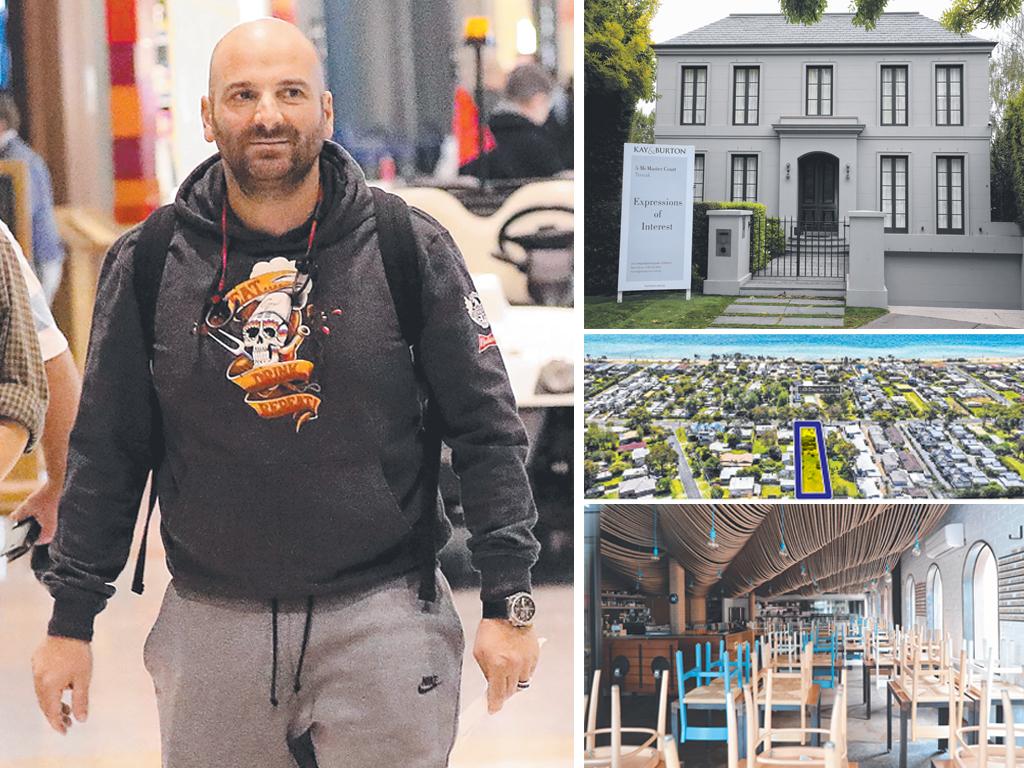

George Calombaris gets done like a dinner

In between, there have been pointed remarks about how other miscreants — for example, the ABC — have not been subject to the indignation that a commercial operator has faced for not having paid his staff in accordance with the labyrinthine government-specified rates.

There are three points that better describe what has taken place.

First, other than in the context of the highly regulated labour arrangements that cover the Australian hospitality industry, there was no fraud involved. The employees agreed on a package of wages, hours and other responsibilities; they were for the most part seasoned workers within the industry, were adult and able to decide for themselves what pay and work trade-offs suited them. Hospitality is an industry with highly intense competition for staff and for jobs, and one where the employees are acutely aware of different opportunities. They are not gullible fools in need of protection from a monopoly hirer.

Second, Calombaris is the trendsetter and supplier of excellence in the hospitality industry and has leveraged this into a media reputation. People looking to gain good experience at the pinnacle would seek to work for him.

Many of the farsighted would agree to do so at a discount, rather like many of those looking for a career in journalism who pay a premium to get credentialed from US universities such as Columbia or Northwestern rather than settle for qualifications from Swinburne. Similarly, aspiring high-flyers in the advertising industry gravitate towards New York’s Madison Avenue firms, where they typically earn less than in other agencies, recognising the work experience helps their future earning capacity. And we see the phenomenon of tech start-up firms where young people work long hours and investors make huge outlays in both cases for very little recompense, hoping to benefit if the technology is successful.

Third, Australia is almost unique in having a wage-setting arrangement by government entailing high minimum wages that vary within multiple, finely defined categories of employment. Most hospitality employers use sophisticated software packages to avoid their employees shifting into areas where penalties suddenly are required. It is unclear why the Calombaris outlets did not. Even with such software, central wage specification brings about great distortions as certain activities get priced out of the market (especially services on Sundays). In other cases, employers break the law and offer cash in hand to keep costs down.

Calombaris was unlikely to be personally involved in setting the wage intricacies. There are 120 “modern awards” covering the industry and a business with hundreds of employees would mean thousands of different skills, hours and time schedule permutations. Even so, it is reasonable that the Calombaris business (just like the successful Madison Avenue ad agencies) should gain advantage from the reputation it has built up.

Moreover, lowering the remuneration offered is one way for a firm that offers special benefits to whittle down the applicant list and, perhaps, ensure the applicants are especially keen to pursue excellence. Calombaris’s role in seeking to address the high level of penalty rates was one reason he has been subject to much more obloquy than the ABC and others for underpaying. But the issue is one that derives from Australia’s centralised and detailed determination of wages and rarely arises in other countries.

Australia suffers from the inflexibility of the hospitality sector that central specification of wage levels brings about to an industry tightly attached to changing consumer preferences. It is already under pressure from the loss of thousands of Chinese customers as students and tourists, and faces a disaster unless its regulatory employment conditions are liberalised.

Alan Moran is with Regulation Economics.

George Calombaris is a victim of the Australian regulatory state. The failure of his restaurant businesses has been greeted by a mixture of schadenfreude that a tall poppy has been exposed for having cheated his employees, and tut-tutting for not being sufficiently alive to the regimen under which his industry’s labour hire regulations operate.